|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

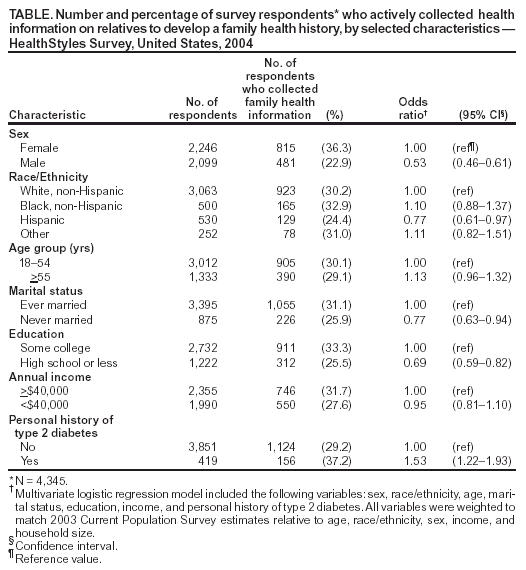

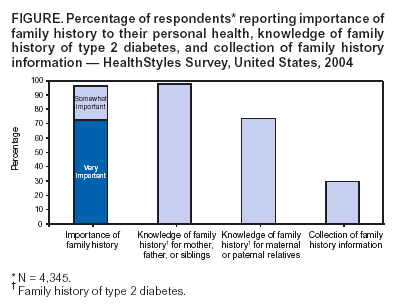

Persons using assistive technology might not be able to fully access information in this file. For assistance, please send e-mail to: mmwrq@cdc.gov. Type 508 Accommodation and the title of the report in the subject line of e-mail. Awareness of Family Health History as a Risk Factor for Disease --- United States, 2004Persons who have close relatives with certain diseases (e.g., heart disease, diabetes, and osteoporosis) are more likely to develop those diseases themselves (1). Family health history is an important risk factor that reflects inherited genetic susceptibility, shared environment, and common behaviors. Although clinicians are trained to collect family histories, substantial barriers exist to obtaining this information in primary care practice (e.g., lack of time or lack of reimbursement) (2). To promote the use of family history as a screening tool for disease prevention and health promotion, several initiatives have called for new self-administered family history collection tools and educational programs to help clinicians interpret and apply family history information to patient care (3,4). To assess attitudes, knowledge, and practices of U.S. residents regarding their family health histories, CDC analyzed data from the 2004 HealthStyles Survey. This report summarizes the results of that analysis, which indicated that although 96.3% of survey respondents believe their family history is important for their own health, few have actively collected health information from their relatives to develop a family history. Targeted public health efforts are needed to 1) help persons collect family history information to share with their health-care providers and 2) educate and assist providers to interpret and apply this information effectively. HealthStyles is an annual mail survey of the U.S. population aged >18 years that examines health-related attitudes and behaviors (5). The survey is designed and conducted by Porter Novelli (Washington, DC), with technical assistance from health organizations, including CDC. In July and August 2004, a stratified random sample of 6,175 respondents was selected from approximately 600,000 households previously recruited to participate in a consumer marketing survey. In return for their participation, respondents were given small gifts (e.g., a 20-minute calling card) and entered into a sweepstakes drawing. Of the 6,175 households contacted by mail, 4,345 (70.4%) returned the survey. Survey data were weighted to match the 2003 Current Population Survey estimates relative to age, race/ethnicity, sex, income, and household size. The survey included the following two general questions related to family history: 1) "How important do you think knowledge of your family's health history is to your personal health?" (possible responses were "very important," "somewhat important," "not at all important," or "not sure") and 2) "Have you ever actively collected heath information from your relatives for purposes of developing a family health history?" The likelihood of collecting a family health history was evaluated in relation to personal characteristics by using a multivariable logistic regression model. In addition, the 2004 HealthStyles Survey had a special focus on type 2 diabetes, so five questions were included to assess family history of this condition: 1) "Has your mother ever been diagnosed with type 2 diabetes?" 2) "Has your father ever been diagnosed with type 2 diabetes?" 3) "How many of your brothers and sisters were diagnosed with type 2 diabetes?" 4) "How many of your mother's relatives (her sisters, brothers, and parents) were diagnosed with type 2 diabetes?" and 5) "How many of your father's relatives (his sisters, brothers, and parents) were diagnosed with type 2 diabetes?" Knowledge of family history of type 2 diabetes was assessed by comparing "yes" or "no" responses with "don't know" responses. Of the 4,345 respondents, 3,063 (70.5%) were non-Hispanic whites and 3,012 (69.3%) were aged 18--54 years; 2,732 (62.9%) had at least some college education, and 3,395 (78.1%) reported ever being married (Table). Slightly more than half of all respondents were female (2,246; 51.7%) and reported annual incomes >$40,000 (2,355; 54.2%). Almost all of the respondents (4,183; 96.3%) considered knowledge of family history either very important (3,151; 72.5%) or somewhat important (1,032; 23.8%) to their personal health. Women were slightly more likely than men to report that family history was very important to their own health; equal proportions of men and women considered family history somewhat important. Respondents who had a high school education or less or who were aged >55 years were less likely to report that family history was important for their own health. Although the majority of respondents reported that family history was important, substantially fewer persons (1,296; 29.8%) reported actively collecting information to develop a family health history (Figure). Those who had collected a family health history were more likely to be female, previously or currently married, and to have more than a high school education. Respondents with a personal history of type 2 diabetes were also more likely to have collected health information from their relatives (Table). Respondents' knowledge of family history of type 2 diabetes varied by type of relative (Figure). Moreover, more respondents reported knowing the type 2 diabetes status of their siblings (94.5%) and mother (91.2%) than of their father (87.8%; p<0.0001). Similarly, a greater percentage of respondents reported knowing the type 2 diabetes status of maternal relatives (77.0%) than paternal relatives (70.4%; p<0.0001). Non-Hispanic white race/ethnicity and higher education and income levels were positively associated with knowledge of family history of type 2 diabetes. Reported by: PW Yoon, ScD, MT Scheuner, MD, M Gwinn, MD, MJ Khoury, MD, PhD, Office of Genomics and Disease Prevention; C Jorgensen, DrPH, Div of Cancer Prevention and Control, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion; S Hariri, PhD, S Lyn, MD, EIS officers, CDC. Editorial Note:The findings in this report indicate that 96.3% of respondents considered knowledge of family history important to their personal health and that 70.0%--94.5% could report the type 2 diabetes status of their relatives, depending on the type of relative. However, only 29.8% reported actively collecting health information from their relatives to develop a family health history. This suggests that many persons know their family health histories but are not actively collecting the information. The analysis also suggests that certain population characteristics (e.g., sex, race, education, and socioeconomic status) might affect attitudes, knowledge, and practices regarding family health history. The findings of this analysis are subject to at least two limitations. First, the HealthStyles Survey is subject to selection bias because the survey population is not a randomly drawn sample of the U.S. population. The results from this survey should be compared with data from population-based surveys, such as the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System survey (6). Second, the assessment of awareness of disease status among relatives was limited to type 2 diabetes. Family history of other common diseases (e.g., cardiovascular diseases and cancer) should be assessed. Most diseases are the result of complex interactions between genetic and environmental factors (7). Family health history reflects these interactions and helps predict risk for certain disorders, including birth defects, asthma, cardiovascular disease, cancer, diabetes, depression, Alzheimer's disease, and osteoporosis (1,8) For example, an evaluation of the risk for coronary heart disease (CHD) using a high school--based family history project determined that family history of CHD and stroke was identified in only 14% and 11% of families, respectively; however, these families accounted for 72% of all early-onset CHD and 86% of early stroke events (9). Although family history can identify persons at increased risk for disease, its potential as a screening tool has not been realized in clinical and public health practice (2). An observational study of primary care physicians indicated that family histories were discussed about half the time at new visits and 22% of the time during follow-up visits (10). The average duration of the family history discussion was 2.5 minutes and focused more often on psychosocial concerns than on other health matters. To improve the use of family history in the clinical setting, the barriers to providers' collection and interpretation of a family history must be addressed. The Department of Health and Human Services is highlighting the importance of family history for disease prevention with the U.S. Surgeon General's Family History Initiative. This initiative has proposed that Thanksgiving Day be designated a National Family History Day in which persons collect their family health histories. A new web-based tool, My Family Health Portrait (http://www.hhs.gov/familyhistory), enables persons to collect family history for six diseases (CHD, stroke, diabetes, and colorectal, breast, and ovarian cancer) and identify additional diseases that occur in their families. After the family history information is completed, a report is generated that includes a pedigree drawing, a listing of the family history data entered, and a statement about the importance of sharing the history with their health-care providers. My Family Health Portrait is based on a self-administered tool being developed by CDC that will enable collection of family health history and provide recommendations tailored to the level of familial risk. In 2005, the CDC tool will be evaluated in clinical settings. Information about the tool can be found at http://www.cdc.gov/genomics/activities/ogdp/2003/chap06.htm. Although national efforts have begun to promote the collection and use of family history information, the HealthStyles Survey data presented in this report suggest that certain subgroups of the population might benefit from targeted programs to raise awareness about the collection and recording of family health histories. References

Table  Return to top. Figure  Return to top.

Disclaimer All MMWR HTML versions of articles are electronic conversions from ASCII text into HTML. This conversion may have resulted in character translation or format errors in the HTML version. Users should not rely on this HTML document, but are referred to the electronic PDF version and/or the original MMWR paper copy for the official text, figures, and tables. An original paper copy of this issue can be obtained from the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office (GPO), Washington, DC 20402-9371; telephone: (202) 512-1800. Contact GPO for current prices. **Questions or messages regarding errors in formatting should be addressed to mmwrq@cdc.gov.Page converted: 11/10/2004 |

|||||||||

This page last reviewed 11/10/2004

|