Alcohol Screening and Brief Intervention For People Who Consume Alcohol and Use Opioids

ARCHIVED WEBPAGE: This web page is archived for historical purposes and is no longer being updated.

Healthcare providers can use alcohol screening and brief intervention (ASBI) before prescribing opioids to reduce opioid overdose deaths involving alcohol

- Why is it important to administer a screening and brief intervention for reducing alcohol use before prescribing opioids?

- What is ASBI?

- How can healthcare providers integrate ASBI into their practices?

- What are the recommended methods to screen for excessive alcohol use?

- Why is it important to screen for more than just severe alcohol use disorders?

- What tools are available to assist healthcare professionals?

Alcohol was involved in 22% of deaths caused by prescription opioids and 18% of emergency department visits related to the misuse of prescription opioids in the United States in 2010.1 Screening and brief intervention for excessive alcohol use (ASBI) is an effective clinical prevention strategy for reducing excessive drinking, but it is underused in clinical settings. The purpose of this document is to familiarize health departments and healthcare providers with ASBI, discuss its usefulness for helping people who drink excessively who may be prescribed an opioid to drink less or stop drinking altogether while using opioid medications, and assist state health departments in supporting health systems and other community partners carrying out ASBI in various settings as a part of routine practice. A reference for routinely implementing ASBI in health systems is also included.

Why is it important to administer a screening and brief intervention for reducing alcohol use before prescribing opioids?

- People who drink excessively who use prescription opioids are at greater risk of overdose and death due to the depressant effects of alcohol on the respiratory system and central nervous system. The risk of harm increases with the amount of alcohol consumed, but there is no safe level of alcohol use for people using opioids.2,3

Excessive alcohol use includes:

- Binge drinking: consuming 5 or more drinks for men or 4 or more drinks for women, per occasion.

- Heavy drinking: consuming 15 or more drinks per week for men or 8 or more drinks per week for women.

- Any drinking by pregnant women or people younger than the minimum legal drinking age of 21.

According to the 2020–2025 Dietary Guidelines for Americans, adults of legal drinking age can choose not to drink, or to drink in moderation by limiting intake to 2 drinks or less in a day for men and 1 drink or less in a day for women, when alcohol is consumed. Drinking less is better for health than drinking more.4

- The US Food and Drug Administration indicates that healthcare professionals should avoid prescribing opioids to people using central nervous system depressants, including alcohol.3

What is ASBI?

ASBI can be delivered in person via a conversation, which is the traditional method, or electronically.5,6

- Traditional ASBI involves several steps:

- Administering a standardized set of screening questions [PDF-2.12MB] to assess the patient’s drinking patterns.7

- Providing individuals who drink excessively with face-to-face feedback about the risks of this behavior.

- Talking with people who are drinking excessively about changing their drinking behavior, and referring those with a severe alcohol use disorder to specialized treatment.

- Electronic screening and brief intervention (e-SBI) uses electronic devices (e.g., computers, tablets, mobile devices) to deliver at least one key element of the intervention. Components of e-SBI can be

- Delivered in various settings, including healthcare systems, universities, or communities.

- Integrated into standard organizational practices to ensure consistent delivery to intended recipients (e.g., healthcare systems may deliver it to all new patients).

- However, it is important to note that e-SBI tools may have a cost to administer them and require technical support for the devices and programs. E-SBI tools should be evaluated by providers in relation to reading level, language, administration time, and appropriateness for the population receiving the service.

ASBI is an evidence-based strategy for reducing excessive drinking

- The US Preventive Services Task Force “recommends that clinicians screen adults aged 18 years or older for alcohol misuse and provide persons engaged in risky or hazardous drinking with brief behavioral counseling interventions to reduce alcohol misuse.”8

- The Community Preventive Services Task Force “recommends electronic screening and brief intervention based on strong evidence of effectiveness in reducing self-reported excessive alcohol consumption and alcohol-related problems among intervention participants.”6

How can healthcare providers integrate ASBI into their practices to reduce excessive drinking among patients using prescription opioids?

Providers can do the following:

- Routinely screen people who are seeking care for acute or chronic pain for excessive alcohol use using an approved screening method (see the following recommendations).

- Consider collaborating with other health professionals to perform specific components of ASBI. These include in-depth assessment of drinking behavior, brief intervention, or both.

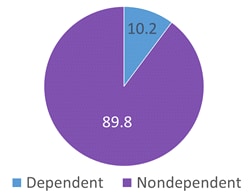

- Identify substance use disorder specialists to refer the small percentage (about 10%) of people who drink excessively with severe alcohol use disorders (see step 5 in CDC’s guide for planning and implementing ASBI [PDF-2.12MB]).7,9

- Consider involving a pain management specialist in the care of acute and chronic pain in people with alcohol use disorders.

ASBI methods may need to be modified for use with people who are using prescription opioids. For example, these patients may need to be advised not to drink at all while using these medications. However, current ASBI techniques still can be used to help people who drink excessively who are prescribed opioids. They can be advised to drink less in order to reduce the risk of dangerous interactions between alcohol and these medications and also be advised that there is no safe level of alcohol consumption when using these medications.

What are the recommended methods to screen for excessive alcohol use?

Option 110

A single-question screener: “How many times in the past year have you had 5 or more drinks in a day (for men) or 4 or more drinks in a day (for women)?”

Option 2 Brief Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT 1-3) (US)7:

- How often do you have a drink containing alcohol?

- How many drinks containing alcohol do you have on a typical day you are drinking?

- How often do you have X (5 for men; 4 for women & for men over age 65) or more drinks on one occasion?

Both of the screening instruments above have been recommended by CDC to assess alcohol consumption, and the practice or setting can choose which one to use. The single-question screener is short, simple to administer, and easy to remember. The AUDIT 1-3 (US), which can also be administered in about a minute, represents the first 3 questions of the full AUDIT (US). The full AUDIT (US) is considered the “gold standard” for alcohol screening instruments. For people who screen positive on the single-question screener or the AUDIT 1-3 (US), follow up with the full AUDIT (US) is needed—or just the remaining 7 questions of the full AUDIT (US) if the AUDIT 1-3 (US) screening is used—to assess if a brief intervention is sufficient, or if a brief intervention and referral to specialized treatment are needed.

Why is it important to screen for more than just severe alcohol use disorders?

About 9 in 10 adult adults who drink excessively in the U.S. do not meet the diagnostic criteria for severe alcohol use disorders (i.e., alcohol dependence) (see figure).9 Therefore, it is important to use screening tools that will identify nondependent people who drink excessively as well.

What tools are available to assist healthcare professionals in carrying out ASBI, informing people of the risks of excessive drinking, and implementing ASBI routinely in their practice settings?

- CDC’s guide for planning and implementing ASBI [PDF-2.13MB]7:

- Designed to help an individual clinician or organization (e.g., primary care practice) put this intervention into practice.

- Describes the single-question screener (Appendix F), the brief Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT 1-3) (US) (Appendix G), and the full AUDIT (Appendix H).

- Discusses how to administer a 5–15 minute brief intervention for people who screen positive for excessive drinking, but do not have a severe alcohol use disorder (Appendices N and O).

CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain

The CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain recommends that clinicians always discuss with patients the danger of using alcohol and prescription opioids at the same time, including the increased risk of respiratory depression (see Recommendation 3). Clinicians should also regularly assess patients’ alcohol use while they’re taking prescription opioids (see Recommendation 8).12

What does the CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain—United States, 2016 suggest that healthcare providers do to help people with substance use disorders?12

- Discuss the increased risk of developing an opioid use disorder and overdose with people who have a substance use disorder, and carefully consider whether the benefits of opioid therapy outweigh the risks for these patients.

- Incorporate strategies to mitigate the risk of dangerous drug interactions into the pain management plan for people with substance use disorders, and consider offering these patients naloxone.

- Closely monitor people with substance use disorders who are prescribed opioids to determine

- Whether opioids continue to meet treatment goals,

- Whether the patient has experienced common or serious adverse events or shows signs of having an opioid use disorder (e.g., difficulty controlling use, work or family problems related to opioid use),

- Whether the benefits of opioids continue to outweigh risks, and

- Whether opioid dosage can be reduced or opioids can be discontinued (see Recommendation 7).

- Discuss the use of prescription opioids with a patient’s substance use disorder treatment provider.

- Consider consulting pain specialists regarding the management of acute and chronic pain in people with substance use disorders.

Learn more about preventing opioid overdoses, alcohol screening and brief intervention and preventing excessive alcohol use.

- Jones CM, Paulozzi LJ, Mack KA. Alcohol involvement in opioid pain reliever and benzodiazepine drug abuse-related emergency department visits and drug-related deaths – United States, 2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63(40):881–885.

- Gudin JA, Mogali S, Jones JD, Comer SD. Risks, management, and monitoring of combination opioid, benzodiazepines, and/or alcohol use. Postgrad Med. 2013;125(4):115–130.

- Food and Drug Administration. FDA Drug Safety Communication: FDA Warns About Serious Risks and Death When Combining Opioid Pain or Cough Medicines with Benzodiazepines; Requires Its Strongest Warning Website. Accessed September 6, 2017.

- US Department of Agriculture and US Department of Health and Human Services. 2020–2050 Dietary Guidelines for Americansexternal icon. 9th ed. Washington, DC: 2020.

- McKnight-Eily LR, Liu Y, Brewer RD, et al. Vital signs: communication between health professionals and their patients about alcohol use — 44 States and the District of Columbia, 2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63:16–22.

- Tansil KA, Esser MB, Sandhu P, et al. Alcohol electronic screening and brief intervention: a community guide systematic review [PDF-492 KB]. Am J Prev Med. 2016;51(5):801–811.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Planning and Implementing Screening and Brief Intervention for Risky Alcohol Use: A Step-by-Step Guide for Primary Care Practices [PDF-2.13MB]. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities; 2014. Accessed September 6, 2017.

- U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Unhealthy Alcohol Use in Adolescents and Adults: Screening and Behavioral Counseling Interventions Website. Accessed August 5, 2022.

- Esser MB, Hedden SL, Kanny D, Brewer RD, Gfroerer JC, Naimi TS. Prevalence of alcohol dependence among U.S. adult drinkers. Prev Chronic Dis. 2014;11:140329.

- Smith PC, Schmidt SM, Allensworth-Davies D, Saitz R. Primary care validation of a single-question alcohol patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(7):783–788.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Alcohol and Public Health Fact Sheets Website. Accessed September 6, 2017.

- Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R. CDC Guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain— United States, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2016;65(1):1–49.