Evaluation of the Impact of National HIV Testing Day — United States, 2011–2014

Weekly / June 24, 2016 / 65(24);613–618

Shirley Lee Lecher, MD1; NaTasha Hollis, PhD1; Christopher Lehmann, MD1; Karen W. Hoover, MD1; Avatar Jones1; Lisa Belcher, PhD1 (View author affiliations)

View suggested citationSummary

What is already known about this topic?

For approximately 2 decades, June 27th has been designated as National human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) Testing Day (NHTD) to promote HIV testing and increase awareness of the importance of getting tested for HIV.

What is added by this report?

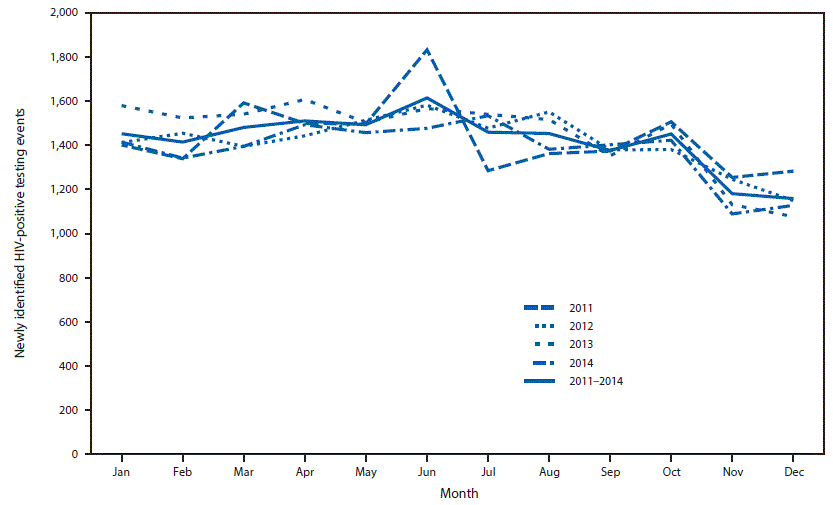

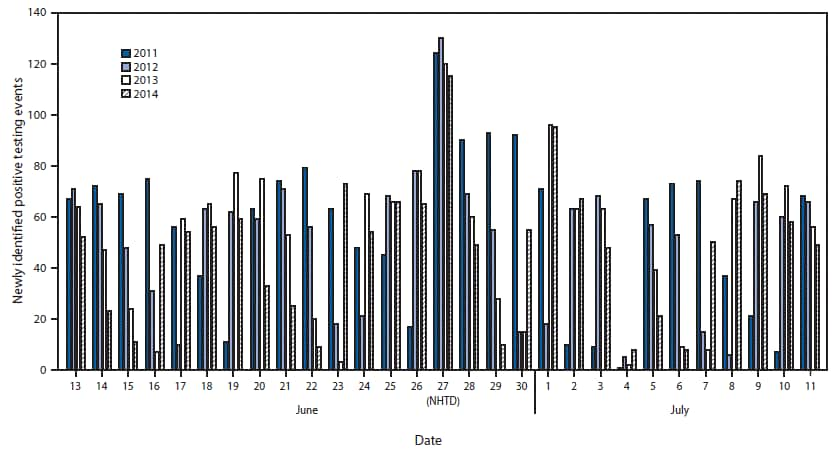

During 2011–2014, there were more CDC-funded HIV testing events and newly identified HIV infections during the month of June compared with the mean for all other months, with significant differences for those most affected by HIV, such as African American (black) men and men who have sex with men (MSM). Compared with the 2 weeks before and after NHTD, the highest number of newly identified HIV positive persons occurred on June 27th each year.

What are the implications for public health practice?

NHTD is an important event to help achieve the National HIV/AIDS Strategy to increase the percentage of persons living with HIV who are aware of their status. NHTD is effective in identifying new HIV-positive diagnoses and identifies persons at highest risk for HIV infection, including black men and MSM.

Altmetric:

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) testing is the first step in the continuum of HIV prevention, care, and treatment services, without which, gaps in HIV diagnosis cannot be addressed. National HIV testing campaigns are useful for promoting HIV testing among large numbers of persons. However, the impact of such campaigns on identification of new HIV-positive diagnoses is unclear. To assess whether National HIV Testing Day (NHTD, June 27) was effective in identifying new HIV-positive diagnoses, National HIV Prevention Program Monitoring and Evaluation (NHM&E) data for CDC-funded testing events conducted during 2011–2014 were analyzed. The number of HIV testing events and new HIV-positive diagnoses during June of each year were compared with those in other months by demographics and target populations. The number of HIV testing events and new HIV-positive diagnoses were also compared for each day leading up to and after NHTD in June and July of each year. New HIV-positive diagnoses peaked in June relative to other months and specifically on NHTD. During 2011–2014, NHTD had a substantial impact on increasing the number of persons who knew their HIV status and in diagnosing new HIV infections. NHTD also proved effective in reaching persons at high risk disproportionately affected by HIV, including African American (black) men, men who have sex with men (MSM), and transgender persons. Promoting NHTD can successfully increase the number of new HIV-positive diagnoses, including HIV infections among target populations at high risk for HIV infection.

After two decades of campaigns promoting the annual NHTD, it is important to know whether these efforts have resulted in an increase in the number of new HIV diagnoses and whether persons at highest risk for HIV infection are effectively reached. NHTD includes approximately 400 events across the United States, spanning several days. The primary goal is to promote HIV testing, an essential step in the diagnosis of HIV, linkage to antiretroviral therapy, and prevention of new infections (1,2). This goal aligns with the National HIV/AIDS Strategy focused on reducing HIV infections, optimizing health outcomes, and decreasing disparities (3). Among persons disproportionately affected, blacks account for approximately half of all newly identified HIV-positive persons, and gay, bisexual, and other MSM are more severely affected by HIV than any other group (4–6). In 2010, HIV testing during the week of NHTD indicated both an increase in CDC-funded HIV testing events and new HIV diagnoses compared with 2 control weeks (7).

To evaluate whether NHTD campaigns have been successful at increasing the number of persons who know their HIV status, test-level data from the NHM&E data system were extracted and analyzed for the years 2011–2014. Data submitted by 55 grantees in 2011, 59 in 2012, 61 in 2013, and 60 in 2014 from CDC-funded jurisdictions in the United States, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands were included. Analysis of valid HIV testing event data was conducted. A valid HIV testing event was defined as an event in which either HIV test technology or an HIV test result was reported. A single testing event included one test (i.e., a single rapid test or single conventional test) or more tests (i.e., single rapid test followed by a single conventional test) conducted to determine a person’s HIV status. An HIV-positive testing event for a person who was not reported previously as testing positive for HIV was categorized as a newly identified HIV infection. The number of HIV testing events conducted during the month of June was compared with the number of HIV testing events conducted during all remaining months of the year (i.e., January–May and July–December). A chi-square test was used to detect differences between the number of HIV testing events conducted in June and the average number of HIV testing events conducted during the remainder of the year. A p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. The differences in the number of testing events and newly identified HIV infections were analyzed by selected demographic characteristics, including age, sex, gender, sexual orientation, race/ethnicity, and risk behaviors. The number of newly identified HIV-positive persons identified each day during the 2 weeks before and after June 27th were compared to determine whether there was an increase on NHTD and to examine testing trends leading up to and after NHTD.

A total of 13,051,035 CDC-funded HIV testing events were conducted during 2011–2014, including 3,299,690 (2011); 3,287,024 (2012); 3,343,633 (2013); and 3,120,688 (2014). The numbers of new HIV-positive test results were 17,216 (0.52%) for 2011; 16,976 (0.52%) for 2012; 17,426 (0.52%) for 2013; and 16,530 (0.53%) for 2014. The number of testing events peaked in June compared with the mean during January–May and July–December for each year during 2011–2014, and the mean number of newly identified HIV-positive persons increased significantly during June (p<0.001) compared with January–May and July–December (Figure 1). When the number of new HIV infections diagnosed each day during the 2 weeks before and after NHTD was compared with new HIV infections diagnosed on June 27, the annual national testing event identified the largest number of new HIV infections compared with any of the other days (Figure 2). New HIV infections identified on NHTD, compared with those identified on the next highest day, increased 25% in 2011, 40% in 2012, 20% in 2013, and 17% in 2014 (Figure 2). The increase in total HIV testing events and the number of newly identified HIV infections was significant for persons aged ≥20 years; for all sex and gender groups (male, female, and transgender); MSM and heterosexuals; and white, black and Hispanic/Latino racial/ethnic groups (Table). MSM identified as white, black, or Hispanic/Latino experienced a significant increase in testing events and newly identified HIV-positive persons in June (Table).

Discussion

National HIV Testing Day (NHTD) effectively targets groups disproportionately affected by HIV. During 2011–2014, there was a significant increase in total testing events as well as newly identified HIV-positive persons in June compared with other months, with a peak in new HIV diagnoses on NHTD. This increase was seen across gender groups, persons aged ≥20 years, and all major racial/ethnic groups. A higher number of testing events and newly identified positive HIV diagnoses occurred among MSM, irrespective of race/ethnicity, and among transgender persons in June compared with the mean during all other months.

Testing is the first link in the chain to provide treatment and disrupt transmission, because persons who are aware that they have HIV infection are less likely to transmit HIV (8,9). Promoting NHTD is an effective strategy to increase HIV testing and thereby, the number of persons who are aware of their HIV status. Because blacks are less likely to have their infection diagnosed and have higher HIV-related mortality rates than other racial/ethnic groups in the United States, it is important to design interventions that specifically target HIV testing for this population (4). NHTD campaigns are usually scheduled by state and local health departments, pharmacies, and HIV community-based organizations in June, leading up to NHTD. These findings indicate persons at highest risk for HIV by age, sex, racial/ethnic group, and target population are effectively reached by mass testing campaigns.

The findings in this report are subject to at least three limitations. First, these analyses included only CDC-funded HIV tests. Therefore, HIV tests supported by other funding sources were not included. Second, the month of June also includes a substantial number of community-based testing events associated with gay pride celebrations in large U.S. cities. It is difficult to know how this might have contributed to an increase in HIV testing and new diagnoses observed during this month. However, a peak in HIV testing and new HIV diagnosis was observed on NHTD compared with all other days. Finally, this study shows increased HIV testing with NHTD; however, receipt of individual test results was not examined. Hence, the magnitude of awareness of individual HIV status cannot be determined from the study.

As a public health strategy consistent with the National HIV/AIDS Strategy, NHTD identifies a number of new HIV infections in populations disproportionately affected by HIV and might increase awareness of HIV status among HIV-infected persons. NHTD might be used strategically in future efforts to increase testing in areas with the highest incidence of HIV. These findings suggest that community-level approaches to advocate early detection and treatment of HIV infection might use mass testing events such as those promoted for NHTD in areas where HIV is most prevalent.

Corresponding author: NaTasha Hollis, nhollis@cdc.gov, 404-718-8636.

1Division of HIV/AIDS Prevention, National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention, CDC.

References

- CDC. National HIV testing day and new testing recommendations. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2014;63:537. PubMedexternal icon

- CDC. National HIV testing day—June 27, 2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2012;61:441. PubMedexternal icon

- Office of National AIDS Policy. National HIV/AIDS strategy for the United States. Washington, DC: Office of National AIDS Policy; 2010. http://www.aids.gov/federal-resources/national-hiv-aids-strategy/nhas.pdfpdf iconexternal icon

- Siddiqi AE, Hu X, Hall HI. Mortality among blacks or African Americans with HIV infection—United States, 2008–2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2015;64:81–6. PubMedexternal icon

- CDC. Estimated HIV incidence among adults and adolescents in the United States, 2007–2010. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC; 2012. http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/statistics_hssr_vol_17_no_4.pdfpdf icon

- Seth P, Walker T, Hollis N, Figueroa A, Belcher L. HIV testing and service delivery among blacks or African Americans—61 health department jurisdictions, United States, 2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2015;64:87–90. PubMedexternal icon

- Van Handel M, Mulatu MS. Effectiveness of the US national HIV testing day campaigns in promoting HIV testing: evidence from CDC-funded HIV testing sites, 2010. Public Health Rep 2014;129:446–54. PubMedexternal icon

- Marks G, Crepaz N, Janssen RS. Estimating sexual transmission of HIV from persons aware and unaware that they are infected with the virus in the USA. AIDS 2006;20:1447–50. CrossRefexternal icon PubMedexternal icon

- Hall HI, Holtgrave DR, Maulsby C. HIV transmission rates from persons living with HIV who are aware and unaware of their infection. AIDS 2012;26:893–6. CrossRefexternal icon PubMedexternal icon

FIGURE 1. Newly identified HIV infections, by month — CDC-funded HIV testing sites, 2011–2014

FIGURE 1. Newly identified HIV infections, by month — CDC-funded HIV testing sites, 2011–2014

Abbreviation: HIV = human immunodeficiency virus.

FIGURE 2. Newly identified HIV infections during the 2 weeks before and after National HIV Testing Day (NHTD, June 27), by date — CDC-funded HIV testing sites, 2011–2014

FIGURE 2. Newly identified HIV infections during the 2 weeks before and after National HIV Testing Day (NHTD, June 27), by date — CDC-funded HIV testing sites, 2011–2014

Abbreviation: HIV = human immunodeficiency virus.

TABLE. Number of HIV testing events and HIV positivity for selected characteristics conducted by health departments providing test-level data in the United States, Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands, 2011–2014

TABLE. Number of HIV testing events and HIV positivity for selected characteristics conducted by health departments providing test-level data in the United States, Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands, 2011–2014

| Characteristic | Total HIV testing events, 2011–2014 | Newly identified HIV infections, 2011–2014 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| June (total) | 11 mos (mean)* | p-value | June (total) | 11 mos (mean)* | p-value | |

| Age group (yrs) | ||||||

| <13 | 2,225 | 2,058 | 0.011 | 7 | 7 | 0.942 |

| 13–19 | 100,297 | 96,689 | <0.001 | 212 | 193 | 0.343 |

| 20–29 | 473,562 | 439,494 | <0.001 | 2,469 | 2,239 | 0.001 |

| 30–39 | 267,331 | 239,610 | <0.001 | 1,486 | 1,341 | 0.006 |

| 40–49 | 173,300 | 150,241 | <0.001 | 1,265 | 1,012 | <0.001 |

| ≥50 | 173,506 | 141,857 | <0.001 | 982 | 766 | <0.001 |

| Invalid/Missing† | 7,498 | 7,626 | — | 34 | 51 | — |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 583,786 | 525,661 | <0.001 | 5,141 | 4,454 | <0.001 |

| Female | 604,552 | 543,579 | <0.001 | 1,177 | 1,063 | 0.016 |

| Transgender | 4,343 | 3,284 | <0.001 | 103 | 69 | 0.010 |

| Invalid/Missing§ | 5,038 | 5,050 | — | 34 | 23 | — |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||||

| White | 318,557 | 292,036 | <0.001 | 1,309 | 1,159 | 0.003 |

| Black | 538,850 | 476,566 | <0.001 | 3,404 | 2,964 | <0.001 |

| Hispanic | 257,342 | 229,503 | <0.001 | 1,361 | 1,167 | <0.001 |

| Other¶ | 40,428 | 36,468 | <0.001 | 201 | 170 | 0.105 |

| Invalid/Missing** | 42,542 | 43,001 | — | 180 | 148 | — |

| Target population†† | ||||||

| Male-to-male sexual contact and injection drug use | 2,782 | 2,564 | 0.003 | 112 | 97 | 0.287 |

| Male-to-male sexual contact | 97,890 | 79,991 | <0.001 | 2,720 | 2,420 | <0.001 |

| Transgender and injection drug use | 187 | 164 | 0.214 | 6 | 5 | 0.676 |

| Transgender | 4,156 | 3,121 | <0.001 | 97 | 65 | 0.011 |

| Injection drug use | 28,604 | 25,879 | <0.001 | 133 | 122 | 0.498 |

| Heterosexual | 537,641 | 485,172 | <0.001 | 1,767 | 1,551 | <0.001 |

| Male-to-male sexual contact by race/ethnicity | ||||||

| White, non-Hispanic | 43,512 | 35,985 | <0.001 | 803 | 662 | <0.001 |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 24,540 | 19,998 | <0.001 | 1,196 | 1,102 | 0.049 |

| Hispanic | 23,617 | 19,065 | <0.001 | 681 | 605 | 0.034 |

| Total | 1,197,719 | 1,077,574 | <0.001 | 6,455 | 5,608 | <0.001 |

Abbreviation: HIV = human immunodeficiency virus.

* The sum of the average during January–May and July–December over 3 years (2011–2014).

† Includes invalid and/or missing values that are needed to determine age.

§ Includes other specified, declined/not asked, or invalid/missing.

¶ Includes multirace, Asian, American Indian, Alaskan Native, Native Hawaiian, or Pacific Islander.

** Includes declined, don’t know/not asked, invalid/missing.

†† Data to identify target populations are required for all testing events conducted in non-health care settings and only HIV-positive testing events in health care settings.

Suggested citation for this article: Lecher SL, Hollis N, Lehmann C, Hoover KW, Jones A, Belcher L. Evaluation of the Impact of National HIV Testing Day — United States, 2011–2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2016;65:613–618. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6524a2external icon.

MMWR and Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report are service marks of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Use of trade names and commercial sources is for identification only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Department of

Health and Human Services.

References to non-CDC sites on the Internet are

provided as a service to MMWR readers and do not constitute or imply

endorsement of these organizations or their programs by CDC or the U.S.

Department of Health and Human Services. CDC is not responsible for the content

of pages found at these sites. URL addresses listed in MMWR were current as of

the date of publication.

All HTML versions of MMWR articles are generated from final proofs through an automated process. This conversion might result in character translation or format errors in the HTML version. Users are referred to the electronic PDF version (https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr) and/or the original MMWR paper copy for printable versions of official text, figures, and tables.

Questions or messages regarding errors in formatting should be addressed to mmwrq@cdc.gov.