Monthy Case Studies - 2000

Case #35 - May, 2000

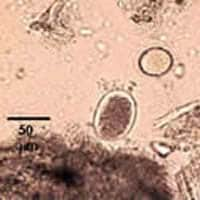

A parasitologist from CDC was assigned to a primate research facility in Kenya to teach a course entitled "An Introduction to Laboratory Methods for the Diagnosis of Parasitic Diseases." Ten staff members at the research facility volunteered to collect stool specimens for demonstration purposes in the class. Their specimens were preserved in 10% formalin and used to demonstrate the formalin-ethyl acetate concentration procedure. None of the staff members had health complaints at the time of collection. The following images show what was seen in one of the specimens (Figures A through H). What is your diagnosis? Based on what criteria?

Figure A

Figure B

Figure C

Figure D

Figure E

Figure F

Figure G

Figure H

Answer to Case #35

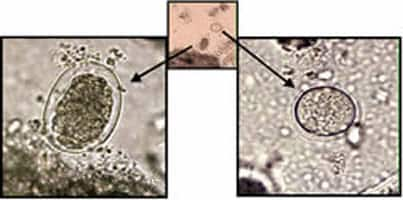

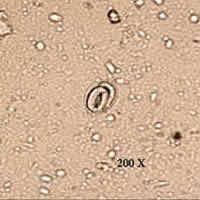

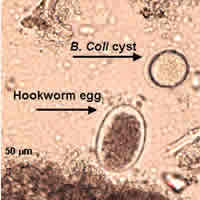

This case demonstrated a mixed infection of hookworm, most-likely caused by Necator americanus based on geographic distribution, and balantidiasis, caused by Balantidium coli. Hookworm eggs are fairly easy to identify from their general appearance, size (55 to 65 micrometers by 36 to 40 micrometers), and thin shells. The embryonated egg (Figure E) may have been tricky since Strongyloides stercoralis eggs, although usually not seen in stool preparations, are similar in appearance. Occasionally, one may see embryonated hookworm eggs if the specimen was kept at room temperature, even for a short period of time, before being preserved in formalin. A mixture of fully embryonated and partially embryonated eggs suggests hookworm infection. If this had been an infection with S. stercoralis, one would expect to see larvae instead of eggs, but, if eggs were present, they would all most likely be fully embryonated. We did not see any nematode larvae in this specimen that might suggest an infection with S. stercoralis. Morphologically, eggs of hookworms and S. stercoralis are difficult to distinguish when embryonated.

The images of the cysts of B. coli (from a wet mount made from the concentrate of this specimen) were difficult to diagnose. Sometimes, especially in older cysts, there is not much morphological detail to be seen other than size (about 50 to 70 micrometers). In the images (Figure C), one can see the cyst wall and cytoplasmic inclusions instead of structures such as nuclei that would normally be seen in ameba cysts. Cysts of B. coli may have some or none of the following diagnostic features: evidence of cilia inside the cyst wall, a large macronucleus, a smaller micronucleus, and cytoplasmic inclusions or vacuoles. We have added arrows to the original images sent in this case to highlight some of these features.

Figure A

More on: Hookworm

More on: Balantidiasis

Images presented in the monthly case studies are from specimens submitted for diagnosis or archiving. On rare occasions, clinical histories given may be partly fictitious.

ShareCompartir

ShareCompartir