Volunteer Fire Fighter Drowns After Being Thrown From His Swiftwater Rescue Boat - West Virginia

Death in the Line of Duty…A summary of a NIOSH fire fighter fatality investigation

Death in the Line of Duty…A summary of a NIOSH fire fighter fatality investigation

F2010-09 Date Released: January 25, 2011

Executive Summary

On March 13, 2010, at approximately 0615 hours, a 32-year-old volunteer fire fighter drowned after being thrown from a boat when it crashed into a bridge and capsized. The fire fighter was part of a swiftwater rescue team which included his captain and his chief. The chief was operating the boat as the crew attempted to make a fourth trip upstream to rescue civilians who were trapped by fast rising flood waters. The crew was navigating up an eddy created from the water flooding a street when the motor struck something under the water and diverted them out into the main current. The chief could not steer the motor, nor did it react when he put it into reverse. The boat slammed into a concrete bridge. The back of the boat was immediately pushed down into the water and the bow of the boat flipped up and over the stern throwing all three fire fighters into the frigid water. Two of the fire fighters were able to escape the hydraulics created from the flood water rushing against the arched concrete stanchion on the side of the bridge. The victim was recovered six days later approximately 4 miles from where the boat had capsized.

|

|

Rescue boat involved in incident. |

Contributing Factors

- Insufficient risk assessment analysis

- Personal protective ensemble not appropriate for cold water or flood conditions.

Key Recommendations

- Ensure that fire fighters wear the appropriate PPE for the environment encountered

Additionally, authorities having jurisdiction should

- Conduct a hazard and risk assessment analysis of their response areas to determine what resources are needed to conduct technical search and rescue at swiftwater incidents.

|

|

Position of rescue boat when initially pulled from river. |

Introduction

On March 13, 2010, at approximately 0615 hours, a 32-year-old volunteer fire fighter drowned after being thrown from a boat when it crashed into a bridge and capsized. On March 19, 2010, the U.S. Fire Administration notified the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health of this incident. On March 25-26, 2010, a Safety and Occupational Health Specialist from the NIOSH Fire Fighter Fatality Investigation and Prevention Program investigated this incident. Meetings were conducted with the state fire marshal’s office, fire department, county sheriff’s department, state police, and the state division of forestry. Interviews were conducted with fire fighters and officers and law enforcement officers who were involved with this incident, and the dispatch center. The investigator reviewed witness statements, dispatch logs, and the death certificate. The incident site was visited and photographed.

State Fire Marshal

During statewide emergencies, such as flooding, the state fire marshal’s office currently has the duties of calling volunteer and career departments throughout the state to determine what resources are available and who might be able to respond after an incident has occurred.

The state currently has regional response capabilities throughout six state regions. The teams’ response disciplines cover: Hazardous Materials/Weapons of Mass Destruction (WMD), Urban Search/Technical Rescue and Mass Casualty/Emergency Medical Service (EMS). The state currently does not have any regional response teams for its most frequent natural event, flooding, or require training for technical swift water teams to safely and effectively operate during these types of incidents.

Relevant NFPA Standards

National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) 1670, Standard on Operations and Training for Technical Search and Rescue Incidents,1 is an organizational training document which determines the organizational capability of a response organization. NFPA 1670 was developed to define levels of preparation and operational capability that should be achieved by any authority having jurisdiction (AHJ) who has the responsibility for conducting technical rescue operations. It does not apply to individuals.

NFPA 1006, Standard for Technical Rescuer Professional Qualifications was designed to establish the minimum job performance requirements necessary for fire service and other emergency response personnel who perform technical rescue operations. 2

State Training for Technical Search and Rescue

The state where this incident occurred does not have any formal requirements for fire fighters who respond to technical search and rescue incidents. They have approved training classes with various providers in the state that are compliant with the requirements set forth in NFPA 1670, but these training courses are not mandatory.3

The state defines the following operational levels for technical search and rescue:

Awareness Level: This level represents the minimum capability of a responder who, in the course of his or her regular duties, may respond to or be the first person on the scene of, a rescue incident. This level can involve limited search, rescue, and recovery operations. Members of a team at this level are generally, but not always, considered rescuers unless supervised by operations level or technician level personnel; or

Operations Level: This level represents the capability of hazard recognition, equipment use, and techniques necessary to safely and effectively support and participate in a technical rescue incident. This level can involve search, rescue, and recovery operations. Generally, but not always, operations level personnel are under the supervision of technician level personnel; or

Technician Level: This level represents the capability of hazard recognition, equipment use, and techniques necessary to safely and effectively coordinate, perform, and supervise a technical rescue incident. This level can involve search, rescue, and recovery operations. 4

Fire Department

This volunteer department consisted of 28 members in one station that serves a population of more than 3,000 people in a geographic area of approximately 14 square miles.

The victim and his department operated as mutual aid dispatched by the state fire marshal and worked under the Incident Command System established by the local fire department. The mutual aid crew functioned as a swiftwater rescue sector under the direction of the incident commander.

Training and Experience

The department involved in this incident receives their swiftwater certifications through a state regional education site. The courses taught at this location do not expire or require recertification. The department conducts numerous training courses with area swiftwater teams throughout the year. This training includes class room time and hands-on training in the local rivers with the department’s boat. These classes are conducted by certified swiftwater instructors. Members involved in this incident had both hands-on training and experience.

Incident Commander

The Incident Commander had more than 16 years of fire fighting experience and had completed training in topics such as:

Fire Fighter I and II

Fire Officer I

Swiftwater Awareness

Victim

The victim had more than 10 years of fire fighting experience and had completed training that qualified him to the State Awareness Level with regards to swiftwater incidents with these courses:

Swiftwater Boat Operations

Swiftwater Awareness

Boat Operator/Chief

The chief had more than 26 years of fire fighting experience and had completed training that qualified him to the State Technician Level with these courses:

Swiftwater Boat Operations

Swiftwater Awareness

Swiftwater Technician

Captain

The captain had more than 20 years of fire fighting experience and had completed training that qualified him to the State Technician Level with these courses:

Swiftwater Awareness

Swiftwater Boat Operations

Swiftwater Technician

Personal Protective Equipment

The victim was wearing a 3-mm neoprene wetsuit which was a sleeveless jumpsuit with a 2-mm neoprene full front zippered wetsuit jacket. He was wearing a sleeveless cotton shirt underneath the jacket and a Type-V rescue personal flotation device and a red protective helmet. His boots were a wetshoe workboot constructed of 5-mm neoprene upper with a 7-mm neoprene insole. The gloves he was wearing were made of 2-mm neoprene.

The personal protective gear ensemble of the other rescuers was identical except they were each wearing a dry suit. All ensembles, including the victim, met the criteria of NFPA 1670.

Weather

At the time of the incident, the temperature was approximately 50-degrees F° with light rain. The relative humidity was around 60 %. The winds were out of the east at roughly 3.5 mph.

Water Conditions

The area where the incident occurred had just suffered a severe storm that produced several inches of rain. The heavy rains, along with a substantial snow melt and run off from a local ski resort, resulted in flash flood conditions and extremely cold water. The water’s temperature was measured by the chief/boat operator the day that the incident occurred at 34-degrees F°.

Boat

The boat was a soft hull, hard deck, self bailing pontoon boat. It was approximately 14-feet long by 7-feet wide. The aluminum deck was approximately 10-feet long by 6-feet wide. The boat was powered by a 60-hp outboard motor. It was designed for use as a rescue boat for rough water conditions.

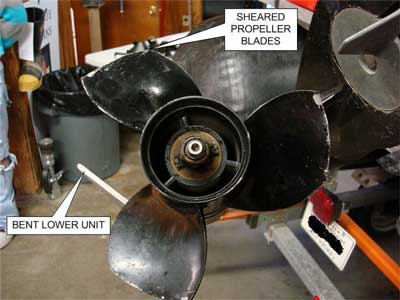

During this incident the engine suffered major damage. The boat was transported to the manufacturer for repair. The manufacturer reported that the driveshaft was bent and the lower unit and propeller were damaged (see Photo 1).

Investigation

On March 12, 2010, at approximately 2300 hours the chief of the department was contacted by his local dispatch and told to contact the state fire marshal regarding swift water operations. The state fire marshal directed the chief to contact the state office of emergency services who directed the chief that he was on standby to send a boat crew to assist a volunteer fire department over 1 ½-hours away from the chief’s department’s location. At approximately 0145 hours the department was contacted by dispatch for swiftwater operations and a five man crew was enroute by 0200 hours.

|

|

Photo 1. Picture of damaged lower unit and propeller. (NIOSH photo.) |

The chief and his crew returned to the staging area and received notice of other civilians stranded at a nearby location. The IC led the swiftwater crew to the location. The chief conducted a size-up of the situation prior to launching the rescue boat. The roadway was under water and there were four civilians standing on the roof of their car in waist deep water holding onto tree limbs. The chief deployed a three man crew which consisted of his captain, a fire fighter, and himself operating the rescue boat. The crew rescued the stranded civilians and turned them over to an ambulance crew for treatment. The swiftwater crew then proceeded to return to the staging area.

|

|

|

Photo 2 & Photo 3. The fire department had designated river-right and river-left from the downstream perspective. Both photos show view looking upstream at insertion point for rescue crews. Photo 3 was taken two weeks after incident. Houses in the background are where the residents were trapped. |

While enroute to the staging area the chief was notified that the power had been shut off and to respond to their previous location. Upon arrival, the crew had to wait until all of the power was shut off. The chief conducted a size-up of the area and noted that the original streambed, designated river-right, had the most current. An eddy, created by the water rising above the stream’s bank and designated as river-left, flooded the dead-end roadway where civilians were trapped (see Photo 2 and Photo 3). The chief conducted a brief safety meeting discussing the strategy for their rescue attempts and double checking everyone’s safety gear. The strategy consisted of two fire fighters, including the victim, wading in the water to turn the rescue boat around and assist with launching it up river, then retrieving it when it returned with the rescued civilians while the chief operated the rescue boat with the same captain and fire fighter that made the previous rescue.

The chief with the boat crew proceeded as planned up river-left in the eddy and noticed that all of the homes on the flooded roadway appeared to have water in them. They noticed a flashing light in one of the first homes and proceeded to that residence. The chief maintained control of the boat while the captain and the fire fighter assisted the civilians into the rescue boat. There were nine civilians in this residence including two infants and one adult confined to a wheelchair. The crew made three separate trips to rescue all of the civilians and transport them back to receive medical evaluation and treatment.

The chief was then advised that there were two elderly women in the first house on river-left and because of the water level, the chief was able to drive the rescue boat onto the front porch of the residence and rescue the two elderly women. The front porch of this residence is over eight feet off of the ground. The chief had the crew take a 15 minute break to warm up.

The chief was advised that there were two civilians trapped in the attic of one of the residences. The victim asked to go on the rescue boat and took the place of the other fire fighter. The chief, captain and the victim proceeded up river-left as they had in the other three rescues when the rescue boat and motor struck something under the water. The rescue boat made an immediate 90-degree turn to the left. The chief attempted to turn the boat but it did not respond. He then shifted the motor to reverse, but he was still unable to control the boat. The current caught the rescue boat and turned it another 90-degrees and it was headed directly towards the bridge. The chief yelled a warning to his crew as the bow of the rescue boat slammed into the bridge. The bow raised up from the force and the raging current forced the stern under the water. The boat immediately flipped bow to stern and threw the crew into the frigid water.

The crew was pulled under the water by the hydraulics created by the water rushing against the solid concrete bridge stanchion on the left hand side. The chief fought through the debris and the current caused by the hydraulics. The captain was doing the same thing. They both surfaced and then were pulled down under the water again. When the chief surfaced a second time, he heard his captain yell and he was able to grab a hold of him and provide assistance. The chief and his captain were stuck under the capsized rescue boat and were being pummeled by debris and the boat from the force of the flood water. The chief was able to make it to the bow of the boat while assisting his captain. A fire fighter on the bank from another department was able to pull the chief and the captain, who was now unconscious, from the water. As he was doing this, the victim popped up under the boat and attempted to reach out for assistance. The fire fighter immediately reached out for the victim as he cradled the chief and captain with one arm and his legs. Just as quickly as the victim surfaced, he was sucked under again for the final time. Everyone on-the-scene immediately spread out and searched downstream and other possible locations. Search efforts for the victim continued until he was located six days later approximately four miles downstream from the location of the incident.

Both seats in the vehicle were equipped with lap-style seat belts. Photos taken by the sheriff’s office investigators showed that the victim was not wearing his seat belt at the time of the incident. The injured fire fighter advised the NIOSH investigators that he was not wearing his seat belt during the incident.

Contributing Factors

Occupational injuries and fatalities are often the result of one or more contributing factors or key events in a larger sequence of events that ultimately result in the injury or fatality. NIOSH investigators identified the following items as key contributing factors in this incident that ultimately led to the fatality:

- Insufficient risk assessment analysis

- Personal protective ensemble not identified for cold water or flood conditions.

Cause of Death

The death certificate listed the cause of death as drowning and multiple force trauma.

Recommendations

Recommendation #1: The authority having jurisdiction should ensure that fire fighters wear the appropriate PPE for the environment encountered.

Discussion: In water rescue situations there are two different types of protective suits that are worn during operations. A wet suit allows water to seep through the material but does not circulate due to the snug fit of the garment. The wearer’s body temperature warms this layer of water creating a small insulating barrier against the cold. Wet suits are more comfortable to wear than dry suits and provide for easier body heat regulation during warmer months.

A dry suit, as its name implies, keeps the wearer dry and also provides isolation from body fluids and water contaminants commonly encountered in flood water rescue operations. Dry suits keep the wearer warm by adding an insulating barrier underneath and by protecting the wearer from the wind and cold water.

In both ensembles, cotton clothing should not be worn underneath. Cotton holds moisture and does not provide any insulation when wet, unlike wool and some synthetic materials.

Cold weather exposure results in the greatest number of drownings.5 The U.S. Coast Guard requires its members who are exposed to the possibility of water submersion to wear a dry suit when water conditions are 55-degrees and below.6 Water depletes heat from the body 25 times faster than air. When someone enters water that is 35-degrees F° or less the cold water may cause them to gasp and possibly aspirate water. They will lose or experience a decrease of muscle function that may render them unable to help themselves. 5 Thus at colder temperatures, a dry suit with underlying insulating garments provide greater thermal protection than a wet suit.

Wet suits do not provide protection for many contaminants found in flood water. Depending on the area of rescue, these contaminants may include pesticides, fertilizer, animal/human waste, industrial/commercial chemicals, and fuel oils. There has been at least one case of a fire fighter/ rescuer who became infected, and died, as a result of wearing a permeable protective ensemble rather than a body encapsulating drysuit. 7

The state follows NFPA 1670, Standard on Operations and Training for Technical Search and Rescue Incidents,1 which lists thermal protection but does not specify a temperature range. It is up to the AHJ to determine the appropriate level of thermal protection and protection from hazardous material contamination.

Recommendation #2: Authorities having jurisdiction should conduct a hazard and risk assessment analysis of their response areas and incident scene to determine what resources are needed to conduct technical search and rescue at swift water incidents.

Discussion: Technical rescue incidents are “low frequency/high risk” events. The primary purpose of risk assessment is to focus on incidents that might not occur very often (low frequency) but that could have severe consequences associated with them (high risk). The reason for the focus on low frequency/high risk incidents is that since they do not occur on a frequent basis, responders might not be as prepared to deal with them, and the outcomes can be harmful or detrimental to fire fighters.

According to NFPA 1670, Standard on Operations and Training for Technical Search and Rescue Incidents, a risk assessment should be conducted to analyze the factors that affect the frequency, scope, and magnitude of technical rescue incidents so that rescuers can safely respond to and work at these incidents.1

The state where this incident took place has several areas that are prone to flooding and require multiple technical swiftwater operations every year. The majority of the state encompasses rural communities, and the state fire marshal’s office currently has the duties of calling volunteer and career departments throughout the state to determine what resources are available and who might be able to respond after a swift water incident has occurred.

A hazard identification and risk assessment is an evaluation and analysis of the environment and physical factors influencing the scope, frequency, and magnitude of the technical rescue incidents and the impact and influence they can have on the ability of the authority having jurisdiction to respond to and safely operate at these incidents. The hazard identification and risk assessment determines “what” can occur, “when” (how often) it is likely to occur, and “how bad” the effects could be.

The state currently has regional response capabilities throughout six state regions. The teams’ response disciplines cover: Hazardous Materials/WMD, Urban Search/Technical Rescue and Mass Casualty/EMS. The state currently does not have any regional response teams for its most frequent threat to the health and safety of it citizens which is flooding. The state does not require training for technical swift water teams to safely and effectively operate during these types of incidents.

In this incident, the victim and his department operated as mutual aid dispatched by the state fire marshal and worked under the Incident Command System established by the local fire department. The mutual aid crew functioned as a swiftwater rescue sector under the direction of the Incident Commander. The authority having jurisdiction should establish the minimum qualification requirements for the responding personnel who perform technical rescue operations according to NFPA 1006.2

A state-based response unit could have provided the necessary, trained, qualified and properly outfitted personnel to assess, manage, and safely operate at a technical swiftwater incident. The authority having jurisdiction should determine and mandate from their risk assessment what is required from their response teams whether it is a state local or regional team(s) such as:

- Training requirements

- PPE requirements

- Staffing requirements for technical rescues

- Equipment requirements (secondary means of propulsion i.e. paddle or motor)

- Contingency plans for high hazard areas (operating above a bridge)

- Continuous risk assessment

- Low frequency/high risk incidents

- Scene size-up

- Risk management

- Incident Command System with swiftwater qualifications

References

- NFPA [2009]. NFPA 1670, standard on operations and training for technical search and rescue incidents. Quincy, MA: National Fire Protection Association.

- NFPA [2008]. NFPA 1006, standard for technical rescuer professional qualifications. Quincy, MA: National Fire Protection Association.

- State Fire Commission. [2007]. Requirements for Local Fire Departments.pdf iconexternal icon http://www.firemarshal.wv.gov/FireDepartmentServices/Documents/State%20Fire%20Commission%20-%20%20Requirements%20for%20WV%20Fire%20Departments%20102214.pdf. Date accessed: January 2011. (Link Updated 5/13/2015)

- State Fire Commission. [2005]. Requirements for Fire Department Rescue Services.external icon http://fireservice.ext.wvu.edu/r/download/31492 Date accessed: January 2011. (Link Updated 1/16/2013)

- WVU Fire Service Extension [2004]. Water Search and Rescue Awareness level Student Manual. Morgantown. WV: West Virginia University.

- US Coast Guard [2000]. Coast Guard Rescue Swimmer Manual, Section B.1. http://www.uscg.mil/directives/cim/3000-3999/CIM_3710_4B.pdf. Date accessed January 2011. (Link no longer available 12/6/2012)

- Firehouse.com [2004]. Pennsylvania Firefighter Dies After Working In Flood Cleanup; USFA Announces On Duty Death Almost Three Months Later.external icon http://www.firehouse.com/news/10514543/pennsylvania-firefighter-dies-after-working-in-flood-cleanup-usfa-announces-on-duty-death-almost-three-months-later. Date accessed: January 2011. (Link Updated 1/16/2013)

Investigator Information

This incident was investigated by Jay Tarley, Safety and Occupational Health Specialist, with the Fire Fighter Fatality Investigation and Prevention Program, Fatality Investigations Team, Surveillance and Field Investigations Branch, Division of Safety Research, NIOSH. Murrey Loflin, Associate Service Fellow, NIOSH, Division of Safety Research, provided technical support.

An expert technical review was provided by Slim Ray who is an internationally-recognized authority on flood, swiftwater and whitewater safety and rescue with twenty years of experience in swiftwater rescue. A technical review was also provided by the National Fire Protection Association, Public Fire Protection Division.

Disclaimer

Mention of any company or product does not constitute endorsement by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH). In addition, citations to Web sites external to NIOSH do not constitute NIOSH endorsement of the sponsoring organizations or their programs or products. Furthermore, NIOSH is not responsible for the content of these Web sites.

|

The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH), an institute within the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), is the federal agency responsible for conducting research and making recommendations for the prevention of work-related injury and illness. In 1998, Congress appropriated funds to NIOSH to conduct a fire fighter initiative that resulted in the NIOSH “Fire Fighter Fatality Investigation and Prevention Program” which examines line-of-duty-deaths or on duty deaths of fire fighters to assist fire departments, fire fighters, the fire service and others to prevent similar fire fighter deaths in the future. The agency does not enforce compliance with State or Federal occupational safety and health standards and does not determine fault or assign blame. Participation of fire departments and individuals in NIOSH investigations is voluntary. Under its program, NIOSH investigators interview persons with knowledge of the incident who agree to be interviewed and review available records to develop a description of the conditions and circumstances leading to the death(s). Interviewees are not asked to sign sworn statements and interviews are not recorded. The agency’s reports do not name the victim, the fire department or those interviewed. The NIOSH report’s summary of the conditions and circumstances surrounding the fatality is intended to provide context to the agency’s recommendations and is not intended to be definitive for purposes of determining any claim or benefit.

|

For further information, visit the program Web site at www.cdc.gov/niosh/fire or call toll free 1-800-CDC-INFO (1-800-232-4636).

This page was last updated on 02/18/2011.