Two Volunteer Fire Fighters Die Fighting a Basement Fire - Illinois

Death in the Line of Duty…A summary of a NIOSH fire fighter fatality investigation

Death in the Line of Duty…A summary of a NIOSH fire fighter fatality investigation

F2001-08 Date Released: July 31, 2002

SUMMARY

On February 17, 2001, a 29-year-old male volunteer Lieutenant (Victim #1) and a 32-year-old male volunteer fire fighter (Victim #2) died while fighting a basement fire. Both victims were part of a crew searching for fire extension when they were suddenly surrounded by intense heat and fire. Upon the crew’s exit of the structure, it was discovered that the two victims did not exit. The Incident Commander (IC) ordered additional fire fighters to enter the basement and search for the victims. After extensive rescue efforts, both victims were removed from the structure and transported to a nearby hospital where they were pronounced dead.

NIOSH investigators conclude that, to minimize the risk of similar occurrences, fire departments should

- ensure standard operating procedures (SOPs) addressing emergency scene operations such as basement fires are developed and followed on the fireground

- ensure that Incident Command (IC) conducts a complete size-up of the incident before initiating fire-fighting efforts and continually evaluates the risk versus gain during operations

- ensure adequate ventilation is established when attacking basement fires

- ensure that accountability for all personnel at the fire scene is maintained

- ensure that a Rapid Intervention Team is in place before conditions become unsafe

- ensure that a separate Incident Safety Officer (ISO), independent from the Incident Commander, is appointed

INTRODUCTION

On February 17, 2001, a 29-year-old male volunteer Lieutenant (Victim #1) and a 32-year-old male volunteer fire fighter (Victim #2) died while fighting a basement fire. On February 24, 2001, the U.S. Fire Administration notified the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) of this incident. On March 17, 2001, two Safety and Occupational Health Specialists and the Team Leader of NIOSH’s Fire Fighter Fatality Investigation and Prevention Program investigated this incident. Meetings and interviews were conducted with the Chief, Assistant Chief, and fire fighters who were at the scene, and with the regional representative from the State Fire Marshal’s office. Investigators reviewed the victim’s training records, autopsy reports, photographs of the incident scene, fire department witness statements, and a transcription of the dispatch tapes. The incident site was visited and photographed.

The volunteer fire department involved in this incident is comprised of 23 fire fighters. The department serves a population of approximately 2,500 in a geographical area of 89 square miles. The department requires all new fire fighters to complete training on the following: hazmat, apparatus operation, live fire training, search and rescue, and first aid. The State of Illinois does not require their volunteer fire fighters to obtain a certain level of training. Victim #1 was Fire Fighter Level II-certified, and he was an Emergency Medical Technician (EMT). He had 5 years of fire-fighting experience, including 9 months as a Lieutenant. Victim #2 was certified as a Fire Fighter Level I, as an EMT [emergency medical technicians] and as a driver operator, and he had 2 years of fire-fighting experience.

The structure involved in this incident was a single-story, brick-veneer ranch with a full basement. The State Fire and Arson Bureau declared the fire accidental and its origin to be in the southeast section of the basement in an electrical panel. Additional mutual-aid departments responded to this incident; however, only those directly involved are included in this report.

INVESTIGATION

On February 17, 2001, at approximately 0800 hours, the owner of a single-family home noticed smoke in the area of the first-floor bathroom. She called a family member to investigate the cause of the smoke; however, nothing was found. When they could not find any reason for the smoke, the resident called Central Dispatch. Central Dispatch notified the volunteer fire department of a basement fire at 0817 hours. The following apparatus responded:

Engine 1 (with the Chief, a Captain [Pump operator], and three fire fighters)

Engine 7 (the Assistant Chief, a Lieutenant [Victim #1] and three fire fighters [including Victim #2])

Ambulance 15 (two fire fighters/EMTs)

Ambulance 23 (a Captain and four fire fighters/EMTs)

A fire fighter and a Lieutenant responded by privately owned vehicles (POVs).

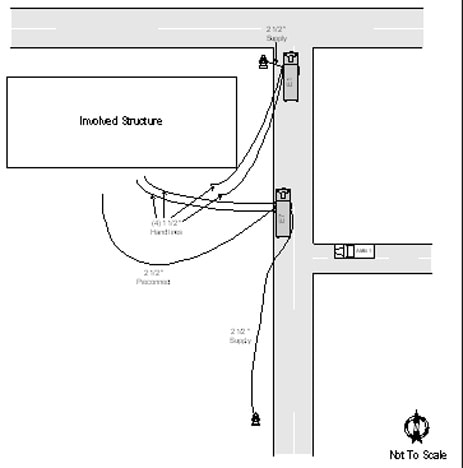

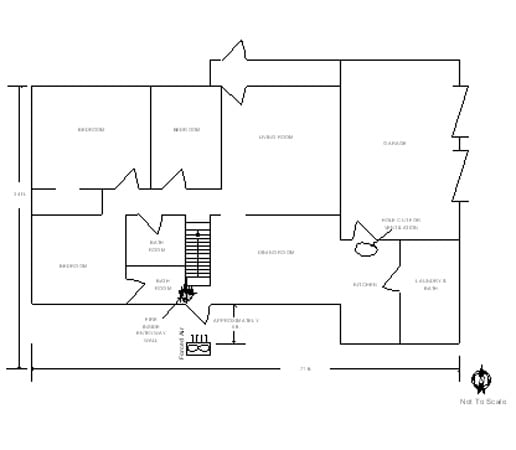

At 0823 hours, Engine 1 and Ambulance 15 were the first to arrive on the scene. When approaching the scene, the crew noticed a small amount of white smoke emitting from the house. Fire fighters from Engine 1 pulled two 1½-inch preconnects and stretched both lines to the south door of the structure (Diagram 1). The Chief assumed Incident Command (IC) and was informed by a relative of the resident that no one was inside the structure and that the resident had noticed smoke in the bathroom on the first floor (Diagram 2). Engine 7 and Ambulance 23 arrived on the scene at 0824 hours. While Engine 7 connected their supply line to a hydrant and pulled a 1½-inch preconnect to the south side of the structure, the Assistant Chief conducted a scene size-up while walking around the structure. He noticed light gray smoke emitting from the eaves and around the chimney with no visible flames. The Chief informed the Assistant Chief they had two 1½-inch lines pulled to the south (rear) door.

The IC sent a Captain, two fire fighters and Victim #2 to the roof to provide ventilation. Two fire fighters from Engine 1 entered the south side of the structure with a 1½-inch hoseline, and a second 1½-inch hoseline was in place for backup. While searching for the location of the fire, the crew noted that the smoke was thick, brown, and banked to the floor. Scattered throughout the home were large amounts of furnishings and debris, which hindered fire fighters’ efforts during the entire attack. The two fire fighters continued their search; however, they could not find any visible fire. They found no fire on the first floor and began to back out of the structure, taking the nozzle with them. On the way out, part of the dining room ceiling collapsed (Diagram 2), and fire began rolling out of the collapsed area. They opened the nozzle and extinguished all visible fire in the area of the collapse.

When they exited the structure, they reported the conditions they had encountered to the Assistant Chief and explained that they thought the fire was located in the attic. The ventilation crew was informed that they had an attic fire, and they made a second ventilation hole in the roof. The ventilation crew observed light smoke after the cuts were made.

At approximately 0848, the IC requested Central Dispatch to tone out a mutual-aid department to provide a pumper with additional crews. At approximately 0853 hours, the IC requested a second mutual-aid department to provide an air cascade unit and a Lieutenant from his department to fill air bottles.

A crew was sent into the south entrance to pull ceiling tile and insulation in the dining room area. During this time, a fire fighter set up a positive pressure ventilation fan (PPV) at the south entrance door. The crew found and extinguished fire inside the left wall of the entryway to the basement. The fire was exposed under the sill plate of the wall in the entryway adjacent to the stairs as a fire fighter leaned against the wall (Diagram 2). This led the Assistant Chief to believe they had a basement fire. The Chief used a thermal imaging camera (TIC) in the garage area to check for heat but did not find any.

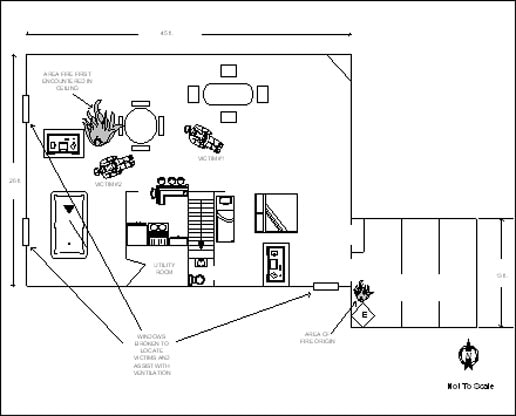

Victim #1 and two other fire fighters entered the south-side door to make the first entry into the basement. The crew took a 1½-inch hoseline with them. At the foot of the stairs, they saw fire on the ceiling to the west (Diagram 3). The crew opened the nozzle and pushed the fire back. One of the fire fighters left the basement to retrieve halogen lights and flashlights and to inform the Assistant Chief that they had a working basement fire. With one low air alarm sounding, the crew exited the basement after knocking down the fire. A fire fighter and Victim #1 then vented two basement windows on the west side of the basement to relieve smoke and heat.

On the second entry into the basement, the crews encountered light fire to the west and quickly knocked it down. The Assistant Chief assigned the Captain, Victim #2, and another fire fighter as the backup crew on standby. When the two fire fighters conducting the basement search exited the structure, they reported no visible fire, just smoke and heat.

The Assistant Chief sent the Captain and his crew into the basement for a third entry. The Captain was on the nozzle followed by Victim #2 and another fire fighter. Victim #1 also entered the structure at this time. The crew made their way toward the southwest, noticing light smoke, but they did not see any flames. Victim #2 sprayed the ceiling where the Captain had pulled ceiling tile. The Chief instructed a fire fighter, staged at the south-side door, to take the TIC to the crew in the basement. He followed the hoseline down to the crew in the basement, passing the TIC to another fire fighter. The crew made their way to the northeast, just beyond the stairwell (Diagram 3). The Captain and other fire fighters continued to use the TIC, looking for hot spots. At approximately this time, the Lieutenant arrived with additional air bottles in his (POV). Once on the scene, the Lieutenant noticed light white smoke coming from the structure. Between 0857 and 0920 hours, four engines from a mutual-aid department responded to the scene to provide an air cascade unit, equipment, and additional personnel.

The Captain, facing north, heard a fire fighter yell “fire.” The heat was immediate, piercing through his Nomex® hood on the left side of his face. The Captain dropped to his knees and instructed his crew to get out of the basement. The entire east side of the basement, including the stairwell, was engulfed in flames. The Captain crawled up the stairs with one fire fighter following. The Lieutenant heard a noise near the south door and saw a fire fighter coming out of the structure with smoke coming off his coat. Thick black smoke and flames were coming out of the south doorway. At about the same time, the Assistant Chief began to conduct another size-up when he heard glass break and saw thick, black smoke rolling from the south-side door. Once the Captain was out of the structure, the Assistant Chief approached him and asked who else was in the basement. The Captain told him the only one who was not out of the structure was Victim #2. NOTE: At that time, the Captain did not realize Victim #1 was also in the basement. At about this time, the Chief from the mutual-aid department arrived and noticed heavy black smoke coming from the south-side door and the garage area.

The Assistant Chief instructed a crew to pull a 2½-inch preconnected hoseline from Engine 7 and advance it to the south door, spraying water into the house. The crew shut down the nozzle and vented all the north-side windows. This crew vented the floor over the fire just inside the door leading from the garage in an attempt to achieve vertical ventilation. At this time, the Assistant Chief was notified that Victim #1 was still in the structure. The Assistant Chief made radio contact with Victim #1, asking if he knew his location. Victim #1 replied that he did not know his location and that he was running low on air. Rescue attempts were hindered due to the extreme heat, smoke, and flames. The Chief from the mutual-aid department ordered a crew to vent the roof. He was notified that there were already two cuts to the roof; however, the Chief instructed the crew to make additional ventilation cuts. After assigning a ventilation crew, the Chief pulled an additional line into place for backup. At that time he noticed a problem with water pressure because the supply line was kinked in two places.

The Lieutenant took a 1½-inch hoseline into the basement to search for the victims. He made his way approximately halfway down the steps, then realized he did not inform anyone of this entry. He retreated to get help. After the Chief from the mutual-aid department straightened the supply line, there were no further problems with the water pressure. At approximately 0914 hours, the Chief requested advance life support from a neighboring department and two Lifeflight helicopters from Central Dispatch.

The Lieutenant and a fire fighter from the mutual-aid department followed the 1½-inch hoseline (taken into the basement by the Captain and his crew) into the basement to attempt to rescue the victims. The rescue crew heard a personal alert safety system (PASS) device sounding. They followed the PASS and found Victim #2 approximately 8 feet to the west of the basement steps. He was lying on his side with his helmet off and Nomex® hood partially off. They could also hear Victim #1’s PASS device sounding in the same area where Victim #2 was located. The crew was able to pull Victim #2 to the base of the stairs; however, they could not lift him up the steps. They crawled back to the top of the stairs and reported that they had found Victim # 2. After changing their air bottles and obtaining some rope, they reentered with another fire fighter and the Chief from the mutual-aid department to remove Victim #2. Victim #2 was removed from the structure, loaded onto a backboard, and taken via ambulance to the helicopter landing zone. A second rescue crew entered the basement. They located Victim #1 approximately 6 feet north from the base of the stairs and used rope to assist in removal. Victim #1 was loaded onto a backboard and taken by ambulance to the helicopter landing. Victim #1 and Victim #2 were both taken via helicopter to the local hospital where they were pronounced dead.

CAUSE OF DEATH

According to the autopsy report, the cause of death for both Victim #1 and Victim #2 was asphyxiation caused by inhalation of products of combustion.

RECOMMENDATIONS/DISCUSSION

Recommendation #1: Fire departments should ensure standard operating procedures (SOPs) addressing emergency scene operations, such as basement fires, are developed and followed on the fireground. 1, 2, 3, 4

Discussion: Standard operating procedures (SOPs) should be developed addressing emergency-scene operations. The SOPs for emergency operations should cover specific operations such as ventilation, water supplies, motor vehicle fires, and basement fires. Basement fires present a complex set of circumstances, and it is important that SOPs are developed and followed to minimize the risk of serious injury to fire fighters. The SOPs should be in written form and be included in the overall risk management plan for the fire department. If these procedures are changed, appropriate training should be provided to all affected members. The department involved in this incident did not have SOPs available at the time of the investigation.

Recommendation #2: Fire departments should ensure that Incident Command (IC) conducts an initial size-up of the incident before initiating fire-fighting efforts and continually evaluates the risk versus gain during operations at an incident. 2, 3, 5

Discussion: A proper size-up begins from the moment the alarm is received, and it continues until the fire is under control. Interior size-up is just as important as exterior size-up. Since the IC is staged at the command post (outside), the interior conditions should be communicated as soon as possible to the IC. One of the most important size-up duties of the first-in officers is locating the fire and determining its severity. This information lays the foundation for the entire operation. It determines the number of fire fighters and the amount of apparatus and equipment needed to control the blaze. Size-up also assists in determining the most effective point of fire extinguishment attack and the most effective method of venting heat and smoke. Interior conditions could change the IC’s strategy or tactics. In this incident, heavy smoke was emitting from the exterior roof system, but fire fighters could not immediately find any fire in the interior. While searching for fire in the attic, it was discovered that the fire was actually in the basement.

Recommendation #3: Fire departments should ensure adequate ventilation is established when attacking basement fires. 3

Discussion: Heat and smoke from basement fires quickly spread upward into the building in the absence of built-in vents. To reduce vertical extension, direct ventilation of the basement during fire attack is necessary. This can be accomplished in several ways. Horizontal ventilation can be employed to vent heat, smoke, and gases through wall openings such as doors and windows even if the windows are belowground-level in wells. Natural pathways such as stairways can also be used to vent the basement area provided the means used to ventilate the heat and smoke do not place other portions of the building in danger. As a last resort, the basement can be vented by cutting a hole in the floor near a ground-level opening such as a door or window. The heat and smoke can then be forced from the basement through the exterior opening using mechanical ventilation.

Recommendation #4: Fire departments should ensure that accountability for all personnel at the fire scene is maintained. 6, 7, 8

Discussion: Accountability on the fireground is paramount and may be accomplished by several methods. It is the responsibility of all officers to account for every fire fighter assigned to their company and relay this information to Incident Command (IC). Fire fighters should not work beyond the sight or sound of the supervising officer unless equipped with a portable radio. Communication with the supervising officer by portable radio should be maintained to ensure accountability and indicate completion of assignments and duties. One of the most important aids for accountability at an incident is an Incident Management System (IMS). The IMS is a management tool that defines the roles and responsibilities of all units responding to an incident. It enables one individual to have better control of the incident scene. This system works on an understanding among the crew that the person in charge will be “standing back” from the incident, focusing on the entire scene. With an accountability system in place, the IC may readily identify the location of all fire fighters on the fireground. Additionally, the IC would be able to initiate rescue within minutes of realizing a fire fighter is trapped or missing.

Recommendation #5: Fire departments should ensure that a Rapid Intervention Team be in place before conditions become unsafe. 4

Discussion: A Rapid Intervention Team (RIT) should be positioned to respond to every major fire. The team should report to the officer in command and remain at the command post until an intervention is required to rescue a fire fighter(s). The RIT should have all the tools necessary to complete the job, e.g., a search rope, first-aid kit, and a resuscitator. Many fire fighters who die from smoke inhalation, from a flashover, or who are caught or trapped by fire, actually become disoriented and run out of air. The RIT should be positioned and ready to respond when a fire fighter(s) is down or in trouble. This RIT team should be comprised of fresh, well-rested fire fighters.

Recommendation #6: Fire departments should ensure that a separate Incident Safety Officer (ISO), independent from the Incident Commander, is appointed. 4, 6, 9, 10

Discussion: According to NFPA 1561, paragraph 4-1.1, “the Incident Commander (IC) shall be responsible for the overall coordination and direction of all activities at an incident. This shall include overall responsibility for the safety and health of all personnel and for other persons operating within the incident management system. While the IC is in overall command at the scene, certain functions must be delegated to ensure adequate scene management is accomplished.” According to NFPA 1500, paragraph 6-1.3, “as incidents escalate in size and complexity, the IC shall divide the incident into tactical-level management units and assign an ISO to assess the incident scene for hazards or potential hazards.” The most effective ISOs are those who operate as a consultant to the IC. The ISO establishes a relationship with the IC by asking what the action plan is, followed by a summary of the current situation status and resource status. With this information, the ISO can collect more information in the form of a reconnaissance or 360-degree size-up of the incident and report concerns and possible solutions to the IC. During this incident, the IC was also acting as the Safety Officer and thus was limited in being able to perform the additional functions of a separate ISO.

REFERENCES

- NFPA [1997]. Fire protection handbook. 18th ed. Quincy, MA: National Fire Protection Association.

- Brunacini AV [1985]. Fire command. Quincy, MA: National Fire Protection Association.

- International Fire Service Training Association. [1998]. Essentials of fire fighting. 4th ed. Stillwater, OK: Oklahoma State University.

- NFPA [1997]. NFPA 1500, standard on fire department occupational safety and health programs. Quincy, MA: National Fire Protection Association.

- Norman J [1998]. Fire officer’s handbook of tactics. Saddle Brook, NJ: Fire Engineering Books and Videos.

- NFPA [1995]. NFPA 1561, standard on fire department incident management system. Quincy, MA: National Fire Protection Association.

- Morris G, Gary P, Brunacini N, Whaley L [1994]. Fireground accountability: the Phoenix system. Fire Engineering, 147(4):45-61.

- Coleman [1997]. Incident management for the street smart fire officer. Saddle Brook, NJ: Fire Engineering Books and Videos.

- Smoke CH [1999]. Company officer. New York: Delmar Publishers.

- NFPA [1997]. NFPA 1521, standard for fire department safety officer. Quincy, MA: National Fire Protection Association.

INVESTIGATOR INFORMATION

This incident was investigated by Kimberly Cortez and Jay Tarley, Safety and Occupational Health Specialists, and Richard Braddee, Team Leader, Division of Safety Research, NIOSH.

Diagram 1. Apparatus Layout

Diagram 2. First Floor

Diagram 3. Basement

This page was last updated on 7/30/02