|

|

Volume

7: No. 1, January 2010

SPECIAL TOPIC

The Role of Public Health in Addressing Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Mental Health and Mental Illness

Annelle B. Primm, MD, MPH; Melba J. T. Vasquez, PhD; Robert A. Mays,

PhD, MSW; Doreleena Sammons-Posey, SM; Lela R. McKnight-Eily, PhD; Letitia R. Presley-Cantrell, PhD; Lisa C. McGuire, PhD; Daniel P. Chapman, PhD, MSc; Geraldine S. Perry, DrPH, RD

Suggested citation for this article: Primm AB, Vasquez MJT, Mays RA, Sammons-Posey D, McKnight-Eily LR, Presley-Cantrell LR, et al. The role of public health in addressing racial and ethnic disparities in mental health and mental illness. Prev Chronic Dis 2010;7(1):A20.

http://www.cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2010/

jan/09_0125.htm. Accessed [date].

PEER REVIEWED

Abstract

Racial/ethnic minority populations are underserved in the American mental health care system. Disparity in treatment between whites and African Americans has increased substantially since the 1990s.

Racial/ethnic minorities may be disproportionately affected by limited English proficiency, remote geographic settings, stigma, fragmented services, cost, comorbidity of mental illness and chronic diseases, cultural understanding of health care services, and

incarceration. We present a model that illustrates how social determinants of health, interventions, and outcomes interact to affect mental health and mental illness. Public health approaches to these concerns include preventive strategies and federal agency collaborations that optimize

the resilience of racial/ethnic minorities. We recommend strategies such as enhanced surveillance, research, evidence-based practice, and public policies that set standards for tracking and reducing disparities.

Back to top

Introduction

Racial and ethnic diversity is increasing in the United States; by 2042,

racial/ethnic minorities are expected to surpass non-Hispanic whites as the

majority population in the United States (1). Nevertheless, racial/ethnic minority populations remain underserved in the mental health care system (2). The Surgeon General advocates a public health approach to eliminate disparities in mental health among racial/ethnic minorities (3). The New Freedom Commission

on Mental Health recommends providing access to high-quality and

culturally effective care that includes underserved, remote, and rural areas of the country and recommends that states monitor mental health service disparities through their comprehensive state mental health plans (2).

We describe mental health disparities among racial/ethnic minority populations, such as differences in prevalence rates, diagnoses, access to care, and sources of care. We propose a model that illustrates the relationships between the social determinants of mental health, the necessary public health interventions, and the expected positive outcomes resulting from these interventions in racial/ethnic minority populations. Finally, we offer additional public health recommendations for

consideration.

Back to top

Existing Mental Health Disparities in

Racial/Ethnic Minority Populations

Health disparities are defined as “differences in the overall rate of disease incidence, prevalence, morbidity, mortality, or survival” (4). The Surgeon General’s report on mental health noted that mental health and mental illness are not polar opposites (5). Mental health is the successful performance of mental function, resulting in productive activities, fulfilling relationships, and the ability to adapt to change and adversity. Mental illness refers to mental disorders

characterized by alterations in thinking, mood, or behavior associated with distress or impaired functioning. The evolution and nuances of definitions of mental health and mental illness are discussed in depth elsewhere in this issue of Preventing Chronic Disease (6).

The prevalence of mental illness differs between whites and racial/ethnic minority populations. For example, among American Indian tribes, the lifetime prevalence of any psychiatric disorder is higher (50%-54% for

men, 41%-46% for women) than among the overall US population (44% for men, 38% for

women) (7). The prevalence of any psychiatric disorder in the past 12 months is 15% for African Americans, 9% for Asian Americans, 16% for Hispanics, and 21% for non-Hispanic whites (8).

Although African Americans and Hispanics have a lower risk of lifetime prevalence of mental disorders

than do whites (9), they have a higher risk of persistence (longer course of illness) (10) and disability from mental illness (2). Furthermore, despite similarities in the measured prevalence of mental illnesses, racial/ethnic minority populations are disproportionately represented in vulnerable populations, such as the homeless and incarcerated, whose responses are not typically recorded

for community surveys (3).

Racial/ethnic minorities who meet criteria for a mental disorder diagnosis may be undiagnosed or misdiagnosed. African Americans with an affective disorder are more likely to be diagnosed with schizophrenia than are white patients (11). Similarly, Hispanics are more likely to be diagnosed with affective disorders than are whites, although the difference is attenuated by adjusting for sociodemographic, care setting, and payment characteristics (12). Another issue of concern is the quality

of care received by racial/ethnic minorities (13). African Americans and Hispanics are less likely than whites to receive guideline-based care for depression and anxiety (13), and African Americans are less likely than whites to

be treated with atypical antipsychotic drugs and other newer agents (14).

Racial/ethnic minorities face barriers in accessing mental health care,

particularly cost of care and fragmented services (3). Only 20% of American

Indians report that they access care through the Indian Health Service (3).

Furthermore, limited English proficiency and health literacy pose barriers for

immigrant populations. In a 2007 study, only 8% of Hispanics who

did not speak English, who reported a need for mental health services, received

services. Likewise, of the non-English speaking Asian/Pacific Islander

population who

reported a need for mental health services, only 11% received services (15). Geographic accessibility is another barrier to care (2). People who live in rural areas have less access to mental health services than do their more urban counterparts (16). Even in rural areas where mental health services are available, some populations may not receive culturally appropriate services because of language barriers.

Medical insurance coverage is also a barrier to mental health care access among some racial/ethnic minorities. Sixteen percent of the overall US population is uninsured, compared with 25% of African Americans and 40% of Hispanics (3). Immigrants are 2.7 times more likely to be without health insurance than are US-born residents (17).

White and racial/ethnic minority populations have different sources of care. African Americans are more likely than whites to use emergency services, primary care physicians, and alternative treatments rather than specialists for diagnosis or treatment of mental disorders. African Americans are also overrepresented in inpatient treatment and underrepresented in outpatient treatment (3). A study of Southwest and Northern

Plains tribal members living on or near reservations found that they are

less likely than the overall population to seek help for mental illness (from specialists, other medical providers, or traditional or spiritual healers) (7). Asian Americans are less likely than whites to visit community mental health centers, emergency departments, self-help groups, or a psychiatric clinic in a general hospital (18).

Back to top

A Proposed Model to Overcome Disparities in Mental

Health for Racial/Ethnic Minority Populations

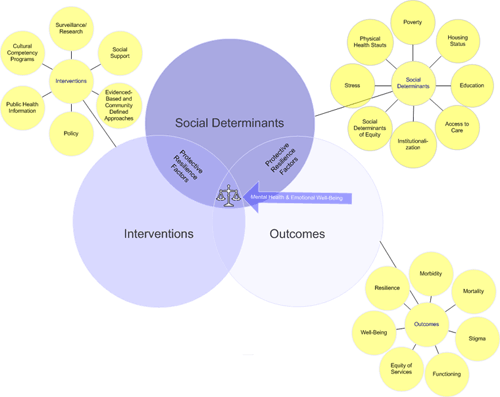

We propose a model in which social determinants, interventions, and outcomes

influence disparities in mental health and mental illness and are in turn subject to influence. The model illustrates the interactions of these factors to promote mental health and prevent mental illness (Figure).

[View

enlarged image

and descriptive text.]

Figure. A proposed model to illustrate the interactions

of social determinants, interventions, and outcomes to promote mental health.

Social determinants

The model’s social determinants are poverty, housing status, education, access to resources, institutionalization, social determinants of equity, stress, and physical health

status. Living in poverty is associated with increased risk for mental, physical, and substance use disorders (19). Racial/ethnic minorities experience low socioeconomic status disproportionately in terms of income, occupation, and education, and this status has been significantly associated with mental illness (3).

Housing status refers to the effects of residential segregation in shaping socioeconomic status. Segregation in housing is associated with social problems such as high unemployment, reduced economic development, concentrated poverty, suboptimal education, and diminished access to health and mental health care (19). Segregated housing units often are substandard and expose occupants to high levels of environmental toxins. The high density of fast-food restaurants and scarcity of markets with

fresh fruits and vegetables in these neighborhoods contribute to poor dietary habits (20). Furthermore, substandard housing and lack of infrastructure in poor urban neighborhoods where many racial/ethnic minority groups live have led to communities that are disenfranchised, with diminished social networks (21).

Racial/ethnic minorities are overrepresented among people who live in poverty,

are homeless, or are institutionalized. Racial/ethnic minorities make up only 26% of the US population (1), but they

make up 57% of the incarcerated population (22). Estimates from interviews with jail inmates in 2002 and with state and federal prisoners in 2004 revealed that more than half of all inmates have a recent history of mental illness (23);

yet only 34% of state prisoners, 24% of federal

prisoners, and 17% of local jail inmates have been treated for mental illness (23).

Social determinants of equity also influence mental health. For example, an intact family provides a strong, protective social network. Protective factors are defined as characteristics or conditions that diminish the likelihood that people will develop mental

illness (5). Religious belief and social support are examples of protective factors. Although not conclusive, some research findings suggest a link between spirituality and well-being, which may operate through

family ties (3). Negative social factors such as racism, racial bias, and discrimination contribute to poor physical and mental health among

racial/ethnic minority populations (24). These populations also experience a

higher rate of other negative life events such as victimization, abuse, and trauma, defined in the figure as stress (3).

The public health system must define disparities in diverse populations, set measurable goals for improvement, focus on community-based research, and acknowledge community needs pertaining to the social determinants of health.

Interventions

Public health interventions are necessary to help prevent mental illness and promote mental health in racial/ethnic minority populations. The interventions depicted in our model

are social support, surveillance/research, cultural competency

programs, public health information, evidence-based and community-defined

approaches, and policy.

Social support from the community, neighborhood, and family decreases

emotional distress and the need for formal treatment (5). These informal

networks can be seen as coping mechanisms that help make mental health programs

successful (5). Current surveillance and research approaches are not adequate to address

mental health disparities in racial/ethnic minority populations, particularly among Asian Americans and American Indians/Alaska Natives. Surveillance and research on these populations should be expanded to provide adequate data to monitor the prevalence, incidence, and severity of mental illness and access to care. These data may lead to the development of culturally based treatments and public health approaches to evaluate their

efficacy (2). Language barriers and ignorance of cultural differences increase the likelihood of misdiagnosis. Including cultural competency programs in clinician training may help, as may encouraging racial/ethnic minorities to enter health care professions.

Furthermore, dissemination of public health information through such techniques

as social marketing could help eliminate the stigma of mental illness among some

racial/ethnic minority groups and in so doing could encourage seeking help for

mental illness. Public health approaches that are defined by the community, that are evidence-based

(25), and that engage racial/ethnic minority populations are necessary to

achieve desired outcomes. Finally, national policies must attempt to improve

mental health among racial/ethnic minority populations through better access to

both mental and physical health care systems (26).

Outcomes

The outcomes in the model are morbidity, mortality, stigma, functioning, equity of services, well-being, and resilience. Higher morbidity and mortality are associated with chronic diseases among mentally ill people in some racial/ethnic minority populations (27,28). For example, among American Indians, a history of trauma, stress, or depression increases the risk for diabetes (29).

The stigma of mental illness among some racial/ethnic minority groups can cause people to avoid seeking specialty mental health care and refuse to receive medication or counseling (3). Such avoidance increases the likelihood of seeking care only at the stage of mental health crisis, when the risk of needing emergency services or involuntary hospitalization is

higher. Other factors, such as lack of insurance, limited health literacy, and cultural beliefs, also interfere with help seeking,

screening, and health assessment.

Positive outcomes include successful mental functioning, equity of services, and well-being, achieved through a combination of protective factors and tailored public health interventions. Resilience, or the capacity to recover from adversity, is often achieved through the positive

effect of protective factors mediating negative social determinants. Resilience can preserve mental health even in the presence of poor socioeconomic circumstances. Religious participation,

volunteerism, and neighborhood collaboration have also been identified as protective factors, strengthening resilience among racial/ethnic minority populations (3).

The intersection of social determinants of health, interventions, and outcomes illustrates how protective factors combined with interventions counterbalance potentially negative social determinants of mental health.

Back to top

Summary and Next Steps

For nearly a decade, federal reports have called for a public health approach that addresses the social determinants of mental illness to eliminate disparities in diagnosis and treatment. A successful approach must consider racial/ethnic minorities in their social contexts because these social determinants influence health outcomes.

As the US population grows increasingly diverse, providers must become more culturally sensitive in the treatment of mental illness. Provider training in the unique barriers to mental health among racial/ethnic minorities may be achieved by mandating such training in medical school and continuing education. Increases in the number of racial/ethnic minority health care providers could also increase the availability of culturally sensitive mental health care. However, the stigma of mental

illness diagnosis and treatment among some groups may delay or prevent mental health care; social marketing campaigns may help alleviate such stigma.

To establish mental health in the public health arena, prevention should be emphasized. An example of universal prevention is the early identification of women with postpartum depression to reduce long-term risks for themselves and their infants (30). The

need to recognize symptoms and provide early screening and treatment for common mental illnesses should be emphasized to racial/ethnic minority populations, the general public, and health care practitioners.

Collaborative efforts to eliminate health disparities are under way among

several federal agencies. One example is the Federal Executive Steering

Committee on Mental Health, an interagency group representing 9 federal

agencies, led by the Department of Health and Human Services. This group was

formed as a result of the New Freedom Commission on Mental Health (2), which

called for a fundamental transformation of the US mental health care

delivery system to one driven by consumer and family needs that focuses on

building resilience, facilitating recovery, and eliminating disparities in mental health services.

Among the steering committee’s initial priorities are chronic disease and

mental illness comorbidities.

We suggest the following strategies to address the disparities in mental health services and prevalence of mental illness in racial/ethnic minority populations:

- Surveillance systems should more comprehensively monitor the prevalence, severity, treatment access, and outcomes for mental illness. Surveillance programs are discussed elsewhere in this issue of Preventing Chronic Disease (31).

- Research priorities should include models that elucidate causal pathways for mental illness in vulnerable populations.

- Research should evaluate the effect of race, culture, language, mental illness, and chronic disease on

illness and death and use the information to develop community engagement models.

- Programs and policies on mental health and illness should be integrated into the public health system.

- Federal agencies should collaborate to provide mental health care to incarcerated

and recently released populations.

- Professional employee training, recruitment, and retention activities should lead to effective mechanisms for a multicultural

mental health workforce.

A public health approach that promotes mental health among racial/ethnic minority populations and eliminates treatment disparities requires public policies that track and reduce disparities and seek solutions for these diverse communities. These goals will not be fulfilled quickly. They start with improving service programs, overcoming barriers to care, and building public health capacity.

Back to top

Author Information

Corresponding Author: Annelle B. Primm, MD, MPH, Minority and National

Affairs, American Psychiatric Association, 1000 Wilson Blvd, Ste 1825,

Arlington, VA 21287-7180. Telephone: 703-907-8539. E-mail:

aprimm@psych.org.

Author Affiliations: Melba J. T. Vasquez, American Psychological Association, Washington, DC; Robert A. Mays, National Institute of Mental Health, Bethesda, Maryland; Doreleena Sammons-Posey, National Association of Chronic Disease Directors and Directors of Health Promotion and Education, Trenton, New Jersey; Lela R. McKnight-Eily, Letitia R. Presley-Cantrell, Lisa C. McGuire, Daniel P. Chapman, Geraldine S. Perry, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia.

Back to top

References

- 2008 Population projections. US

Census Bureau; 2008.

http://www.census.gov/population/www/projections/2008projections.html.

Accessed September 30, 2009.

- New Freedom Commission on Mental Health. Achieving the promise: transforming mental health care in America. Final report. US Department of Health and Human Services; 2003. http://www.mentalhealthcommission.gov/reports/FinalReport/toc.html. Accessed August 10, 2009.

- Mental health: culture, race, and ethnicity. US Department of Health and Human Services; 2001. http://mentalhealth.samhsa.gov/cre/default.asp. Accessed September 14, 2009.

- US Public Law 106-525. Minority Health and Health Disparities Research and

Education Act of 2000.

- Mental health: a report of the Surgeon General. US Department of Health and Human Services; 1999. http://www.surgeongeneral.gov/library/mentalhealth/home.html. Accessed September 15, 2009.

- Manderscheid R. Evolving definitions of mental illness and wellness. Prev Chronic Dis 2010;7(1).

http://www.cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2010/jan/09_0124.htm.

- Beals J, Novins DK, Whitesell NR, Spicer P, Mitchell CM, Manson SM.

Prevalence of mental disorders and utilization of mental health services in two American Indian reservation populations: mental health disparities in a national context. Am J Psychiatry 2005;162(9):1723-32.

- Alegria M, Woo M, Takeuchi D, Jackson J. Ethnic group differences in mental health and service use: findings from the Collaborative Psychiatric Epidemiology Surveys. In: Ruiz P, Primm A, editors. Disparities in psychiatric care: clinical and cross-cultural perspectives. Bethesda (MD): Wolters Kluwer Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2009.

- Kessler RC, Demler O, Frank RG, Olfson M, Pincus HA, Walters EE, et al.

Prevalence and treatment of mental disorders, 1990 to 2003. N Engl J Med 2005;352(24):2515-23.

- Breslau J, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Kendler KS, Su M, Williams D, Kessler RC.

Specifying race-ethnic differences in risk for psychiatric disorder in a USA national sample. Psychol Med 2006;36(1):57-68.

- Strakowski SM, Keck PE Jr, Arnold LM, Collins J, Wilson RM, Fleck DE, et al.

Ethnicity and diagnosis in patients with affective disorders. J Clin Psychiatry 2003;64(7):747-54.

- West JC, Herbeck DM, Bell CC, Colquitt WL, Duffy FF, Fitek DJ, et al. Race/ethnicity among psychiatric patients: variations in diagnostic and clinical characteristics reported by practicing clinicians. Focus 2006;4(1):48-56.

- Wang PS, Berglund P, Kessler RC.

Recent care of common mental disorders in the United States: prevalence and conformance with evidence-based recommendations. J Gen Intern Med 2000;15(5):284-92.

- Daumit GL, Crum RM, Guallar E, Powe NR, Primm AB, Steinwachs DM, et al.

Outpatient prescriptions for atypical antipsychotics for African Americans, Hispanics, and whites in the United States. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2003;60(2):121-8.

- Hauenstein EJ, Petterson S, Rovnyak V, Merwin E, Heise B, Wagner D.

Rurality and mental health treatment. Adm Policy Ment Health 2007;34(3):255-67.

- Sentell T, Shumway M, Snowden L.

Access to mental health treatment by English language proficiency and

race/ethnicity. J Gen Intern Med 2007;22(Suppl 2):289-93.

- Singh GK, Hiatt RA.

Trends and disparities in socioeconomic and behavioural characteristics, life expectancy, and cause-specific mortality of native-born and foreign-born populations in the United States, 1979-2003. Int J Epidemiol 2006;35(4):903-19.

- Zhang AY, Snowden LR, Sue S. Differences

between

Asian

and

white

Americans’

help

seeking and

utilization patterns in the

Los

Angeles area. J Community Psychol 1998;26:317-26.

- Williams DR, Jackson PB.

Social sources of racial disparities in health. Health Aff (Millwood) 2005;24(2):325-34.

- Morland K, Wing S, Diez RA.

The contextual effect of the local food environment on residents’ diets: the

Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study. Am J Public Health 2002;92(11):1761-7.

- Gomez MB, Muntaner C. Urban redevelopment and neighborhood health in East Baltimore, Maryland: the role of communitarian and institutional social capital. Critical Public Health 2005;15(2):83-102.

- Iguchi MY, Bell J, Ramchand RN, Fain T.

How criminal system racial disparities may translate into health disparities. J Health Care Poor Underserved 2005;16(4 Suppl B):48-56.

- James DJ, Glaze LE. Mental health problems of prison and jail inmates. US Bureau of Justice Statistics; 2006. http://www.ojp.usdoj.gov/bjs/pub/pdf/mhppji.pdf. Accessed September 15, 2009.

- Jones CP, Truman BI, Elam-Evans LD, Jones CA, Jones CY, Jiles R, et al.

Using “socially assigned race” to probe white advantages in health status. Ethn Dis 2008;18(4):496-504.

- Miranda J, Bernal G, Lau A, Kohn L, Hwang W-C, LaFromboise T. State of the science on psychosocial intervention for ethnic minorities. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 2005;1:113-42.

- Snowden LR, Yamada A-M.

Cultural differences in access to care. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 2005;1:143-66.

- Harter M, Baumeister H, Reuter K, Jacobi F, Hofler M, Bengel J, et al.

Increased 12-month prevalence rates of mental disorders in patients with chronic somatic diseases. Psychother Psychosom 2007;76(6):354-60.

- Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR, editors. Unequal treatment: confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care.

Washington (DC): National Academies Press; 2003. http://www.nap.edu/catalog.php?record_id=10260. Accessed September 15, 2009.

- Sahota PK, Knowler WC, Looker HC.

Depression, diabetes, and glycemic control in an American Indian community. J Clin Psychiatry 2008;69(5):800-9.

- Feder A, Alonso A, Tang M, Liriano W, Warner V, Pilowsky D, et al.

Children of low-income depressed mothers: psychiatric disorders and social adjustment. Depress Anxiety 2009;26(6):513-20.

- Freeman EJ. Public health surveillance for mental health. Prev Chronic Dis 2010;(7):1.

http://www.cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2010/jan/09_0126.htm.

Back to top

|

|