Volunteer Lieutenant and a Fire Fighter Die While Combating a Mobile Home Fire - West Virginia

Death in the Line of Duty…A summary of a NIOSH fire fighter fatality investigation

Death in the Line of Duty…A summary of a NIOSH fire fighter fatality investigation

F2009-07 Date Released: October 1, 2009

SUMMARY

On February 19, 2009, a 49-year-old male volunteer lieutenant (Victim #1) and a 26-year-old male fire fighter (Victim #2) were fatally injured while combating a mobile home fire. They arrived on scene to find a camper fully involved with fire and flames impinging on an adjacent mobile home. The occupants of the camper and mobile home escaped without injury, prior to the fire department’s arrival. The victims entered the mobile home through the front door with a charged 1½-in hoseline. Within 5 to 10 minutes of them entering, the pump operator sounded the evacuation alarm when he noticed his tank water was low. The victims did not evacuate from the structure. Fire fighters on scene attempted to contact the victims via radio and by yelling into the mobile home. The fire chief and a fire fighter tugged on the 1½-in hoseline several times with no response. They then pulled on the hoseline and it came freely from the mobile home. Fire conditions were primarily contained to the one side of the structure while several attempts were made to locate the victims by fire fighters entering through the front door and noninvolved side of the mobile home. The victims were eventually discovered in the front room of the mobile home—several feet from the front door they had entered through. Their facepieces were not on when they were found. The victims were pronounced dead on scene. Key contributing factors identified in this investigation include lack of department administrative controls in regards to donning respiratory protection and SCBA maintenance, SCBAs were not equipped with an integrated or stand-alone PASS device, incident commander (IC) involvement in fireground activities, and wind conditions pushing smoke through the mobile home.

Incident Scene

(Photo courtesy of fire marshal)

NIOSH has concluded that, to minimize the risk of similar occurrences, fire departments should:

- ensure that fire fighters use their self-contained breathing apparatus (SCBA) during all stages of a fire due to the potential exposure and health affects of fire-produced toxins

- ensure that all SCBAs are equipped with an integrated personal alert safety system (PASS) device

- ensure that all fire fighters are equipped with a means to communicate with fireground personnel before entering a structure fire

- ensure that the incident commander (IC) does not become involved with fire fighting activities

- ensure that the incident commander (IC) maintains close accountability for all personnel operating on the fireground and that procedures and training for the use of a personnel accountability report (PAR) are in place

- ensure that a properly trained incident safety officer (ISO) is appointed at all structure fires

- ensure that a rapid intervention team (RIT) is established and available to immediately respond to emergency rescue incidents

- ensure that hoseline operations are properly coordinated so as not to impede search-and-rescue operations

- develop, implement, and enforce written standard operating procedures (SOPs) for fireground operations

- ensure that all fire fighters properly wear their department-issued turnout gear and personal protective equipment (PPE) during fire suppression activities

- develop and maintain a comprehensive respiratory protection program

- ensure that fire fighters are aware of the dangers involved in fighting mobile home fires

- ensure that policies and procedures for proper inspection, use, and maintenance of self-contained breathing apparatus (SCBA) are implemented to ensure they function properly when needed

INTRODUCTION

On February 19, 2009, a 49-year-old male volunteer lieutenant (Victim #1) and a 26-year-old male fire fighter (Victim #2) were fatally injured while combating a mobile home fire. On February 21, 2009, the U.S. Fire Administration notified the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) of this incident. On February 25, 2009, a safety and occupational health specialist and a safety engineer from the NIOSH Fire Fighter Fatality Investigation and Prevention Program investigated this incident. The NIOSH investigators interviewed the fire chief from the victims’ department and the fire marshals investigating the incident and visited the incident site. The NIOSH investigators returned March 2-March 4, 2009 with a second safety and occupational health specialist and conducted interviews with fire fighters and officers from the victims’ department and the mutual aid department that provided support in this incident. The investigators met with the state fire marshal and the state’s investigative team, reviewed their investigative photographs, spoke with the medical examiner, and photographed the victims’ gear and SCBAs. The investigators also met with the local 911 dispatch center.

NIOSH investigators also reviewed photographs of the fireground and training records of the victims and incident commander and toured the fire station. Although the performances of the victims’ SCBAs were not considered a factor in this incident, these SCBAs were examined by NIOSH’s National Personal Protective Technology Laboratory to determine conformity to the NIOSH-approved configuration (see Appendix for a summary of this examination).

The investigators spoke with the West Virginia Fire Extension Service regarding volunteer fire fighter requirements. The West Virginia Fire Extension Service also provided facilities and resources for NIOSH investigators to test the function of the nozzle that was on the hoseline when pulled into the mobile home by the victims. It had been secured by the state fire marshals at the incident scene immediately after the fatalities occurred. NIOSH investigators took the nozzle to the state fire service extension training center on April 3, 2009. The nozzle was connected to three 50 ft sections of 1 ¾-in preconnected hoseline on a 2001 model pumper. A qualitative test was conducted by NIOSH investigators in which water was flowed through the nozzle at varying stream patterns using pump pressures ranging from 80 to 150 psi. The nozzle was rated by the manufacturer to 70 to 200 gallons per minute at 100 psi. The actual flow was not measured. The nozzle appeared to function properly. NIOSH investigators recommend that the nozzle also be evaluated by the manufacturer or a certified test facility before it is placed back into service.

FIRE DEPARTMENT

Station 3—Victims’ Department. The victims’ volunteer department is comprised of 30 fire fighters. The department has one station and serves a rural population in a geographical area of 75 square miles. The fire department had established standard operating guidelines (SOGs) several years ago, but they were mostly administrative in nature and out-dated. The department is currently revising them.

Station 2—Mutual Aid Department. The mutual aid volunteer department is comprised of 34 fire fighters. The department has one station and serves a rural population in a geographical area of 170 square miles.

TRAINING AND EXPERIENCE

Victim #1 had been with this department for more than 11 years. He had completed certification courses in Fire Fighter I, Fire Officer I, Hazardous Materials Operations, Basic First Aid and Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation (CPR). The victim had also completed various online training courses on the incident command system (ICS).

Victim #2 had been with this department for more than seven months and was recently released from probationary status. Note: The fire department’s policy is to place all new members on probation until they complete the state requirements to be a volunteer fire fighter, which include Fire Fighter I, Hazardous Materials Awareness, Basic First Aid and CPR. Prior to joining this department he had been a volunteer fire fighter for approximately five years while stationed with the military in North Carolina and three years in another volunteer fire department in West Virginia. He had completed certification courses in Fire Fighter I, Hazardous Materials Operations, Basic First Aid, and CPR.

At the time of the incident, the IC served as the chief of the department. He had been a volunteer fire fighter with this department for more than 22 years and had been a command officer for approximately 15 years. He was certified to the levels of Fire Fighter II (NFPA 1001), Fire Instructor II, Hazardous Materials Technician, and Fire Officer II. He had also completed Leadership I – III, Incident Safety Officer, Managing Company Tactical Operations (Tactics, Decision Making, and Preparation), and several online and instructor-led courses in incident command systems.

This department periodically provided training to their members on topics such as use of personal protective equipment, SCBA, search and rescue, and water supply.

Equipment and personnel

- Station 3—Victims’ Department

Engine 30 (E30) with five fire fighters (Victim #1, Victim #2, an officer, FF1, pump operator)

Tanker 31 (T31) with three fire fighters

Engine 32 (E32) with five fire fighters

Special operations vehicle (SOV) with four fire fighters (FF2, FF3)

Privately owned vehicles (POVs) with fire chief (IC) and one fire fighter - Station 2—Mutual Aid Department

Utility 226 (U226) with three fire fighters (FF4)

Engine 224 (E224) with three fire fighters (FF5, FF6)

Privately owned vehicles (POVs) response by four fire fighters - Water Supply on Scene

E30 750 gallons

T31 1,500 gallons (not connected when evacuation alarm was sounded from E30)

E32 1,200 feet of 6-in supply hose laid from hydrant on main road to scene

Timeline

The timeline for this incident includes the initial call to the 911 dispatch center at 2156 hours. Only the units directly involved in the operations preceding the incident are discussed in this report. Once Station 3 arrived on scene all radio traffic went to their private repeater channel and was not heard or recorded by the county dispatch center. The response, listed in order of arrival and key events, includes:

- 2156 Hours

911 dispatch center receives a call from a civilian stating his “trailer” was on fire

Power company notified - 2157 Hours

Station 3 dispatched for mobile home fire - 2159 Hours

Fire chief en route

E30 en route

T31 en route - 2200 Hours

Fire chief on scene; requests law enforcement for traffic control

E30 on scene per fire chief - 2201 Hours

T31 on scene

E32 en route - 2203 Hours

E32 on scene; lays 6-in supply line to the scene - 2210 Hours

Law enforcement on scene; assists fire fighters in protecting the supply line on the main road - 2220 Hours

Station 2 dispatched to assist with manpower at mobile home fire - 2226 Hours

E224 en route

U226 en route - 2236 Hours

Fire chief requests manpower assistance because two of his men are missing

U226 on scene - 2239 Hours

E224 on scene

PERSONAL PROTECTIVE EQUIPMENT

It was reported to NIOSH investigators that Victim #1 and Victim #2 were seen wearing a full array of personal protective clothing and equipment, consisting of turnout gear (coat and pants), helmet, Nomex® hood, gloves, boots, and a self-contained breathing apparatus (SCBA). It could not be determined whether the victims were on air when they entered the mobile home. Victim #1’s Nomex® hood met the 1997 edition of NFPA 1971 and Victim #2’s Nomex® hood met the 1991 edition of NFPA 1971; the victims’ structural fire fighting rubber boots and turnout gear (manufactured in March of 2002) met the 2000 edition of NFPA 1971. The turnout gears’ heat-resistant outer shells, moisture barriers, and insulating thermal linings were all present during the incident and documented during the investigation.

The victims were found equipped with a flashlight and various fire fighter hand tools in their pockets. Victim #1 was found without his helmet on and Victim #2 still had his on. The victims were also found with their Nomex® hoods rolled down on their necks, without their facepieces on, and without a stand-alone or integrated PASS device.

The department used SCBAs from two different manufacturers.a Some SCBAs in the department used low pressure tanks and others used high pressure tanks, and many first-out and spare air bottles had not been hydrostatically tested. Note: A hydrostatic test is a testing method that uses water under pressure to check the integrity of pressure vessels. Air cylinders must be stamped or labeled with the manufactured date and the date of the last hydrostatic test. According to the U.S. Department of Transportation, steel and aluminum cylinders must be tested every five years; composite cylinders every three years.1 Some SCBAs had integrated PASS devices and some had only stand-alone PASS devices attached to the harness. The SCBAs that the victims used did not have an integrated PASS device and were recently placed on the fire apparatus for use without a stand-alone PASS placed on them. Stand-alone PASS devices were shared among department SCBAs that did not have an integrated PASS.

The victims’ face-mounted regulators were connected securely to the SCBAs’ assigned facepieces and were hanging at waist level. Soot was found on the outside and inside of both facepieces when photographed by the fire marshal. Victim #2’s facepiece was missing the lower left fastener that anchors the harness to the facepiece (see Photo 1). Both face-mounted regulators were last flow-tested in March of 2002. Note: The members were not issued their own facepieces, but rather shared a universal facepiece assigned to each SCBA. During the investigation, many members, including incident photos viewed of Victim #1, were observed with excessive facial hair or beards. Also, both remote pressure gauges were found to be in the “empty” position. Note: Records were not provided to NIOSH investigators to determine the initial air cylinder readings. The air cylinder gauges were damaged and unreadable.

a The SCBAs that were primarily used by this department were the subject of a recent NIOSH user noticepdf icon that can be found at https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/npptl/usernotices/pdfs/GSSPI1_11202008.pdf. However, this model of SCBA was not used by the victims on the night of the incident.

Photo 1. Facepiece missing a harness fastener.

(NIOSH photo)

STRUCTURE

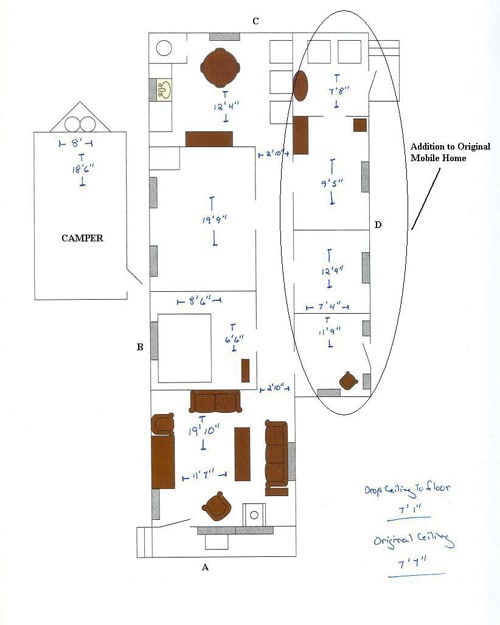

The incident structure was a single-story, single-wide mobile home built between 1970 and 1980. The mobile home had approximately 980 ft2 of furnished living space (65 x 12 ft mobile home and a 41 ft 6 in x 7 ft 4 in addition, D-side) (see Diagram #1). The mobile home was of wood-frame construction with aluminum siding, flat metal roof, and linoleum floors throughout the home. The walls were fiberglass-insulated under particle board and covered with sheets of finished wood paneling. The home had drop-ceiling panels rested in a suspended grid system that measured 7 ft 1 in to the floor. Fiberglass insulation was placed in the 6-in void space between the drop ceiling and original ceiling. The home had a wood-burning stove at the A-D corner.

The fire originated from an occupied camper that was parked near the B-side of the mobile home, approximately four feet away (see Photos 2 and 3). The camper measured 18 ft 6 in x 8 ft and was completely destroyed during the fire. It is believed the camper fire directly impinged on the B-side of the structure causing a window to fail, allowing the fire to ignite the B-side wall and bedroom materials inside the mobile home.

Diagram 1. Approximate dimensions of mobile home.

(Diagram courtesy of fire marshal; with added labels)

|

|

| Photos 2 and 3. Camper located on the B-side of the structure. Photos taken after snow had melted. (Photos courtesy of fire marshal) |

|

Weather

The weather at the time of the incident was cloudy with snow and a temperature of 21°F, a wind of 13 mph and gusts upwards of 24 mph blowing west-northwest.

INVESTIGATION

On February 19, 2009, at 2156 hours, the 911 dispatch center received a 911 call from a civilian stating his “trailer” was on fire. The initial dispatch included Station 3 at 2157 hours. The initial on-scene conditions were not reported by arriving personnel, but during interviews fire fighters stated the camper was fully involved with fire and flames impinging on the mobile home. The occupants of the camper and mobile home were able to evacuate without injury prior to the fire department’s arrival.

Activities of the Incident Commander

The fire chief arrived on scene at 2200 hours. The fire chief blocked traffic with his POV allowing E30 and T31 to position into the incident scene. Because he was the highest ranking officer on scene, the fire chief assumed the role of IC, following the department’s SOPs. The IC did not provide to dispatch an incident size-up nor did he state that he was in command upon his arrival. Note: The fire chief and initial apparatus responded together from the fire station. Fire fighters interviewed stated they were aware that the fire chief was the IC because he was the highest ranking officer on scene. After T31 passed his position, the IC followed T31 into the scene and saw a hoseline stretched in the mobile home through the A-side door. The IC never saw Victim #1 or Victim #2 enter the mobile home. He also saw two fire fighters spraying water on a fully involved camper that was sitting next to the mobile home. He stated that he did not see the mobile home on fire, but the fire from the camper was hitting the B-side of the mobile home.

The porch light was still on and the IC thought he could see the interior lights on as well. He immediately exited his vehicle and walked around the mobile home performing his size-up and trying to locate the electric meter. He noticed that the meter was positioned across the residential street from the mobile home. He asked a fire fighter, who responded in a POV, to stand on the A-side porch of the mobile home and let him know when the power went out. Note: This fire fighter stated that the smoke was heavy and gray, hanging in the mobile home, but he could see 10 ft inside the mobile home from the doorway. The IC pulled the electric meter and then heard the evacuation alarm sound from E30. Note: The IC could still see the incident scene from where the meter was pulled.

The IC walked over to E30 and asked the pump operator why the alarm was sounding. He then realized the initial attack crew had not come out. The IC and the fire fighter assigned to the front porch tugged several times on the 1½-in hoseline running through the A-side door and eventually pulled it out with no response from the victims. The IC stated it was a normal practice for him to pull on the hoseline to get his fire fighters to respond if they didn’t respond initially to the evacuation alarm. He asked the pump operator for a head count. The pump operator advised the IC his head count was five, but he did not know who went in from E30. The IC called a member back at the fire station to confirm who responded on E30. The IC then walked around the mobile home to see if Victim #1 and Victim #2 exited through a different door. He tried to contact the victims by radio while other fire fighters on scene yelled through the front and rear doors. Note: It was later determined that both victims had left their assigned radios at the station. He noticed two fire fighters were flowing water with a 2½-in hoseline at the C-D corner of the mobile home trying to extinguish the fire and locate the victims. The IC instructed two fire fighters, FF2 and FF3 (arrived by SOV) from Station 3, to “pack-up” and enter through the A-side door to search for the victims. He stated that heavy gray smoke was coming from this door, but no fire was present. He then assisted the pump operator of E32 in placing that apparatus into pump service so that they could supply E30. The IC then contacted the state fire marshal’s office to report the missing fire fighters and to request additional manpower assistance as well.

The IC was notified of failed attempts to locate the victims in the A-side front room. Note: FF2 and FF3 entered to find conditions to be very hot, with black smoke and fire rolling across the ceiling. They exited after running out of air, and then one fire fighter from Station 2 (FF4) and FF2 reentered to find the same conditions. The IC then noticed the officer of E30 coming around the A-D corner with the 2½-in hoseline that was being used at the C-D corner. The IC took the hoseline, set the nozzle to fog, and sprayed it through the A-side door which improved visibility.

Activities of E30

E30 arrived on scene at 2200 hours. The crew from E30 reported the camper, located on the B-side of the mobile home, being fully involved upon their arrival and flames impinging on the mobile home. Light gray smoke was also visible around the mobile home. E30 was positioned at the A-B corner with T31 pulling in behind E30. Victim #1 and Victim #2 pulled a 150-ft preconnected 1½-in hoseline off the officer side of the engine and positioned it at the front door (A-B corner) of the mobile home. The E30 officer and Fire Fighter #1 (FF1) pulled a second 150-ft preconnected 1½-in hoseline off the officer side of the engine and positioned it at the camper (B-side of mobile home). Victim #1 then walked over to the E30 officer and pointed at the mobile home, indicating he was going inside. That was the last time the E30 officer saw Victim #1. The E30 officer could not recall whether the victims were wearing their facepieces when they entered the mobile home.

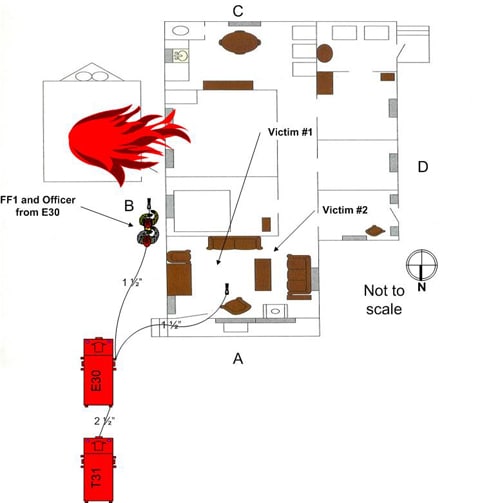

The E30 officer flowed water from the A-B corner of the mobile home diagonally across the camper trying to keep the fire off the mobile home. He then went to the opposite side of the camper and flowed water onto it. The camper walls were coming down and he believed that the hose stream may have pushed into the mobile home’s B-side. He then heard the evacuation alarm sound from E30 (see Diagram 2).

The pump operator sounded the evacuation alarm after he noticed that the panel light indicating a half-tank capacity was no longer illuminated. Note: Fire marshals estimated the evacuation alarm was sounded within 10-15 minutes of E30’s arrival. He stated that the panel light indicating a quarter-tank capacity was not working. He sounded the evacuation alarm at this time because he wanted to make sure that the fire fighters inside the mobile home had enough water to get out in case the fire was not extinguished. He sounded the alarm three times with no response from the interior crew.

The E30 officer left the hoseline with FF1 positioned at the camper and went back to E30 to see what was happening. He was told by the E30 operator that the victims had not exited the mobile home, so he took a 2½-in hoseline from E30 around to the D-side of the mobile home. With assistance from two Station 2 members (FF5 and FF6), the officer flowed water on the mobile home’s addition and through the rear door located at the C-D corner. FF5 and FF6 entered through the D-side door and fought fire until they ran out of air. The officer then went back to the A-side of the structure with the 2½-in hoseline; the IC took the 2½-in hoseline from the officer and sprayed a fog pattern through the front door. The fog pattern pushed the smoke back, allowing the officer and a Station 3 fire fighter (FF2) to enter the mobile home where they discovered Victim #1 on the floor approximately 10 feet from the front door and Victim #2 approximately sixteen feet from the door.

Activities of T31

T31 arrived on scene at 2201 hours and positioned behind E30. T31 connected a section of 2½-in supply line to E30 to provide them with their tank water. As T31 was connecting to E30 the evacuation alarm was sounded. The pump operator immediately looked at the mobile home and saw smoke around the front door, but no fire. He then quickly filled E30’s tank. The pump operator then assisted E32 in supplying E30. Note: T31 was initially used for its tank water and did not supply E30, after E32 laid a supply line into the scene. The pump operator remembers the IC, the fire chief, briefly assisting the crew of E32 when they could not get E32 to pump.

Activities of E32

E32 arrived on scene at 2203 hours and connected to the hydrant located on the main road. They laid 1,200 ft of 6-in supply line to the incident scene. They were short; therefore 100 ft of 2½-in supply line was laid from E32 to E30 to supply them with water. Initially, E32 would not pump due to being in the wrong gear. The IC was able to fix the problem and a viable water supply was established to E30.

Activities of Station 2

Station 2 was dispatched to assist with manpower with U226 arriving at 2236 hours and E224 arriving at 2239 hours. All apparatus from Station 2 were staged on the main road. The IC tasked two fire fighters in full turnout gear and SCBA (FF5 and FF6) to go to the C-D corner to assist E30’s officer, FF4 was tasked to the A-side to assist with search and rescue, and one fire fighter to assist with extinguishing the camper fire.

FF5 and FF6 took a 2½-in hoseline in through the D-side door; no smoke was coming out of this door. They entered into what was later determined to be the kitchen area. They went in standing up and were met with gray to black smoke. They turned left from the kitchen and noticed fire coming from a bedroom on the B-side. They started flowing water on the flames with a straight stream when, while advancing down the hall, FF5 fell through the floor. FF5 stated he held onto the nozzle while flowing water down the hallway. FF6 immediately assisted FF5 up, and they went to their knees to fight the fire. FF5 changed the straight stream pattern to a fog pattern and placed the nozzle through the bedroom wall that had been breached by fire. They sprayed water for 10-15 minutes before their low-air alarms sounded.

FF2 (from Station 3) and FF 4 entered through the A-side front door. FF4 recalls seeing no fire conditions in the front room and the gray/black smoke was being blown around them. He was able to walk around the front room and remembers walking on a lot of debris. The suspended ceiling had fallen allowing the fiberglass insulation to fall, covering the living room floor and the victims (see Photos 4 and 5).

|

|

|

Photos 4 and 5. Front room of mobile home before and after debris and victims were removed. |

|

Discovery of Victims

Victim #1 was found 9 ft 10 in and Victim #2 was found 15 ft 11 in from the A-side door they entered through. Note: These measurements were taken from the doorway to the victims’ closest extremities. Victim #1 was face down with his arms by his side and legs straight. His regulator was connected to his facepiece and was discovered under him at waist level. His body was positioned toward the C-side of the mobile home. His helmet was found sitting upright on a couch several feet away from him as if he had taken it off and laid it on the couch. Victim #2 was found 1 ft 10 in ahead of Victim #1, also face down. His left leg was bent under his right leg, right arm under his body, and left arm facing up. His regulator and facepiece were also connected and discovered under his body at waist level. His body was also pointing toward the C-side of the mobile home. Both victims had their Nomex® hoods rolled down on their necks. Also, both victims were found without an integrated or stand-alone PASS device.

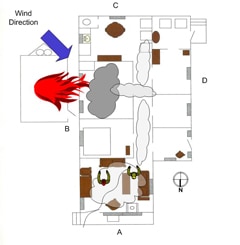

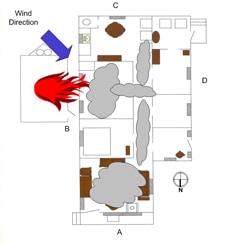

State fire marshal and NIOSH investigators have not been able to determine what happened in the mobile home causing the deaths of the two fire fighters. According to the medical examiner, both victims had lethal doses of carbon monoxide and cyanide in their systems, thermal burns to their tracheas, and soot in their lungs. NIOSH investigators believe that the victims may have entered the structure without being on air because there was no evidence of fire within the mobile home, only light smoke. Note: Fire fighters interviewed stated if no fire was present and smoke conditions were light, then the department fire fighters may not have initially been on air. It is believed that while advancing the hoseline into the front room, the camper fire continued to directly impinge on the mobile home, causing materials to heat up and off-gas until they reached their ignition temperature; fire from the camper also breached into the interior of the mobile home through a B-side window. The windy conditions and the mobile home acting as a horizontal chimney may have contributed to the movement of products of combustion, smoke toxins, and hot fire gases through the mobile home, which could have quickly overcome the victims (see Diagrams 3 and 4).

|

|

| Diagrams 3 and 4. Diagram on left depicts smoke and visibility conditions when fire fighters entered into the mobile home, with the gray cloud indicating heavy smoke and products of combustion and the transparent clouds indicating lighter smoke conditions and good visibility. NIOSH investigators believe that smoke and visibility conditions quickly changed engulfing the fire fighters in an oxygen-deficient atmosphere and exposing them to fire-produced toxins, with the gray clouds indicating increased smoke conditions and products of combustion (Diagram on right). | |

CONTRIBUTING FACTORS

Occupational injuries and fatalities are often the result of one or more contributing factors or key events in a larger sequence of events that ultimately result in the injury or fatality. NIOSH investigators identified the following items as key contributing factors in this incident that may have led to the fatalities:

- Lack of department administrative controls in regards to donning respiratory protection and SCBA maintenance.

- SCBAs were not equipped with an integrated or stand-alone PASS device.

- Incident commander involvement in fireground activities.

- Wind conditions pushing smoke through the mobile home.

CAUSE OF DEATH

According to the county medical examiner’s office, the victims died from smoke inhalation and thermal inhalation burns. The carboxyhemoglobin (COHb) levels were 63% for Victim #1 and 64% for Victim #2. The toxicology reports for both victims showed lethal doses of cyanide in their systems.

RECOMMENDATIONS/DISCUSSIONS

Recommendation #1: Fire departments should ensure that fire fighters use their self-contained breathing apparatus (SCBA) during all stages of a fire due to the potential exposure and health affects of fire-produced toxins.

Discussion: An SCBA is a device that allows fire fighters to operate safely within an environment with inhalation hazards such as toxic smoke and oxygen deficiency,2 defined by OSHA as immediately dangerous to life and health (IDLH). OSHA 29 CFR 1910.134 (g) (4) (iii) states, “all employees engaged in interior structural firefighting use SCBAs.”3 During this incident, it is believed that the victims entered the mobile home without being on air and were overcome by toxins in the smoke and hot fire gases. Fire fighters on scene reported light smoke conditions within the mobile home when the victims entered. The B-side of the mobile home received direct flame impingement from the camper fire, causing materials to off gas until they reached their ignition temperature. A sustained wind of 13 mph with gusts of 24 mph blowing toward the A-D corner of the mobile home may have contributed to conditions that overcame the victims.

The medical examiner stated both victims received thermal burns to their tracheas and soot was discovered in their lungs, which were indications that they had taken several breaths of superheated gases and smoke. They sustained very minor thermal burns to exposed skin areas. The medical examiner also indicated that the victims’ COHbs levels (a measure of carbon monoxide in the bloodstream) were over 60% and both contained lethal doses of cyanide. In the absence of carbon monoxide, the victims’ cyanide levels alone were enough to be fatal. Studies conducted in 19914 and 19885 showed that cyanide and carbon monoxide may potentiate the toxic effects of one another.6 The medical examiner advised NIOSH investigators that both victims’ skin color was cherry red which is an indication of exposure to carbon monoxide and cyanide.

It is important for fire fighters to understand that as temperatures increase in the initial stages of a fire, plastics begin to give off large quantities of various gases. This is called quantitative decomposition, and it happens long before materials reach their ignition temperatures.7 Hydrogen cyanide is a colorless, odorless gas that is released from plastics, natural and synthetic building components, and household items like carpet fibers and polyurethane foam cushions, all of which were present in the structure. Symptoms of exposure include confusion, involuntary muscle movement, vertigo, shortness of breath, or coma.6 Carbon monoxide is a by-product of incomplete combustion which can be present before fire fighters visualize fire, and its exposure will present in the same manner as hydrogen cyanide.

Even if nothing but carbon dioxide, water vapor, and nitrogen were present in the fire products, and these were to mix with the air being breathed by a fire fighter, then the oxygen percentage would be reduced below the normal 21%. At 15% oxygen, fire fighters can experience lethargy, poor coordination, and confused thinking. The two principal toxins in smoke—carbon monoxide and hydrogen cyanide—act to deprive the brain of oxygen, and their effects would be enhanced due to the lower levels of oxygen in the air.8 Exposures to these types of respiratory hazards can be reduced or eliminated by the mandatory use of SCBA during all fire suppression and overhaul operations.

Recommendation #2: Fire departments should ensure that all SCBAs are equipped with an integrated personal alert safety system (PASS) device.

Discussion: NFPA 1500 Standard on Fire Department Occupational Safety and Health Program states, “each member shall be provided with, use, and activate his or her PASS devices in all emergency situations that could jeopardize that person’s safety due to atmospheres that could be IDLH, in incidents that could result in entrapment, in structural collapse of any type, or as directed by the incident commander or incident safety officer.”9 The intent of the PASS device is to emit an audible warning signal that other fire fighters can hear in the event a fire fighter becomes incapacitated or requires help. The PASS device operates in either manual or automatic mode. Fire fighters can manually operate their device when they find themselves in trouble; the automatic mode will operate when the fire fighter is not moving for a period of time, approximately 30 seconds. During the fire marshal’s investigation it was discovered that the victims were using SCBAs that did not have an integrated or stand-alone PASS device.

Recommendation #3: Fire departments should ensure that all fire fighters are equipped with a means to communicate with fireground personnel before entering a structure fire.

Discussion: NFPA 1561 Standard on Emergency Services Incident Management System states, “to enable responders to be notified of an emergency condition or situation when they are assigned to an area designated as immediately dangerous to life or health (IDLH), at least one responder on each crew or company shall be equipped with a portable radio and each responder on the crew or company shall be equipped with either a portable radio or another means of electronic communication.”10 Radio communications on the fireground is imperative for the IC to command and control the incident and for fire fighters working within a structure fire. Fire fighters within a structure are unable to see all areas affected by fire and whether the structure is maintaining its stability. Having radio communications can enhance fire fighter safety and health by providing them a means to communicate with other crew members or with the IC when they find themselves in need of assistance.

This fire department recently issued portable radios to all active members. On the night of the incident, the victims were discovered within the mobile home without their department-issued radios. Their radios were later found at the fire station.

Recommendation #4: Fire departments should ensure that the incident commander (IC) does not become involved with fire fighting activities.

Discussion: NFPA 1561 Standard on Emergency Services Incident Management System states, “the Incident Commander shall be responsible for the overall coordination and direction of all activities at an incident.” In addition to conducting an initial size-up, the IC should maintain a command post outside the structure to assign companies and delegate functions and continually evaluate the risk versus gain of continued fire fighting efforts.9 According to the International Fire Service Training Association (IFSTA) publication, Fire Department Company Officer, there are three modes of operation for the first-arriving officer assuming IC: nothing showing, fast attack, and command.11

During this incident, the conditions at this incident suggested the need to implement the command mode of operation. The first arriving officer should assume command by naming the incident and designating the command post, giving an initial report on conditions, and requesting additional resources as needed. In this incident, the IC became involved with fireground activities including traffic control, pulling the electrical meter, and helping with pump operations. These tasks took the IC’s attention away from initial fire fighting activities of the victims and search and rescue activities of other fire fighters. Being able to command and control the incident scene requires the IC to be cognizant of all directed tasks and evolving conditions.

Recommendation #5: Fire departments should ensure that the incident commander (IC) maintains close accountability for all personnel operating on the fireground and that procedures and training for the use of a personnel accountability report (PAR) are in place.

Discussion: An important aspect of an accountability system is the personnel accountability report (PAR). A PAR is an organized on-scene roll call in which each supervisor reports the status of his crew when requested by the IC or emergency dispatcher.1 The use of an accountability system is recommended by NFPA 1500 Standard on Fire Department Occupational Safety and Health Program9 and NFPA 1561 Standard on Emergency Services Incident Management System.10 A functional personnel accountability system requires the following:

- development of a departmental SOP

- training all personnel

- strict enforcement during emergency incidents

In this department each apparatus operator was responsible for the names and head count of personnel riding on that apparatus. During this incident, the IC requested a head count when the operator of E30 sounded the evacuation alarm. Although the number of members who arrived on the engine was known, the identities of arriving members were not known and a call back to the station was needed. After determining who was missing, the IC then went looking for the victims on the fireground. A properly initiated and enforced accountability system that is consistently integrated into fireground command and control enhances fire fighter safety and survival by helping to ensure a more timely and successful identification and rescue of a disoriented or downed fire fighter.

Recommendation #6: Fire departments should ensure that a properly trained incident safety officer (ISO) is appointed at all structure fires.

Discussion: NFPA 1521 Standard for Fire Department Safety Officer defines the role of the ISO at an incident scene and identifies duties such as reporting pertinent fireground information to the IC; ensuring the department’s accountability system is in place and operational; monitoring radio transmissions and identifying barriers to effective communications; and ensuring that established safety zones, collapse zones and other designated hazard areas are communicated to all members on scene.12 The presence of a safety officer does not diminish levels of personal responsibility that each fire fighter and fire officer must assume for their own safety and the safety of others. Instead, the ISO adds a higher level of attention and expertise to help individuals on the fireground monitor their own safety and the IC to manage the scene. The ISO must have particular expertise in analyzing safety hazards and must know the particular uses and limitations of protective equipment.10 During this incident no incident safety officer was established to assist the IC in accountability, fire fighter safety, or ensuring the donning of personal protective equipment.

Recommendation #7: Fire departments should ensure that a rapid intervention team (RIT) is established and available to immediately respond to emergency rescue incidents.

Discussion: A RIT should be designated and available to respond before interior attack operations begin. The team should report to the IC and be available within the incident’s staging area. The RIT should have all tools necessary to complete the job, e.g., search and rescue ropes, Halligan bar and flat-head axe combo, first-aid kit, and resuscitation equipment.1 These teams can intervene quickly to rescue a fire fighter who is running out of breathing air, disoriented, lost in smoke-filled environments, trapped by fire, or involved in structural collapse.9

During this incident the department members who were properly trained as a RIT member were not present and a RIT team was not established. The IC chose who would perform search and rescue operations from the available personnel on scene due to their experience.

Recommendation #8: Fire departments should ensure that hoseline operations are properly coordinated so as not to impede search-and-rescue operations.

Discussion: When a hose nozzle is opened it forces a certain amount of air ahead of the pattern, and replacement air is drawn in behind the nozzle.13 Hydraulic ventilation is the use of a fog pattern through a window or door opening that draws large quantities of heat and smoke in the direction in which the stream is pointed.

During this incident, fire fighters entered the mobile home through the D-side door with a 2½-in hoseline. They began flowing water on a straight stream setting as they entered the kitchen area spraying hot spots as they progressed to the hallway. Once in the hallway, the nozzle was switched to a fog pattern and directed down the hallway toward the A-side for a period of time. Search and rescue crews were operating in the front room on the A-side and complained of heat and smoke whirling around. The narrowness of the hallway acted as a tunnel forcing heat and smoke toward the crews and hampering their efforts to find the victims quickly.

The hose crew backed out of the mobile home, after running out of air, taking the hoseline around to the A-side. The IC took the hoseline from the crew, set the nozzle to fog and sprayed it into the A-side door. Smoke and heat immediately dissipated in the front room allowing the search crews to immediately find the victims.

Recommendation #9: Fire departments should develop, implement, and enforce written standard operating procedures (SOPs) for fireground operations.

Discussion: Written SOPs enable individual fire department members an opportunity to read and maintain a level of assumed understanding of operational procedures. Conversely, fire departments can suffer when there is an absence of well developed SOPs. The NIOSH Alert, Preventing Injuries and Deaths of Fire Fighters identifies the need to establish and follow fire fighting policies and procedures.14 To be effective, guidelines and procedures should be developed, fully implemented, and enforced. The following NFPA standards also identify the need for written documentation to guide fire fighting operations:

NFPA 1500 Fire Department Occupational Safety and Health Program states that “fire departments shall prepare and maintain written policies and standard operating procedures that document the organizational structure, membership, roles and responsibilities, expected functions, and training requirements, including the following: The procedures that will be employed to initiate and manage operations at the scene of an emergency incident.”9

NFPA 1561 Standard on Emergency Services Incident Management System states that standard operating procedures (SOPs) shall include the requirements for implementation of the incident management system and shall describe the options that are available for application according to the needs of each particular situation.10

NFPA 1720 Standard for the Organization and Deployment of Fire Suppression Operations, Emergency Medical Operations, and Special Operations to the Public by Volunteer Fire Departments states that the authority having jurisdiction shall promulgate the fire department’s organizational, operational, and deployment procedures by issuing written administrative regulations, standard operating procedures, and departmental orders.15

NIOSH investigators received a copy of the fire department’s standard operating guidelines (SOGs). The fire chief explained that the SOGs were outdated and in the process of being revised. These SOGs contained mostly administrative guidelines and did not contain detailed fireground operation procedures that would enhance fire fighter safety and health and overall incident stabilization.

It is important to understand the difference between a policy and a procedure, also known as a guideline. A department policy is a guide to decision making that originates with or is approved by top management in a fire department. Policies define the boundaries within which the administration expects department personnel to act in specified situations. A procedure is a written communication closely related to a policy. A procedure describes in writing the steps to be followed in carrying out organizational policies. SOPs are standard methods or rules in which an organization or a fire department operates to carry out a routine function. Usually these procedures are written in a policies and procedures handbook and all fire fighters should be well versed as to their content.1 Operational procedures that are standardized, clearly written, and mandated to each department member establish accountability and increase command and control effectiveness.1 The benefits of having clear, concise, and practiced SOPs are numerous. For example, SOPs can become an outline for training curriculum and a tool to guide fire department members. Above all, successfully integrated SOPs improve departmental safety.16

Recommendation #10: Fire departments should ensure that all fire fighters properly wear their department-issued turnout gear and personal protective equipment (PPE) during fire suppression activities.

Discussion: NFPA 1500 Standard on Fire Department Occupational and Health Program states, “the fire department shall provide each member with protective clothing and protective equipment that is designed to provide protection from the hazards to which the member is likely to be exposed and is suitable for the tasks that the member is expected to perform…protective clothing and protective equipment shall be used whenever a member is exposed or potentially exposed to the hazards for which the protective clothing (and equipment) is provided.”9

Both victims were discovered with their Nomex® hoods rolled down on their necks. Victim #1’s helmet was found melted on a couch next to Victim #2 as if it had been taken off and laid there. Both victims’ facepieces were found hanging at waist level with their regulators attached, possibly indicating that they were stored in this manner. NFPA 1971 Standard on Protective Ensembles for Structural Fire Fighting and Proximity Fire Fighting has established minimum requirements for structural fire fighting protective ensembles and ensemble elements designed to provide fire fighting personnel limited protection from thermal, physical, environmental, and bloodborne pathogen hazards encountered during structural fire fighting operations.17 These requirements will assist in protecting firefighters, but only if they wear the PPE as recommended by the manufacturer.

Recommendation #11: Fire departments should develop and maintain a comprehensive respiratory protection program.

Discussion: Fire fighting is a physically and psychologically demanding occupation that requires strength, physical agility, and endurance as well as the ability to operate effectively with the limitations created by a SCBA and other personal protective equipment. A fire fighter may have the physical ability to perform functions, such as hose advancement or rescuing victims, but should be trained in performing those functions while vision is obscured and movement is restricted (e.g., while using required personal protective equipment such as SCBA). Fire departments should recognize and implement SCBA best practices such as described by the minimum requirements outlined in NFPA 1404 Standard for Fire Service Respiratory Protection Training.18

The fire department had not instituted a respiratory or health and wellness program within its department. Members were provided basic training on the use of a SCBA but no respiratory fit testing was provided. The members had not been issued their own facepieces, but rather shared a universal facepiece assigned to each SCBA. Policies for facial grooming were not instituted by the department that could potentially affect the seal required for the facepiece to keep hazardous gases out. The development of a respiratory protection program is an integral part of an overall fire department’s safety and health program.

Recommendation #12: Fire departments should ensure that fire fighters are aware of the dangers involved in fighting mobile homes fires.

Discussion: Mobile homes present challenges to successful fireground operations because of the close proximity of external structures, small interior spaces, and lack of permanent water supplies inside mobile home parks.19 The materials used to finish the interior of a mobile home can include wood paneling, vinyl and other plastic floor coverings, carpeting, and low-density fiberboard ceilings, which are all highly combustible, and give off toxic gases and compounds such as formaldehyde, hydrogen cyanide, carbon monoxide, carbon dioxide, ammonia, and benzene. These combustible materials coupled with limited ventilation, small interior spaces (see Diagram 1), conduction of heat from the home’s metal frame and exterior siding, and central hallway acting like a horizontal chimney can increase fire progression and make conditions prime for a potential flashover.b Other concerns while fighting a mobile home fire may include deteriorating floor members, noncode-compliant additions, pitched or aesthetic roofs built over the existing flat metal roof, and cylinders of liquefied petroleum gas (LPG).

Fire departments should consider preplanning firefighting operations at mobile home parks in their response areas and provide this information to mutual aid departments. They should plan for sources of water, overhead electrical hazards, storage of LPG cylinders, accessibility, lot numbers, and additions to mobile homes. Fire departments should also develop SOPs on size-up, search and rescue, and fire attack for mobile homes due to potential hazards to fire fighters. And finally, fire departments should train fire fighters on the hazards involved in mobile home fires.

b The vinyl and resin particle board construction found in mobile homes increases the production of volatile vapors which can accelerate the production of an explosive fuel-to-air ratio much faster than in larger homes with different construction, thus bringing a room to flashover more quickly.20

Recommendation #13: Fire departments should ensure that policies and procedures for proper inspection, use, and maintenance of self-contained breathing apparatus (SCBA) are implemented to ensure they function properly when needed.

Discussion: NFPA 1981 Standard on Open-Circuit Self-Contained Breathing Apparatus for Emergency Services and NFPA 1852 Standard on Selection, Care, and Maintenance of Open-Circuit Self-Contained Breathing Apparatus speak directly to the maintenance and use of self-contained breathing apparatus.21,22 The fire department had not established a preventative maintenance program for their SCBAs. Annual maintenance, testing, and repairs require an individual to receive specialized training from factory-certified technicians and to perform required tasks as outlined by the manufacturer. This requires special tools, equipment, and knowledge to take apart the components of a SCBA, which are normally not available to a fire department. Daily, weekly, and or monthly inspections of a SCBA needs to be documented to include items like air cylinder and remote pressure gauge readings, general state of SCBA components and face piece, PASS device actuation, and regulator flow test and hydrostatic tests. A documented inspection can catch minor issues before they result in a SCBA malfunction or failure.

The victims’ facepieces had not been flow tested since 2002, and the SCBAs did not meet the current edition of NFPA 1981. The face piece used by victim #2 was missing a harness anchor screw which could affect the seal of the mask. Also, the victims’ air packs did not contain an integrated or stand-alone PASS device. Fire fighters need to know and officers need to reinforce that a SCBA is an integral part of fire fighters’ protective clothing, and without it they cannot safely enter hazardous environments requiring respiratory protection. Preventative maintenance programs are designed to extend the life of a product and catch potentially life-threatening problems.

REFERENCES

- IFSTA [2008]. Essentials of fire fighting. 5th ed. Stillwater, OK: Fire Protection Publications, International Fire Service Training Association.

- Klinoff R [2003]. Introduction to fire protection. 2nd ed. Clifton Park, NY: Thomas Delmar Learning.

- Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA). 29 CFR 1910. 134 Respiratory Protectionexternal icon. [https://www.osha.gov/pls/oshaweb/owadisp.show_document?p_table=STANDARDS&p_id=12716]. Date accessed: September 2009.

- Baud FJ, Barriot P, Toffis V, et al [1991]: “Elevated blood cyanide concentrations in victims of smoke inhalation.” New England Journal of Medicine. 325:1761–1766.

- Silverman SH, Purdue GF, Hunt JL, et al [1988]: “Cyanide toxicity in burned patients.” Journal of Trauma. 28(2):171–176.

- Gagliano M, Phillips C, Jose P, Bernocco S [2008]. Air management for the fire service. Tulsa, OK: Penn Well Corporation.

- Wallace D [1990]. In the mouth of the dragon: toxic fire in the age of plastics. New York, NY: Avery Publishing Group.

- Friedman R [1998]. Principles of fire protection chemistry and physics. Quincy, MA: National Fire Protection Association.

- NFPA [2007]. NFPA 1500 Standard on fire department occupational safety and health program. 2007 ed. Quincy, MA: National Fire Protection Association.

- NFPA [2008]. NFPA 1561 Standard on emergency services incident management system. 2008 ed. Quincy, MA: National Fire Protection Association.

- IFSTA [1998]. Fire department company officer. 3rd ed. Stillwater, OK: Fire Protection Publications, International Fire Service Training Association.

- NFPA [2008]. NFPA 1521 Standard for fire department safety officer. 2008 ed. Quincy, MA: National Fire Protection Association.

- IFSTA [1994]. Fire service ventilation. 7th ed. Stillwater, OK: Fire Protection Publications, International Fire Service Training Association.

- NIOSH [1994]. NIOSH Alert: preventing injuries and deaths of fire fighters. Cincinnati, OH: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, DHHS (NIOSH) Publication No. 94-125 [https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/fire.html].

- NFPA [2004]. NFPA 1720 Standard for the organization and deployment of fire suppression operations, emergency medical operations, and special operations to the public by volunteer fire departments. 2004 ed. Quincy, MA: National Fire Protection Association.

- Dodson D [2007]. Fire department incident safety officer. 2nd ed. New York: Thomson Delmar Learning.

- NFPA [2007]. NFPA 1971 Standard on protective ensembles for structural fire fighting and proximity fire fighting. 2007 ed. Quincy, MA: National Fire Protection Association.

- NFPA [2006]. NFPA 1404 Standard for fire service respiratory protection training. 2006 ed. Quincy, MA: National Fire Protection Association.

- Taylor J [2008]. Trailer fire tacticsexternal icon. Fire Engineering. [http://www.fireengineering.com/articles/2008/05/trailer-fire-tactics.html]. Date accessed: September 2009. (Link Updated 1/17/2013)

- Davie B [1988]. The investigation of mobile home fires. The National Fire and Arson Report. 6(4).

- NFPA [2007]. NFPA 1981 Standard on open-circuit self-contained breathing apparatus (SCBA) for emergency services. 2007 ed. Quincy, MA. National Fire Protection Association.

- NFPA [2008]. NFPA 1852 Standard on selection, care, and maintenance of open-circuit self-contained breathing apparatus (SCBA). 2008 ed. Quincy, MA. National Fire Protection Association.

INVESTIGATOR INFORMATION

This investigation was conducted by Stacy C. Wertman and Jay Tarley, Safety and Occupational Health Specialists, and Tim Merinar, Safety Engineer with the Fire Fighter Fatality Investigation and Prevention Program, Fatality Investigations Team, Surveillance and Field Investigations Branch, Division of Safety Research, NIOSH located in Morgantown, WV. This report was authored by Stacy C. Wertman. A technical review was provided by Division Chief W. Edward Buchanan. Vance Kochenderfer, NIOSH Quality Assurance Specialist, National Personal Protective Technology Laboratory, conducted an evaluation of the victims’ self-contained breathing apparatus.

Special thanks to the staff of the West Virginia Fire Commission, Office of the State Fire Marshal and the West Virginia University Fire Service Extension for their assistance during this investigation.

Diagram 2. Incident scene when evacuation alarm sounded and location of victims when found.

APPENDIX

Status Investigation Summary of Two

Self-Contained Breathing Apparatus

NIOSH Task Number 16263

Background

As part of the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) Fire Fighter Fatality Investigation and Prevention Program, the Technology Evaluation Branch agreed to examine and evaluate two Scott Air-Pak Fifty 4.5, 4500 psi, 30-minute, self-contained breathing apparatus (SCBA).

This SCBA status investigation was assigned NIOSH Task Number 16263. The West Virginia Fire Commission was advised that NIOSH would provide a written report of the inspections and any applicable test results.

The SCBA, contained within a corrugated cardboard box, were delivered to the NIOSH facility in Bruceton, Pennsylvania on March 25, 2009. After its arrival, the package was taken to building 108 and stored under lock until the time of the evaluation.

SCBA Inspection

The package was opened in the Firefighter SCBA Evaluation Lab (building 02) and a complete visual inspection conducted on May 26, 2009 by Eric Welsh, Engineering Technician, NPPTL. The first SCBA inspected was designated as Unit #1. The second, designated Unit #2, was opened and inspected that same day. The SCBA were examined, component by component, in the condition as received to determine their conformance to the NIOSH-approved configuration. The visual inspection process was video recorded. The SCBA were identified as the Scott Air-Pak Fifty 4.5 models.

Both units have suffered heat damage. This is prevalent on the rearward-facing portions of the SCBA such as the cylinder and waist belt fabric. In contrast, forward-facing components such as the facepiece and shoulder straps generally do not show signs of excessive heat exposure. Labels on the regulators of both units seem to indicate they were last flow-tested in 2002. The nose cup in the Unit #1 facepiece is missing an inhalation valve and is not secured to one of the speech diaphragm tubes. While this would not compromise the respiratory protection provided, it could contribute to fogging of the lens or carbon dioxide buildup in the facepiece. The heat damage to this unit, particularly the high-pressure hose, prevented it from being tested. One of the head harness attachment point studs of Unit #2 is missing. It is impossible to tell from this examination when this occurred, although it does not appear to have been the result of excessive pull force on the head harness strap as the attachment hole in the fabric is not distorted.

The Beacon Alarm remaining service life indicator appears to be damaged and did not function at all during the evaluation. It was judged that this unit could be safely pressurized and tested using a substitute facepiece and cylinder.

SCBA Testing

The purpose of the testing was to determine the SCBA’s conformance to the approval performance requirements of Title 42, Code of Federal Regulations, Part 84 (42 CFR 84). Further testing was conducted to provide an indication of the SCBA’s conformance to the National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) Air Flow Performance requirements of NFPA 1981, Standard on Open-Circuit Self-Contained Breathing Apparatus for the Fire Service, 1997 Edition.

NIOSH SCBA Certification Tests (in accordance with the performance requirements of 42 CFR 84):

- Positive Pressure Test [§ 84.70(a)(2)(ii)]

- Rated Service Time Test (duration) [§ 84.95]

- Static Pressure Test [§ 84.91(d)]

- Gas Flow Test [§ 84.93]

- Exhalation Resistance Test [§ 84.91(c)]

- Remaining Service Life Indicator Test (low-air alarm) [§ 84.83(f)]

National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) Tests (in accordance with NFPA 1981,

1997 Edition):

- Air Flow Performance Test [Chapter 5, 5-1.1]

Unit #2 was tested on July 2, 2009 using a substitute facepiece and cylinder. All testing was video recorded with the exception of the Exhalation Resistance Test and Static Pressure Test. The SCBA failed to meet the requirements of the NFPA Air Flow Performance Test. This was a result of the Beacon Alarm failing to activate during testing, which may have been caused by damage or depletion of the batteries. Had the Beacon Alarm operated properly, the unit would have met the requirements of all tests.

Summary and Conclusions

Two SCBA were submitted to NIOSH by the West Virginia Fire Commission for evaluation. The SCBA were delivered to NIOSH on March 25, 2009 and inspected on May 26, 2009. The units were identified as Scott Air-Pak Fifty 4.5, 4500 psi, 30-minute, SCBA (NIOSH approval number TC-13F-76). Both units have suffered heat exposure, with Unit #1 exhibiting somewhat greater damage. The Beacon Alarm on Unit #2 did not function. One head harness attachment stud on the Unit #2 facepiece was missing. Only Unit #2 was judged to be in a condition safe for testing, with the use of a substitute cylinder and facepiece. Testing was conducted on July 2, 2009. As a result of the SCBA’s Beacon Alarm not operating, it failed to meet the requirements of the NFPA Air Flow Performance Test. Unit #2 passed all other testing. No maintenance or repair work was performed on the units at any time. In light of the information obtained during this investigation, NIOSH has proposed no further action on its part at this time. Following inspection and testing, the SCBA were returned to storage pending return to the West Virginia Fire Commission. If the units are to be placed back in service, they must be repaired, tested, and inspected by a qualified service technician. The cylinders of both units are damaged beyond repair and should be condemned and disposed of. Labels on both units seem to indicate they were last flow-tested in 2002; the fire department must conduct such testing and other maintenance activities following the schedule prescribed by the SCBA manufacturer. Typically a flow test is required on at least an annual basis.

|

The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH), an institute within the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), is the federal agency responsible for conducting research and making recommendations for the prevention of work-related injury and illness. In fiscal year 1998, the Congress appropriated funds to NIOSH to conduct a fire fighter initiative. NIOSH initiated the Fire Fighter Fatality Investigation and Prevention Program to examine deaths of fire fighters in the line of duty so that fire departments, fire fighters, fire service organizations, safety experts and researchers could learn from these incidents. The primary goal of these investigations is for NIOSH to make recommendations to prevent similar occurrences. These NIOSH investigations are intended to reduce or prevent future fire fighter deaths and are completely separate from the rulemaking, enforcement and inspection activities of any other federal or state agency. Under its program, NIOSH investigators interview persons with knowledge of the incident and review available records to develop a description of the conditions and circumstances leading to the deaths in order to provide a context for the agency’s recommendations. The NIOSH summary of these conditions and circumstances in its reports is not intended as a legal statement of facts. This summary, as well as the conclusions and recommendations made by NIOSH, should not be used for the purpose of litigation or the adjudication of any claim. For further information, visit the program website at www.cdc.gov/niosh/fire or call toll free 1-800-CDC-INFO (1-800-232-4636).

|

This page was last updated on 11/3/09.