Flagger Killed When Struck by a Dump Truck, During Road Construction, in Washington State

|

|

Investigation: #99WA07001

Release Date: May 28, 2002

SUMMARY

On October 18, 1999, a 45-year-old female “flagger” died after being struck by a dump truck as it was backing up in a residential road construction site. The flagger (victim) was working with a construction company hired by the county to pave the residential street. The construction crew had already completed paving the west side of the street and was in the process of paving the east side when the incident occurred. The victim had been assigned to control traffic at a side street feeding the two-lane road being paved. Full and empty dump trucks were traveling through the work zone. A pilot car was used to bring non-road construction traffic up and down the west side of the road. As the pilot car approached the victim’s flagging position during one of its runs, the driver of the pilot car noticed that the victim was in the roadway and in the path of an on-coming dump truck. The dump truck was in the process of backing down the west side of the road to drop its load of asphalt into a paver. Its backup alarm was activated at the time. Shortly after being seen by the pilot car driver, she was struck and killed by the dump truck. Within moments of the incident, the local emergency medical rescue unit was called and arrived at the incident site, but the victim died at the scene of the incident.

To prevent future similar occurrences, the Washington State Fatality Assessment & Control Evaluation (FACE) investigative team concluded that flaggers involved in highway construction work zones should follow these guidelines/requirements:

- Flaggers should not put themselves at risk attempting to stop vehicles intruding into work zones.

- Employers need to have a continuing process for site and program evaluation and the identification, correction, and communication of hazardous conditions for workers within a changing work zone.

- Flaggers should be equipped with two-way portable radio communication devices and other emergency signaling equipment.

- Consider using a spotter to provide direction for trucks and heavy equipment backing up in work zones.

- Dump trucks should be equipped with additional mirrors or other devices to cover “blind spot” areas for drivers when they are backing up.

- Employers should develop methods to ensure that flaggers have adequate warning of equipment or vehicles approaching from behind.

- Employers should continually train all workers regarding specific hazards associated with moving construction vehicles and equipment within a work zone.

- Employers should develop and use an Internal Traffic Safety Plan (ITSP) for each highway and road work zone project.

INTRODUCTION

On October 18, 1999, the Washington State FACE Program was notified by the WISHA* (Washington Industrial Safety & Health Act) Services Division of the death of a 45-year-old female highway construction flagger.

The Washington FACE Principle Investigator and the Field Investigator met with the regional WISHA representatives who were investigating the case. After reviewing the case with WISHA, the WA FACE team traveled with the WISHA representatives to the incident site. The WISHA representative helped pinpoint the incident location, the road construction site details, and defined the position of the people and equipment involved in this incident.

The incident site was in a suburban residential neighborhood. The street being re-paved was a relatively wide two-lane arterial with a moderate traffic flow. The street measured 37 ft. 3 in. from curb-to-curb near the incident site. Traffic runs north and south along this street and has a mix of single-family homes and apartment complexes in the vicinity of the incident.

About two weeks prior to the incident date, the contractor had milled the road in preparation for paving. On October 15, 1999, the previous Friday, the contractor had paved the west side (south-bound lane) of the road. No work was conducted over the weekend.

The county agency responsible for this road had established a contract with a national construction company’s local representative to re-pave the ½-mile section of road through a normal bid/contract process, as part of their overlay program. The contractor was to follow a Traffic Control Plan (TCP) as defined by the county.

The company had been in business for over 40 years and had approximately 300 hundred employees working in the region and approximately 7,000 employees nation-wide. The company specializes in asphalt paving. Over it’s many years in business, the company had been involved in numerous paving projects in the state.

The company had a full time safety and health person in the region, but the individual was not at the construction site at the time of the incident. The company also had an active safety and health committee that met on a monthly basis. Job site crew and supervisors met prior to the start of their workday at each site to discuss the work to be done that day and safety issues. The company required and verified the use of certified flaggers and certified traffic control supervisors for highway and road projects needing to use flaggers for traffic control. They also had a written accident prevention program and a site-specific accident prevention program for this operation.

The victim, at the time of the incident, was working as part of a team of 10 flaggers and 2 traffic control supervisors on this project. The victim had previously worked at this site for only one day, a Friday prior to the incident.

The victim had been in the construction flagging profession for several years and had a current flagger certification card. She worked out of a local union hall and had previously worked for this same construction company on short duration jobs. The victim had also worked for a number of other construction companies and worked out of other union halls.

INVESTIGATION

On October 18, 1999, a Monday morning, a paving contractor was preparing to finish paving a section of road that had been started earlier that month in a residential area of Washington State.

The work started at approximately 7:00 AM when the paving contractor’s crew gathered to prepare for the day’s paving activities. Prior to the start of work, the contractor held a briefing with the paving employees and Traffic Control Supervisor (TCS) to discuss the work for the day. At another briefing the TCS met with the flaggers and discussed the day’s activities and their assignments.

Construction work signs were set up and other traffic control devices were placed in accordance with the project’s Traffic Control Plan (TCP) and Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices (MUTCD) 1 guidelines as well as the Washington State Department of Transportation guidelines.* Paving equipment was set up and other preparation work began. The flaggers took up their positions within the work zone.

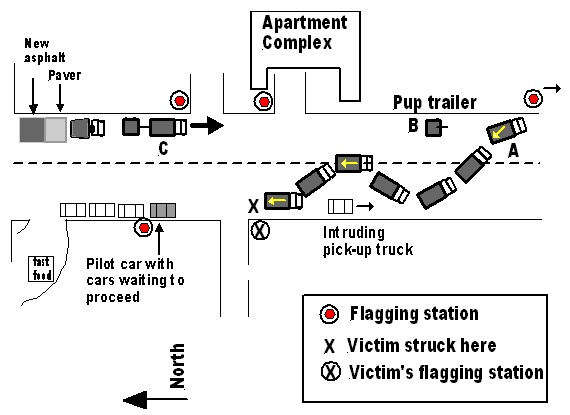

The flaggers were positioned at various points along the work zone for traffic control and worked in conjunction with a pilot car to manage traffic along the section of road being paved. One of the traffic control supervisors drove the pilot car. The flaggers who were stationed at the two work zone project entrance locations were equipped with two-way radios. The flaggers stationed along the work zone controlling street intersections and apartment complex driveways did not carry two-way radios (See figure 1).

The pilot car was being used to guide one-way traffic through the work zone and was equipped with a two-way radio so the driver could communicate with the two radio equipped flaggers and the paving project foreman. The pilot car was also equipped with a CB radio so it could communicate with the construction vehicles with CB radios and communicate beyond the work site.

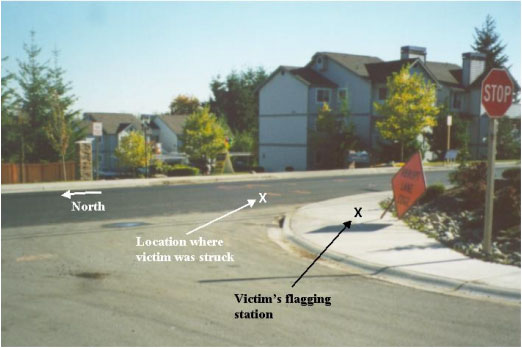

The victim had been assigned to control traffic from one of the intersections which lead to a cul-de-sac along the work zone, and to watch for traffic turning into and out of an apartment complex across the street (figure 2). The victim did not have a two-way radio.

Flaggers were instructed to hold vehicles at their positions until they could have them merge in behind the pilot car as it traveled up and down the traffic lane of the work zone.

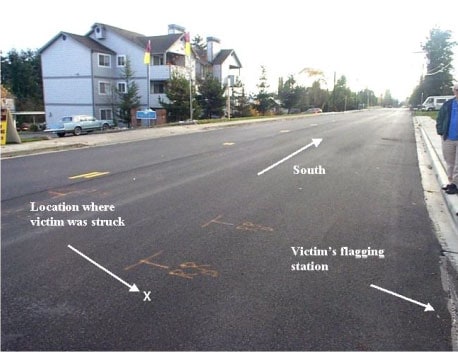

The section of street where the victim was standing was relatively level and visibility towards both ends of the work zone was good (figure 3). The weather was clear and dry. Witnesses stated that there was little or no wind and the truck’s back up alarms were very noticeable.

Paving started at approximately 7:30 AM that morning with the paving crew laying hot asphalt on the east side of the road. The contractor was using one of their own dump trucks and drivers, plus two other subcontracted dump trucks and drivers to shuttle asphalt to the paver.

At approximately 8:15 AM, a contract dump truck had been given the signal from the paving foreman to bring his load to the paver. He was driving a 19.8 ton Kenworth dump truck (A in figure 1) and had previously dumped a load from his pup trailer (B) and disconnected the trailer. He began backing up his truck to dump his load of asphalt. At about the same time that the dump truck was backing up, the pilot car was traveling toward the backing truck. The pilot car driver saw a white pick-up truck intruding into the work zone and called to warn the dump truck driver. The dump truck pulled into the east lane of the road to allow the pick-up truck to pass and then moved back to the lane of travel (the west lane) and continued to back up. Backing up in the west lane allowed an empty dump truck (C) to exit from the paver using the east lane (See figure 1).

While the dump truck backed up, the victim was seen in the traffic lane. She had, for an unknown reason, left her designated flagging position. It was estimated at first sighting, that she was between 3 to 4 car lengths directly behind the dump truck as it backed up towards her. Within moments, before anyone could warn her, she was struck and killed by the dump truck. The dump truck operator stated that he never saw the victim in his mirrors prior to striking her with his rear wheels.

It is not known why the victim had entered the work zone traffic lanes prior to her death. One of the more feasible theories is that she saw the pick-up truck enter the work zone and acted to prevent a collision. She may have communicated with or attempted to communicate with the pick-up truck’s driver, or she was attempting to communicate with the dump truck driver to avert a collision. Witnesses noted that they saw her looking at the backing dump truck and thought she would have been aware of its movement. Witnesses also clearly heard the back up alarm from the approaching dump truck.

The Washington State Patrol Commercial Vehicle Enforcement officers inspected the dump truck and found it to be in good working condition. It was estimated that the truck was backing up at a speed of between 5 and 8 mph.

The white pick-up truck drove out of the construction site without stopping or anyone getting its license number. The driver most likely did not see the incident nor was aware that the flagger had been struck by the dump truck.

CAUSE OF DEATH

The medical examiner listed the cause of death as cerebral lacerations with multiple skull fractures and multiple visceral lacerations due to crushing injury to the head and trunk.

RECOMMENDATIONS/DISCUSSION

Recommendation #1: Flaggers should not put themselves at risk attempting to stop vehicles intruding into work zones.

Discussion: Flaggers working in a road or highway construction work zone, have multiple responsibilities. The responsibilities include the safety of the general public, the construction vehicles and workers in the work zone, and most importantly for their own personal safety.

Recognized traffic control guidelines have basic principles for flagging operations that relate directly to the flagger’s physical position within the work zone.

- Never stand in the lane being used by moving traffic,

- Never turn your back to traffic,

- Never assume a vehicle is going to stop until it does, and

- Be sure that the driver sees you.

Flaggers should stand in a highly visible area along the shoulder or on a sidewalk out of the vehicle traffic lanes. The flagger should face oncoming traffic but be positioned so they are out of both the public traffic lane and the active work zone.

In this incident, there are several theories as to “why” the victim entered the work zone traffic lanes. Knowing the true reason for this would help us understand and prevent future incidents, but may also be immaterial. The flagger did not follow some of the guiding principles of the job and left her flagging station, went into the active traffic lane, and turned her back on traffic. She may have done so to prevent injury and physical damage to the vehicles that were converging on each other, but in doing so, she put herself at serious risk and paid for that risk with her life.

One of the most important responsibilities of the employer and the flagger is for the flagger’s own personal safety.

Recommendation #2: Employers need to have a continuing process for site and program evaluation and the identification, correction, and communication of hazardous conditions for workers within a changing work zone.

Discussion: A daily briefing should be conducted prior to each day’s work activity. The briefing should include a discussion of various elements of the job/site safety plan and a more detailed discussion of the plan of action for that day. If there are any changes made to the plan for the day’s activity, then everyone needs to be aware of those changes.

In addition, employers need to review safe flagging practices with flaggers on a routine basis. The Traffic Control Supervisor should meet with the paving foreman and the flaggers to review necessary information and to get a clear understanding of the type and extent of the work that is to be done that day and how the “moving” work zone will impact the safety of everyone working and traveling through the zone. There should be specific instruction that defines what to do in emergencies and in unexpected, non-routine situations, like the intrusion of a vehicle.

Before starting a flagging job the employer and flagger need to familiarize themselves with the work area and review known and potential hazards. They also need to review the changing aspects of a moving work zone. They should review communication and emergency warning practices. Review the practice of identifying a vehicle’s license number if it intrudes into the work zone or fails to follow the flagger’s signals. The flagger should not put themselves at risk trying to stop the vehicle. Instead they should sound whatever warning device the flagger has available and then report the vehicle to the traffic control supervisor, the paving foreman, the police, or to whomever the plan indicates can take appropriate corrective action.

Safety procedures should be developed for the work site and be enforced. Traffic control supervisors need to be knowledgeable of traffic control principles and how to apply them to site-specific work zone operations. If a hazardous situation is identified, then the job should be stopped until the situation is corrected.

The traffic control plan should periodically be evaluated, especially after an intrusion incident occurs, such as in this incident. Analysis of the program’s failure will allow for changes that can be implemented to prevent future intrusions.

Essentially the best practice is to expect the unexpected. It is important that all persons have the training, knowledge, and skills to address the potential hazards of flagging in a work zone.

Recommendation #3: Flaggers should be equipped with portable radio communication devices and other emergency signaling equipment.

Discussion: For many flaggers, the primary and sometimes only means of communication to vehicles passing through the work zone and to other construction workers in the work zone is through the use of hand signals and hand-held “stop and slow” paddles and/or flags.

The victim in this incident used hand signals and the “stop/slow” paddle to help direct traffic and communicate with motorists from her flagging station. The victim did not have a two-way radio or other emergency-signaling device to communicate with the construction workers or the traffic control supervisor. Only the flaggers at the main road entrances to the traffic work zone were equipped with two-way radios. The pilot car had both two-way and CB radios to communicate with the work zone entrance flaggers, project foreman, and construction vehicles.

In this incident several people saw the event taking place but did not have an effective mechanism to warn the flagger to get out of the way of the backing dump truck or to warn the truck driver of the presence of a worker on foot in the truck’s blind spot.

The requirements and general guidelines that apply to having flaggers equipped with radios vary in relation to the complexity of the work zone and the visibility between flagging positions. Some counties and cities specify requirements related to two-way radio use for flaggers. This job had no such requirements for the flagger.

In an active and volatile highway or road construction work zone, effective communication can be the most important safety element in the project. It is recommended that all flaggers be equipped with two-way radios so that they can not only interchange important information with the work site personnel but they can receive feedback or warnings to prevent injury or death. Many radios today have “hands free” capability, with an ear piece and collar mounted microphone which allow the user to have their hands free to perform their normal flagging duties. Spare batteries and radios should be made available or another warning system be used as a back up in case a radio fails. Cellular telephones can be used as communication devices, but they are not as instantaneous as radios and may be a potential distraction.

There are a variety of other warning devices that are also available on the market that could be used as well. Some simple devices are whistles or air-activated horns. While more complex systems can use an electronic device worn on the flagger’s belt, similar to a pager.

A Johns Hopkins University study indicated that a significant number of “backing up” injury incidents occurred when someone was watching, but unable to communicate with the truck driver or victim quickly enough to avert the incident.2

Recommendation #4: Consider using a spotter to provide direction for trucks and heavy equipment backing up in work zones.

Discussion: In highway and road construction it is a routine practice for large construction vehicles to continually move in and out of the work zone. When a truck backs up in a busy work zone there is a high risk of an incident or injury to either the driving public or pedestrian traffic and to construction vehicles and workers within the work zone. The highway/road construction work zone can be a very confined and congested space. Truck drivers and other equipment operators need to be observant and aware of activities, vehicles, and people that may interfere with their ability to safely complete their task.

One option to better manage trucks and other construction equipment backing up in the work zone is to use a spotter. A spotter can help the truck driver or equipment operator safely maneuver in and out of the work zone. The spotter provides the “vision” that the driver does not have when backing up and helps reduce their “blind spots”.

The construction work zone is a constantly changing arena and can change unexpectedly, as it did in this fatal incident. A spotter with proper precautions for their own personal safety can help the construction vehicle driver maneuver through these changing conditions, as well as help the flagger concentrate on the non-construction traffic traveling through the work zone.

|

Notes for Using a Spotter When using a spotter, it is of the utmost importance that the safety of the spotter be taken in consideration in the planning and application of the job.

|

Recommendation #5: Dump trucks should be equipped with additional mirrors or other devices to cover “blind spot” areas for drivers when they are backing up.

Discussion: The dump truck involved in this fatal incident was equipped with several relatively standard mirrors, but these mirrors did not provide the necessary vision for the driver to see the victim and stop the truck before backing over her. Both the right and left side mirrors consisted of a flat mirror with a convex mirror below. The truck also had an additional convex mirror mounted on the passenger side of the truck, which gave the driver visibility of the passenger step area. Although these mirrors provide adequate vision for the truck driver while he is backing, they were not enough to give the driver the complete picture of what was going on behind him. The dynamics of how these mirrors are situated and the basic elements of the design of a dump truck, still lead to “blind spots” for the driver’s vision.

There are several approaches that a truck owner or a truck leasing/rental company can take in providing better visual coverage for a driver when backing a truck.

One would be to consider the use of a “cross-view” mirror which is similar to those currently being used by delivery vans and the US Postal Service. These mirrors provide vision to the driver of the back of their truck. These mirrors may be difficult to adapt to all types of construction vehicles because of location/attachment problems and because of environmental exposures to the mirrors that can make management and maintenance of the mirrors difficult. The use of cross-view mirrors on construction vehicles deserves further study.

There are also a variety of other vision enhancement and object/people detection devices that could be used to help drivers when they are backing their vehicles in work zones. Some of this equipment includes radar, sonar and ultrasonic devices. Rear vision video cameras are also available that can provide the driver a clear view of what is behind them while backing. Many of these camera systems are currently in use in both construction and non-construction applications.3 NIOSH and the Washington State Department of Transportation are also currently evaluating a number of these systems.4

Construction traffic at work sites needs to be managed in such a manner as to protect the safety and well being of all personnel and equipment at the site.

Recommendation #6: Employers should develop methods to ensure that flaggers have adequate warning of equipment or vehicles approaching from behind.

Discussion: The flagger’s job often puts them in a very vulnerable and exposed position in relation to the vehicle traffic that they are assigned to control and guide through a traffic work zone. The victim in this incident had 270 degrees of exposure to vehicles.

The flagger has an equally serious exposure in the highway construction work zone, to construction vehicles and equipment. NIOSH statistics5 show that more workers are struck and seriously injured or killed by construction vehicles that are in the process of backing up within these work zones than for any other injury source.

Between 1992 and 1998, the Census of Fatal Occupational Injuries (CFOI)3 reported 841 worker fatalities in the SIC 1611, which is “Highway and Street Construction.” Of those fatalities, 492 occurred within the work zone and 465 of the 492 were vehicle or equipment related incidents. The majority of the incidents involved dump trucks backing over workers in the construction work zone.

In order to address the hazard of a construction vehicle backing over a flagger, or the possibility of a non-construction vehicle intruding into the work zone from behind the flagger, employers need to develop methods to ensure flaggers have adequate warning of a vehicle striking them from behind.

There is a variety of warning methods that could be used.

One is to consider the use of helmet mirrors such as the types used by bicyclists and snowmobilers. These units may be effective, but require the user to frequently check the mirror for on-coming traffic or to use them to scan the area behind them. The mirror may also distract the flagger from the task at hand.

A second method would be to use a second individual to act as a spotter for the flagger. The spotter is an extra set of eyes that can assist in effective traffic control and provide a warning for the flagger in the event of a vehicle approaching from behind the flagger. (Note: Placing additional workers on foot in a work zone is not an ideal situation, because they are also potentially exposed to vehicular and machinery traffic. The safety of the spotter must be taken in consideration when using this option).

A third method would be to use a device such as a motion sensor or intrusion detection system that could send a warning signal to the flagger when a vehicle is approaching from behind.

A fourth method is the use of a protective barrier such as a “jersey barrier”. This could isolate the flagger from traffic.

Recommendation #7: Employers should continually train all workers regarding specific hazards associated with moving construction vehicles and equipment within a work zone.

Discussion: Flagger training and education should be one of the top issues that an employer address when they hire or assign an individual to flagging duties at one of their work sites.

A flagger having a certification card is an important part of the employer’s knowledge that the flagger has had at least basic instruction regarding flagging duties, but it does not define the flagger’s experience and general knowledge of a wide variety of highway and road work zone situations. In Washington State, a flagger is required to be re-certified every three years. Certification is an excellent administrative safety control measure and having to re-certify every three years strengthens the process, but much can happen in three years.

Training for flaggers and other highway and road construction workers should extend beyond their initial training and certification processes. Providing job safety instruction, training, and education for workers needs to be a continuing process.

Training is especially important for people working in high hazard industry jobs such as in highway and road construction. Errors in judgment or improperly evaluating and responding to a change in the operation or an emergency can have serious consequences that result in injury and death. An example of this is highlighted by this report’s incident when the pick-up truck made a potentially unauthorized entry into the work zone.

A training and education process should include industry-accepted flagger training guidelines and reinforce flagger best practices, and provide for review of current safety and health regulatory requirements for the job. Practices to avoid construction vehicles while they back up in the work zone should be identified and safe flagging guidelines stressed.

The employer should make routine inspections of the work site and make corrections and changes to the work zone process and their internal safety and training plans as necessary.

Recommendation #8: Employers should develop and use an Internal Traffic Safety Plan (ITSP) for each highway and road work zone project.

Discussion: In our earlier discussion regarding highway and road construction work zone hazards, we have noted that there are both external and internal hazards that need to be addressed when trying to manage a safe and productive work zone.

A “Traffic Control Plan” (TCP) primarily addresses traffic controls to be used to facilitate pedestrian and non-construction vehicles’ safe passage through the temporary highway and road construction work areas.

In order to address internal construction work zone hazards, it is recommended that an ITSP be developed for each construction site. In developing an ITSP, many of the same issues considered for a TCP should be considered for an ITSP.

The elements of the ITSP should indicate where and how construction equipment, vehicles, and workers on foot interact within the work zone. The plan must also take into consideration the changing aspects of a work site.

It is important that the safety plan be clearly understood by all workers. The plan should define the work areas, hazards, and other potential emergency situations relating to the construction work zone. Good planning is important to managing a safe operation.

Highway work zone traffic control safety has been an area of concern for both Washington State and the nation for many years. Statistics have shown that fatalities in highway and road construction work zones have been increasing over time.

Flaggers have a potentially hazardous, yet highly responsible position to play in the temporary traffic control process. The safety of workers, motorists, and pedestrians are closely interdependent on the flagger’s abilities, training and education, and their judgment in dealing with a variety of traffic situations.

Training and certification is a good step in helping prevent serious injury and fatalities to flaggers, but these elements are only part of the solution. In order to prevent serious incidents involving flaggers, one needs to take more of a systems approach to reduce the risks to flaggers. These approaches need to incorporate greater responsibility by employers and contractors in the planning and management of highway and road construction projects. The plans need to encompass the safety elements of both external and internal traffic control. They need to incorporate better communication and emergency signaling devices and blend in other new technology that can reduce the risks involved with flagging in highway and road construction work zones.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

In conducting the Flagger Fatality Investigation, the Washington State FACE Investigation Program requested that the contents of this report be reviewed by key representatives from labor and the highway and road construction industry, private consultants, and Washington State and Federal agencies.

Though we are not able to acknowledge specific individuals for their invaluable input into this document, we would like to recognize the following for their help and support to the FACE investigation process:

- The Employer involved in the incident

- WISHA enforcement

- WISHA Policy & Technical Services staff

- Federal Face Program Management (NIOSH)

- Safety & Health Assessment & Research for Prevention (SHARP)

- Local Council of Laborers

- Construction company safety director

- Washington State DOT

- Washington State Attorney Generals Office

References

- Federal Highway Administration’s: Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices (MUTCD), 1995 Edition-Revision 4, part VI, Standards and Guides for Traffic Controls for Street and Highway Construction, Maintenance, Utility, and Incident Management Operations, URL: http://mutcd.fhwa.dot.govexternal icon

- “Danger in the Highway Work Area”, Joint study by the Laborers’ Health Fund of North America, Laborers’ International Union of North America and the John’s Hopkins University, Federal Highway Administration, 1999.

- Trout, Nada D., Ullman, Gerald L., Devices and Technology to Improve Flagger/Worker Safety/Research Report 2963-1F. College Station Texas: The Texas Transportation Institute, The Texas A&M University, Texas Department of Transportation. 1997.

- “Selection of Systems to Monitor Blind Areas Behind Sanding Trucks”, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, Spokane Research Laboratory, Prepared for the Washington State Department of Transportation by Todd M. Ruff, October 30, 2000.

- “Building Safer Highway Work Zones: Measures to Prevent Worker Injuries From Vehicles and Equipment”, Pratt, SG, Fosbroke, DE, and Marsh, SM, Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, April 2001, DHHS (NIOSH) Publication No. 2001-128, URL: https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/docs/2001-128/ (Link updated 3/26/2013)

* The OSHA State Plan program in Washington State.

* The MUTCD gives guidance to contractors, municipalities, departments of transportation, etc. on the safe setup and operation of highway and road construction work zones.

Figure 1. Schematic of work zone and the incident.

Figure 2. Victim’s flagging post.

Figure 3. View flagger had towards the on-coming dump truck.

RESOURCES

- Part VI Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices (MUTCD), Part VI Standards and Guides for Traffic Controls for Street and Highway Construction, Maintenance, Utility and Incident Management Operations. 1988 Edition of MUTCD, Revision 3, September 1993 U.S Department of Transportation, Federal Highway Administration.

- Signaling and Flaggers, Chapter 296-155-305 WAC (Washington Administration Code), State of Washington, Department of Labor and Industries.

- Employee Protection in Public Work Areas, Chapter 296- 45-52530 WAC, State of Washington, Department of Labor and Industries.

- Pratt, Stephanie G., Fosbroke, David E., Marsh, Suzanne M. Building Safer Highway Work Zones: Measures to Prevent Worker Injuries From Vehicles and Equipment. Cincinnati, OH. National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, April 2001.

- Work Zone Traffic Control Guidelines. M54-44, Washington State Department of Transportation, Field Operations Support Center, May 2000.

- Danger In The Highway Work Area. Joint study by the Laborers’ Health Fund of North America, Laborers’ International Union of North America and the John’s Hopkins University. Federal Highway Administration, 1999.

- Flagger’s Certification Handbook: Third Edition. Seattle, WA: Evergreen Safety Council, 1999.

- Anderson, Roy W., editor, Training for Work Zone Safety, Trans. Safety Reporter, Volume V, No. 4, April 1987.

- Graham, Jerry L., Hinch, John, Stout, Dale, Lerner, Neil, Maintenance Work Zone Safety. Washington, DC: National Research Council, Strategic Highway Research Program, 1990.

- Traffic Control Plans. City of Kent Development Assistance Brochure, 6-5. Kent, WA, October 9, 2001.

- Highway Work Zone Safety. Washington State Department of Transportation, January 1994.

APPENDIX

Applicable Regulations

In reviewing the WISHA standards, there are defined requirements that deal with highway and road construction flagging operations. Although the investigation of this incident was not regulatory in nature, we offer the following code requirements for information and reference purposes. This is not intended to be a complete list of regulatory guidelines that address these issues:

Signaling and Flaggers. WAC 296-155-305

Except as otherwise required in these rules, traffic control devices, signs and barricades must be set up and used according to the guidelines and recommendations in the Federal Highway Administration’s: Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices (MUTCD), 1995 Edition-Revision 4, part VI, Standards and Guides for Traffic Controls for Street and Highway Construction, Maintenance, Utility, and Incident Management Operations.

WAC 296-155-305 (1)(a)

Flaggers are to be used only when other reasonable traffic control methods will not adequately control traffic in the work zone.

WAC 296-155-305 (2)(b)

While flagging during daylight hours, a flagger must, at a minimum, wear:

A high visibility safety garment designed according to Class 2 specifications in ANSI/ISEA 107-1999, American National Standard for High-Visibility Safety Apparel. Specifically, a garment containing at least 775 square inches of background material and 201 square inches of retroreflective material that encircles the torso and is placed to provide 360 degrees visibility around the flagger. The acceptable high visibility colors are fluorescent yellow-green, fluorescent orange-red or fluorescent red; and a high visibility hard hat. The acceptable high visibility colors are white, yellow, yellow-green, orange or red.

When snow or fog limit visibility, a flagger must wear pants of any high visibility color other than white.

WAC 296-155-305 (5) (a)

When it is not possible to position work zone flaggers so they are not exposed to traffic or equipment approaching them from behind, the employer, responsible contractor and/or project owner must develop and use a method to ensure that flaggers have adequate warning of such traffic and equipment approaching from behind the flagger.

Note: The following are some nonmandatory examples of methods that may be used to adequately warn flaggers:

Mount a mirror on the flagger’s hard hat.

Use a motion detector with an audible warning.

Use a spotter.

Use “jersey” barriers.

The department recognizes the importance of adequately trained flaggers and supports industry efforts to improve the quality of flagger training. However, training alone is not sufficient to comply with the statutory requirement of revised flagger safety standards to improve options available that ensure flagger safety and that flaggers have adequate visual warning of objects approaching from behind them.

Likewise, the department believes that standard backup alarms, which are already required on construction equipment, do not meet the intent of the legislature on this issue.

WAC 296-155-305 (8)

The employer, responsible contractor and/or project owner must conduct an orientation that familiarizes the flagger with the job site each time the flagger is assigned to a new project or when job site conditions change significantly. The orientation must include, but is not limited to:

- The flagger’s role and location on the job site;

- Motor vehicle and equipment in operation at the site;

- Job site traffic patterns;

- Communications and signals to be used between flaggers and equipment operators;

- On-foot escape route; and

- Other hazards specific to the job site.

WAC 296-155-305 (9) (a)

When flaggers are used on a job that will last more than one day, the employer, responsible contractor and/or project owner must keep on-site, a current site specific traffic control plan. The purpose of this plan is to help move traffic through or around the construction zone in a way that protects the safety of the traveling public, pedestrians and workers. The plan must include, but is not limited to, such items as the following when they are appropriate:

- Sign use and placement;

- Application and removal of pavement markings;

- Construction;

- Scheduling;

- Methods and devices for delineation and channelization;

- Placement and maintenance of devices;

- Placement of flaggers;

- Roadway lighting;

- Traffic regulations; and

- Surveillance and inspection.

WAC 296-155-305 (9) (b)

To contact Washington State FACE program personnel regarding State-based FACE reports, please use information listed on the Contact Sheet on the NIOSH FACE web site Please contact In-house FACE program personnel regarding In-house FACE reports and to gain assistance when State-FACE program personnel cannot be reached.

Back to Washington FACE reports

Back to NIOSH FACE Web