For Healthcare Providers

Clinical features

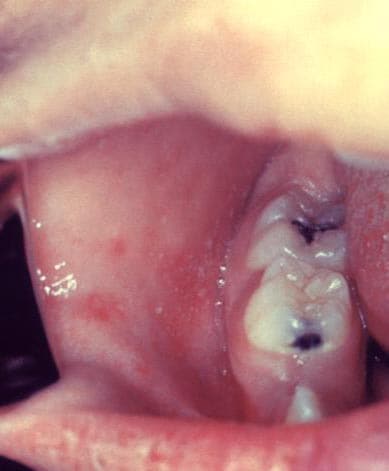

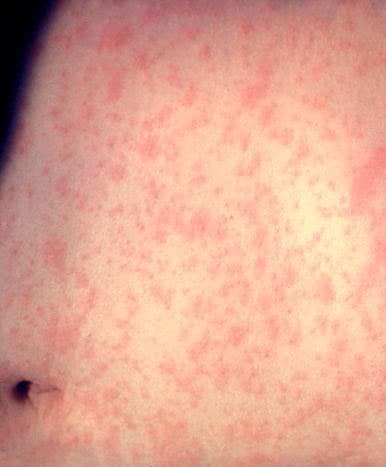

Measles is an acute viral respiratory illness. It is characterized by a prodrome of fever (as high as 105°F) and malaise, cough, coryza, and conjunctivitis -the three “C”s -, a pathognomonic enanthema (Koplik spots) followed by a maculopapular rash. The rash usually appears about 14 days after a person is exposed. The rash spreads from the head to the trunk to the lower extremities. Patients are considered to be contagious from 4 days before to 4 days after the rash appears. Of note, sometimes immunocompromised patients do not develop the rash.

Measles Clinical Presentation, Diagnosis, and Prevention COCA Call

Learn more about measles and other causes of febrile rash illness, how to diagnose and report measles, and the MMR vaccine.

Measles Clinical Features and Diagnosis Video

Learn the signs and symptoms of measles for quicker diagnosing and share this resource with health care providers in your community.

The virus

Measles is caused by a single-stranded, enveloped RNA virus with 1 serotype. It is classified as a member of the genus Morbillivirus in the Paramyxoviridae family. Humans are the only natural hosts of measles virus.

Background

In the decade before the live measles vaccine was licensed in 1963, an average of 549,000 measles cases and 495 measles deaths were reported annually in the United States. However, it is likely that, on average, 3 to 4 million people were infected with measles annually; most cases were not reported. Of the reported cases, approximately 48,000 people were hospitalized from measles and 1,000 people developed chronic disability from acute encephalitis caused by measles annually.

In 2000, measles was declared eliminated from the United States. Elimination is defined as the absence of endemic measles virus transmission in a defined geographic area, such as a region or country, for 12 months or longer in the presence of a well-performing surveillance system. However measles cases and outbreaks still occur every year in the United States because measles is still commonly transmitted in many parts of the world, including countries in Europe, the Middle East, Asia, the Americas, and Africa.

Since 2000, when measles was declared eliminated from the U.S., the annual number of cases has ranged from a low of 37 in 2004 to a high of 1,282 in 2019. The majority of cases in the United States have been among people who are not vaccinated against measles. Measles cases occur as a result of importations by people who were infected while in other countries and from subsequent transmission that may occur from those importations. Measles is more likely to spread and cause outbreaks in communities where groups of people are unvaccinated.

It is critical for all international travelers to be protected against measles, regardless of their destination.

Outbreaks in countries to which Americans often travel can directly contribute to an increase in measles cases in the United States. In recent years, measles importations have come from frequently visited countries, including, but not limited to, the Philippines, Ukraine, Israel, Thailand, Vietnam, England, France, Germany, and India, where large outbreaks were reported.

For additional information on where measles outbreaks are occurring globally, visit: Global Measles Outbreaks (cdc.gov)

Complications

Common complications from measles include otitis media, bronchopneumonia, laryngotracheobronchitis, and diarrhea.

Even in previously healthy children, measles can cause serious illness requiring hospitalization.

- One out of every 1,000 measles cases will develop acute encephalitis, which often results in permanent brain damage.

- One to three out of every 1,000 children who become infected with measles will die from respiratory and neurologic complications.

- Subacute sclerosing panencephalitis (SSPE) is a rare, but fatal degenerative disease of the central nervous system characterized by behavioral and intellectual deterioration and seizures that generally develop 7 to 10 years after measles infection.

People at high risk for complications

People at high risk for severe illness and complications from measles include:

- Infants and children aged <5 years

- Adults aged >20 years

- Pregnant women

- People with compromised immune systems, such as from leukemia and HIV infection

Transmission

Measles is one of the most contagious of all infectious diseases; up to 9 out of 10 susceptible persons with close contact to a measles patient will develop measles. The virus is transmitted by direct contact with infectious droplets or by airborne spread when an infected person breathes, coughs, or sneezes. Measles virus can remain infectious in the air for up to two hours after an infected person leaves an area.

Diagnosis and laboratory testing

Healthcare providers should consider measles in patients presenting with febrile rash illness and clinically compatible measles symptoms, especially if the person recently traveled internationally or was exposed to a person with febrile rash illness. Healthcare providers are required to report suspected measles cases to their local health department.

Laboratory confirmation is essential for all sporadic measles cases and all outbreaks. Detection of measles-specific IgM antibody in serum and measles RNA by real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) in a respiratory specimen are the most common methods for confirming measles infection. Healthcare providers should obtain both a serum sample and a throat swab (or nasopharyngeal swab) from patients suspected to have measles at first contact with them. Urine samples may also contain virus, and when feasible to do so, collecting both respiratory and urine samples can increase the likelihood of detecting measles virus.

Molecular analysis can also be conducted to determine the genotype of the measles virus. Genotyping is used to map the transmission pathways of measles viruses. The genetic data can help to link or unlink cases and can suggest a source for imported cases. Genotyping is the only way to distinguish between wild-type measles virus infection and a rash caused by a recent measles vaccination.

For more information, see Measles Lab Tools.

Evidence of immunity

Acceptable presumptive evidence of immunity against measles includes at least one of the following:

- written documentation of adequate vaccination:

- one or more doses of a measles-containing vaccine administered on or after the first birthday for preschool-age children and adults not at high risk

- two doses of measles-containing vaccine for school-age children and adults at high risk, including college students, healthcare personnel, and international travelers

- laboratory evidence of immunity*

- laboratory confirmation of measles

- birth before 1957

Healthcare providers and health departments should not accept verbal reports of vaccination without written documentation as presumptive evidence of immunity. For additional details about evidence of immunity criteria, see Table 3 in Prevention of Measles, Rubella, Congenital Rubella Syndrome, and Mumps, 2013: Summary Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP).

Vaccination

Measles can be prevented with measles-containing vaccine, which is primarily administered as the combination measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) vaccine. The combination measles-mumps-rubella-varicella (MMRV) vaccine can be used for children aged 12 months through 12 years for protection against measles, mumps, rubella and varicella. Single-antigen measles vaccine is not available.

One dose of MMR vaccine is approximately 93% effective at preventing measles; two doses are approximately 97% effective. Almost everyone who does not respond to the measles component of the first dose of MMR vaccine at age 12 months or older will respond to the second dose. Therefore, the second dose of MMR is administered to address primary vaccine failure [1]

Vaccine recommendations

Children

CDC recommends routine childhood immunization for MMR vaccine starting with the first dose at 12 through 15 months of age, and the second dose at 4 through 6 years of age or at least 28 days following the first dose. The measles-mumps-rubella-varicella (MMRV) vaccine is also available to children 12 months through 12 years of age; the minimum interval between doses is three months.

Students at post-high school educational institutions

Students at post-high school educational institutions without evidence of measles immunity need two doses of MMR vaccine, with the second dose administered no earlier than 28 days after the first dose.

Adults

People who are born during or after 1957 who do not have evidence of immunity against measles should get at least one dose of MMR vaccine.

International travelers

People 6 months of age or older who will be traveling internationally should be protected against measles. Before traveling internationally,

- Infants 6 through 11 months of age should receive one dose of MMR vaccine†

- Children 12 months of age or older should have documentation of two doses of MMR vaccine (the first dose of MMR vaccine should be administered at age 12 months or older; the second dose no earlier than 28 days after the first dose)*

- Teenagers and adults born during or after 1957 without evidence of immunity against measles should have documentation of two doses of MMR vaccine, with the second dose administered no earlier than 28 days after the first dose

† Infants who get one dose of MMR vaccine before their first birthday should get two more doses according to the routinely recommended schedule (one dose at 12 through 15 months of age and another dose at 4 through 6 years of age or at least 28 days later).

* The measles-mumps-rubella-varicella (MMRV) vaccine is also available to children 12 months through 12 years of age. If used in place of MMR vaccine, the first dose should be administered at age 12 months or older, and the second dose no earlier than three months after the first dose. MMRV should not be administered to anyone older than 12 years of age.

Healthcare personnel

Healthcare personnel should have documented evidence of immunity against measles, according to the recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices [48 pages].

For more information, see measles vaccination recommendations.

Some people should not get MMR or MMRV vaccine. For information about contraindications, see who should NOT get vaccinated with MMR or MMRV vaccine?

Footnote

- CDC. Prevention of Measles, Rubella, Congenital Rubella Syndrome, and Mumps, 2013: Summary Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR 2013;62(RR04);1-34.

Post-exposure prophylaxis

People exposed to measles who cannot readily show that they have evidence of immunity against measles should be offered post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP). To potentially provide protection or modify the clinical course of disease among susceptible persons, either administer MMR vaccine within 72 hours of initial measles exposure, or immunoglobulin (IG) within six days of exposure. Do not administer MMR vaccine and IG simultaneously, as this practice invalidates the vaccine.

Please refer to the following references for additional information on post-exposure prophylaxis:

- Prevention of Measles, Rubella, Congenital Rubella Syndrome, and Mumps, 2013: Summary Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). June 14, 2013.

- General Recommendations on Immunization: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). January 28, 2011

Footnote

- Siegel JD, Rhinehart E, Jackson M, Chiarello L, and the Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee, 2007 Guidelines for Isolation Precautions: Preventing Transmission of Infectious Agents in Healthcare Settings.

Isolation

Infected people should be isolated for four days after they develop a rash; airborne precautions should be followed in healthcare settings. Because of the possibility, albeit low, of MMR vaccine failure in healthcare providers exposed to infected patients, they should all observe airborne precautions in caring for patients with measles. The preferred placement for patients who require airborne precautions is in a single-patient airborne infection isolation room (AIIR). Regardless of presumptive immunity status, all healthcare staff entering the room should use respiratory protection consistent with airborne infection control precautions (use of an N95 respirator or a respirator with similar effectiveness in preventing airborne transmission).

For more information, visit Interim Guidance on Infection Prevention and Control Recommendations for Measles in Healthcare settings.

Treatment

There is no specific antiviral therapy for measles. Medical care is supportive and to help relieve symptoms and address complications such as bacterial infections.

Severe measles cases among children, such as those who are hospitalized, should be treated with vitamin A. Vitamin A should be administered immediately on diagnosis and repeated the next day. The recommended age-specific daily doses are

- 50,000 IU for infants younger than 6 months of age

- 100,000 IU for infants 6–11 months of age

- 200,000 IU for children 12 months of age and older

For more information, see page 351 of the World Health Organization measles and vitamin A guidance [12 pages]. Also see Red Book Online: Measles.

Photos

Resources

- Most Measles Cases in 25 Years: Is This the End of Measles Elimination in the United States?

COCA call/Webinar presented May 21, 2019 - Provider Resources for Vaccine Conversations with Parents

- An Introduction to Measles Powerpoint presentation [20 pages]

- Measles Data and Statistics Powerpoint presentation [15 pages]