Female Firefighter Dies When Struck by an Out-of-Control Pickup Truck on an Icy Interstate Highway

Michigan Case Report: 06MI001

Summary

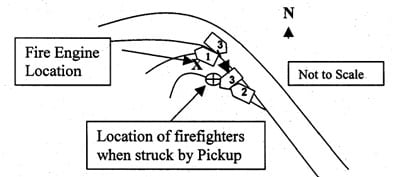

On January 7, 2006, a 34-year-old female firefighter was critically injured after being struck by a pickup truck that had lost control on an icy interstate highway. The fire department responded after being coded as a first call response by 911 dispatch that an accident had taken place on a local highway with occupants trapped. An engine was dispatched with three firefighters, the engine driver, lieutenant and the decedent. The incident occurred near a freeway entrance ramp. The entrance ramp was blocked by a car and pickup truck that had been involved in an accident at the ramp junction with the highway (Figure 1). The lieutenant and the decedent exited the engine and walked on the side of the freeway to the accident site while the engine driver repositioned the engine. As they were walking, a pickup lost control on black ice that had formed on the highway surface. The pickup slid out of control and struck the decedent. She was thrown off the highway shoulder onto the grass bank alongside the highway. Other emergency vehicles responded and she was transported to a local hospital. She died one week later from her injuries. After the incident, the fire department developed a standard operating procedure (SOP) for emergency response on roadways that incorporated the first four work practice recommendations listed in the RECOMMENDATIONS section of this report. The department’s SOP is attached as Appendix A.

|

|

Figure 1. Overview of incident site. |

Recommendations:

- Fire Departments develop, implement, and enforce standard operating procedures/guidelines (SOPs/SOGs) regarding emergency operations for roadway incidents and employees should receive training in the proper procedures and the hazards associated with emergency operations for highway incidents.

- Fire Departments ensure that firefighters establish a protected work area on roadways before safely turning their attention to the emergency.

- Fire Departments establish pre-incident plans regarding traffic control for emergency service incidents and pre-incident agreements with law enforcement and other agencies such as highway departments.

- Fire Departments ensure firefighters wear suitable high-visibility apparel meeting American National Standards Institute (ANSI) 107-2004 requirements when working as an emergency responder on a roadway.

- The State of Michigan should adopt a training module specific to operational practices in or near moving traffic as part of the Office of Fire Fighter Training firefighter training program.

- Michigan Department of Transportation (MDOT) should continue expanding the use of a “changeable message sign” to inform motorists of hazardous road conditions or vehicular accidents.

- The International Fire Service Training Association (IFSTA) should update the Fire Fighters Training Manual to include a chapter on emergency response vehicle positioning to protect emergency response workers.

Introduction

On January 7, 2006, a 34-year-old female firefighter was critically injured after being struck by a pickup truck that had lost control on an icy road. MIFACE was notified of the incident by a newspaper clipping. The fire department agreed to participate in May 2006. Since the initial acceptance, MIFACE has had many contacts with the fire department, including three visits to the fire department offices, speaking with one of the developers of the department’s Roadway Safety standard operating procedure at the MSU office, and attending a firefighter training program about positioning fire department response vehicles to protect personnel working in the incident scene area.

The decedent’s employer was a city fire department employing 90 individuals. The decedent’s job classification was firefighter. The department had been established about 100 years ago. The decedent worked full time. The work shift was one 24-hour day with two days off. Her shift began at 7:00 a.m. She had been employed by the fire department for seven years and was a member of the unionized workforce. The department had a written health and safety program, but at the time of the incident, did not have a standard operating procedure for conducting emergency response activities on a roadway.

During the writing of this report, MIFACE reviewed the death certificate, police report and pictures, 911 phone log, and medical examiners report.

Investigation

The decedent had arrived at work at 6:50 a.m. It had been raining, but not freezing rain. At approximately 7:00 a.m., 911 dispatch personnel notified the fire department to respond to a vehicle crash on the highway with occupants trapped. The engine driver indicated that when the windshield wipers were activated, the rain was freezing on the windshield.

The roadway involved in the incident was an unlighted two-lane highway with a median separating traffic moving in the opposite direction. The speed limit was 70 mph. The area of highway where the incident occurred was a blind curve for traffic moving eastbound. There was a light drizzle that began to freeze upon contact with the road. The road conditions had turned from being wet to “black ice” in a manner of minutes.

Multiple vehicular accidents had been reported due to the icy conditions. As vehicles traveling eastbound came around the curve, the drivers would see the multiple crashes ahead and would attempt to slow down or turn to avoid the accident vehicles. As the drivers would slow down or turn, they lost control of their vehicles and “spun out” and/or crashed into the median. Although an exact count is unknown, newspaper reports indicated that at least 13 crashes in the area were reported.

All vehicles described below were heading eastbound. Crash #1 (Figure 2, #1) involved a car (Car #1) that had attempted to slow down for another vehicle that was permitting a semi-truck to change lanes. When the driver of Car #1 tapped the vehicle brakes, the driver lost control and struck the rear bumper of a semi-truck. Car #1 came to a stop facing westbound on the right lane shoulder and partially on the entrance ramp used by the fire department to access the highway.

Crash #2 involved a Pickup truck #1 and Car #1 (Figure 2, #2). The driver of Pickup #1 came around the curve and lost control on the curve as he attempted to avoid another vehicle and struck Car #1. Pickup #1 was located to the east of Car #1, also facing westbound on the lane for the entrance ramp just east of the entrance ramp.

Crash #3 occurred when the driver of Car #2, which was traveling in the right lane, came around the curve and noticed the crash of Car #1 and Pickup #1 As the driver of Car #2 began to move from the right lane to the left lane, the driver lost control and spun out. The rear of the Car #2 struck the median wall and stopped. The driver exited the vehicle, walked across the roadway to a wooded area away from the road, and called 911.

Crash #4 involved another car (Car #3) and a pickup truck (Pickup #2). The driver of Pickup #2 struck Car #3. The driver of Pickup #2 was able to pull off to the shoulder and he exited the vehicle. He ran westbound down the eastbound road shoulder waving a flashlight to warn oncoming traffic about the conditions ahead.

The fire engine arrived at the scene. A city police vehicle came very shortly after the fire engine arrival. The fire engine driver parked the engine near the end of the ramp that was partially blocked by Car #1 (Figure 2, Box 1 and Letter X). All of the firefighters were dressed in the traditional turnout gear and duty helmets. The condition of the turnout gear worn at the site was unknown. Turnout gear observed by MIFACE at the time of the site visit to the decedent’s fire station was in good condition; the turnout gear was clean and the reflective stripes were visible with little apparent wear. The lieutenant and the decedent exited the fire engine and checked on the status of the driver of Car #1. The engine driver got out of the truck to start the generator for the parapet lights. After ascertaining that the driver of Car #1 did not need medical attention, the lieutenant and the decedent walked down the ramp near the concrete edge of the roadway near the rumble strips and onto the right shoulder of the highway to check on the status of the driver of Pickup #1 (Figure 2, Box 2). The lieutenant was nearest to the shoulder edge. The lieutenant was in a twelve o’clock position and the decedent was in a ten o’clock position as they approached Pickup #1. As they were walking, the lieutenant instructed the engine operator to move the fire engine to another location to assist in blocking off the scene. The engine’s emergency lights were activated.

|

|

Figure 2. Line Drawing of Incident Scene

|

Pickup Truck #3 (Figure 2, Box 3) was the vehicle that struck the decedent. As the lieutenant and the decedent walked on the road shoulder toward Pickup #1, the driver of Pickup #3 tapped his brakes in response to a vehicle ahead of him that had tapped its brakes. When driver of Pickup #3 tapped his brakes, the rear driver side of his vehicle began to fishtail and the vehicle began to slide towards the median wall. The vehicle struck the median wall and vehicle began to spin across the lanes of traffic toward the right highway shoulder and Pickup #1. As the decedent and lieutenant were walking toward Pickup #1, the engine driver entered the truck. She had her hand on the gearshift when she saw in her peripheral vision, Pickup #3 sliding toward the shoulder. The lieutenant saw the oncoming out-of-control truck and grabbed the decedent by the arm and told her to run. The lieutenant was able to get clear of Pickup #3 but the decedent was unable to get clear. She was struck by Pickup #3, landing on the hood and then on the ground. The decedent was thrown into the grassy area. Her helmet was found a short distance away. Pickup #3 came to rest on the grassy area of the shoulder facing southbound. The driver of Car #2 reached the decedent first and asked if she was ok. The decedent was unresponsive. The lieutenant arrived and then yelled to the engine operator to call for more help and to bring the oxygen. As the lieutenant and the engine operator were providing CPR, other emergency response vehicles arrived, and the decedent was transported to a local hospital where she died a week later from her injuries.

Back to Top

Cause of Death

The cause of death as listed on the death certificate was brain trauma. Toxicology was not performed.

Back to Top

Recommendations/Discussion

Fire departments develop, implement, and enforce standard operating procedures/guidelines (SOPs/SOGs) regarding emergency operations for roadway incidents and employees should receive training in the proper procedures and the hazards associated with emergency operations for highway incidents.

Emergency responders themselves are at risk of falling victim to “secondary incidents” that occur as they attend to the original incident to which they are dispatched. Firefighters operating at the scene of a motor-vehicle incident on a highway are in danger of being struck by oncoming motor vehicles. Department standard operating procedures/guidelines (SOPs/SOGs) can help establish proper traffic control measures when operating at an incident scene. SOPs/SOGs should include, but not be limited to, the following: parking on the same side of the roadway as the incident, apparatus positioning, lane closures, methods to establish a secure work area, clearing traffic lanes, releasing the incident scene back to normal operation, and wearing appropriate protective clothing at all times including the use of high-visibility reflective apparel when operating in or near moving traffic. As recommended in Protecting Emergency Responders on the Highways, “standard operating procedures (SOPs) should guide vehicle positioning upon arrival as an integral part of traffic control. Procedures should be scalable to incidents of varying size, magnitude, and location so as to be easily adapted to any sort of incident.” An example of a SOP for Safe Positioning While Operating In or Near Moving Traffic for fire departments is available at the Emergency Responder Safety Institute websiteexternal icon. http://www.respondersafety.com/default.aspx. (Link updated 4/1/2013)

The US Department of Transportation, Federal Highway Administration, Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices (MUTCD), Chapter 6I, Control of Traffic Through Traffic Incident Management Areas contains recommended practices for the management of traffic through locations effected by emergency road user occurrences, natural disasters, and other unplanned traffic interruptions. The 2003 revision, dated November 2004, is the most currently available revision of the MUTCD. Michigan adopted the federal 2003 MUTCD with a 2005 Michigan Supplement and Change list (Michigan Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices (MMUTCD)). The supplement addresses those items in the Michigan Vehicle Code that conflict with the 2003 Federal MUTCD and Special Items unique to Michigan.

MMUTCD Chapter 6I contains five sections. Section 6I.01 contains general information and guidance about temporary traffic control. Recommendations included within this section include that on-scene responders should be trained in safe practices for accomplishing their tasks in and near traffic. Responders should always be aware of their visibility to oncoming traffic and take measures to move the traffic incident as far off the traveled roadway as possible or to provide for appropriate warning. Responders arriving at a traffic incident should, within 15 minutes of arrival on-scene, estimate the magnitude of the traffic incident, the expected time duration of the traffic incident, and the expected vehicle queue length, and then should set up the appropriate temporary traffic controls for these estimates.

Firefighters who respond to highway incidents have numerous responsibilities, ranging from traffic control to assisting injured or stranded motorists. Responders must be trained to safely conduct multiple tasks near moving traffic. Because of the variability of each incident, all emergency responders should have ongoing, appropriate, task-specific training.

Fire departments ensure that firefighters establish a protected work area on roadways before safely turning their attention to the emergency.

Some of the most dangerous scenarios faced by firefighters are operations on highways, interstates, turnpikes, and other busy roadways. As stated in NFPA 1451 (8.1.4.1), “fire service vehicles shall be utilized as a shield from oncoming traffic wherever possible.” Placement of the first arriving fire apparatus should protect the scene by providing a work area protected from traffic approaching in at least one direction. Fire apparatus should be placed between the flow of traffic and the firefighters working on the incident to act as a shield. The apparatus should be parked on an angle so that the operator is protected by the tailboard. Front wheels should be turned away from the firefighters working highway incidents so that the apparatus will not be driven into them if struck from behind. Also consider parking additional apparatus 150 to 200 feet behind the shielding apparatus to act as an additional barrier between firefighters and the flow of traffic.” The positioning of apparatus (as a shield) is referred to as a “block” that creates a protected area known as the “shadow.” For limited-access, high-volume highway incidents, the first arriving apparatus (preferably a ladder truck or other large apparatus establishes the “block” by positioning the apparatus) upstream as the traffic approaches the scene from the incident, providing a “shadow” where emergency personnel can safely work. Emergency personnel should never leave the “shadow” for any reason.

Appendix A contains the standard operating procedure developed by the fire department after the incident for responding on a roadway. MIFACE has removed the department identifiers. MIFACE recommends that the fire department change the SOP to the requirement for Class III vests. Vehicular speeds in the area may very well exceed 50 mph. ANSI recommends Class III for areas that meet or exceed 50 mph.

Fire departments establish pre-incident plans regarding traffic control for emergency service incidents and pre-incident agreements with law enforcement and other agencies such as highway departments.

MMUTCD Chapter 6I, Section 6I.01 also states “In order to reduce response time for traffic incidents, highway agencies, appropriate public safety agencies (law enforcement, fire and rescue, emergency communications, emergency medical, and other emergency management), and private sector responders (towing and recovery and hazardous materials contractors) should mutually plan for occurrences of traffic incidents along the major and heavily traveled highway and street system.” Sections 6I02-6I.04 provide these agencies support and guidance for temporary traffic control for major, intermediate and minor traffic incidents. The last section, 6I.05 gives information of the use of emergency vehicle lighting.

According to NFPA 502, fire protection requirements for limited access highways include recommendations that “a designated authority shall carry out a complete and coordinated program of fire protection that shall include written preplanned emergency response procedures and standard operating procedures.” NFPA 1620 provides guidance to assist departments in establishing pre-incident plans. Pre-incident planning that includes agreements formed by a coalition of all involved parties such as mutual aid fire departments, EMS companies, police, and highway departments may save valuable time, present a coordinated response, and provide a safer emergency work zone.

The need to identify areas that have higher rates of incidents (e.g., motor vehicle crashes) should be evaluated so that standard operating procedures for emergency personnel can be tailored to the needs of particular sites (e.g., blind curves or corners, hills or sloped areas, and high-traffic areas). Fire departments can work with local highway departments and local law enforcement agencies to identify problem areas and devise solutions to those problem areas in advance. Experience and knowledge of local territory will help in creating pre-incident plans and in the establishment of standard operating procedures to make the response more efficient and safer for emergency responders.

Fire Departments ensure firefighters wear suitable high-visibility apparel meeting American National Standards Institute (ANSI) 107-2004 requirements when working as an emergency responder on a roadway.

Firefighters are routinely exposed to the hazards of low visibility while on the job. NFPA 1500, Standard for Fire Department Occupational Safety and Health Programs, Chapter 7.1.2 states “Protective clothing and protective equipment shall be used whenever the member is exposed or potentially exposed to the hazards for which it is provided.” The need to wear personal protective clothing such as a reflective, brightly colored vest arises from the fact that personnel need to be highly visible while working at the scene of a motor vehicle incident or while directing or blocking traffic near an incident scene.

The American National Standards Institute (ANSI) and the International Safety Equipment Association (ISEA) have published the ANSI/ISEA 107-2004 standard, which specifies different classes of high visibility safety garments based on wearer’s activities. This standard was developed in response to workers who are exposed to low visibility conditions in hazardous work zones. ANSI/ISEA have also recently published the ANSI/ISEA 207-2006 Standard for High-Visibility Public Safety Vests which establishes design, performance specifications and use criteria for highly visible vests that are used by law enforcement, emergency responders, fire officials, and DOT personnel. Both standards are voluntary, but they do provide employers consistent, authoritative guidelines for the selection and use of high-visibility apparel in the United States.

ANSI/ISEA 107-2004 is a voluntary standard that offers performance specifications for reflective materials, including minimum amounts, placement, background material, test methods and care labeling. The standard establishes three performance classes for high-visibility safety apparel based on the wearer’s activities, and determined by the total area of background and reflective materials used.

The standard will only affect the Law Enforcement, Emergency Responders, Fire Officials, and DOT Personnel sectors. It will improve the safety in multi-agency incidents by improving visibility and identification. It will reduce confusion and enhance communication between agencies. Basic vest requirements will include:

- Vest Dimensions

- Color: (Red for Fire Officials), (Blue for Law Enforcement), (Green for Emergency Responders), and (Orange for DOT Officials)

- Material Performance

- Special design features for users in fire, emergency medical, and law enforcement

- Higher Visibility (checkered color coded reflective trim)

The primary distinction of ANSI 207 versus ANSI 107 lies in the amount of fluorescent background material. ANSI 207 requires a minimum of 450 in2. This would fall between ANSI 107 Class 1 (217 in2) and Class II (775 in2) garments. The minimum amount of required retroreflective area (207 in2) did not change from ANSI 107 and 207. The difference in fluorescent material allow for design accommodation of equipment belts and for flexibility to incorporate colored panels to enhance easy, on-scene identification of wearers.

MIFACE recommends that fire departments conduct a survey of worksite low visibility hazards to determine the appropriate class of garments. Factors to consider are worker exposure to speed hazards, weather conditions, worker proximity to traffic, task loads and the traffic control plan. Class III garments provide the highest level of visibility to workers in high-risk environments that involve high task loads, a wide range of weather conditions and traffic exceeding 50 mph. Class III garments can provide coverage to the arms and/or legs as well as the torso, and can include pants, jackets, coveralls or rain wear. The standard recommends these garments for all roadway construction personnel and vehicle operators, utility workers, survey crews, emergency responders, railway workers and accident site investigators. These garments will assist approaching motorists to identify workers from a distance of approximately 1,280 feet.

When the safety apparel is issued, employers should ensure that employees receive training that explains the purpose and use of their new high-visibility garments.

The State of Michigan should adopt a training module specific to operational practices in or near moving traffic as part of the Office of Fire Fighter Training firefighters training program.

According to their website, the Office of Fire Fighter Training (OFFT) serves the training and certification needs of the State’s 1,075 fire departments and 30,672 firefighters and officers. The office prepares and publishes training standards, establishes courses of study, certifies instructors, establishes regional training centers, cooperates with State, federal, and local fire agencies to facilitate training of firefighters, and develops and administers mandatory certification examinations for new firefighters. The OFFT offers a Fire Fighter I and Fire Fighter II certification. Currently, no course is offered on how to position vehicles in an emergency response situation on a roadway to protect the incident scene from motorist or other incursions.

Within the Fire Fighters I and II curriculum are training modules specific to Michigan. These Michigan modules are referenced as M1 through M5, and are specially written modules that the state has adopted. The state could adopt a Michigan Module 6 that could include information on operational practices in or near moving traffic.

Michigan also has a program on apparatus driving. They have adopted the Volunteer Fire Insurance Services’ (VFIS) driver training/certification program. This program address inspection, driving and response considerations, but the program does not contain training on parking or operating in the roadway. The VFIS could modify their program, or a Michigan Module could be written and adopted into this program. This course is taken by those firefighters that want to drive apparatus, and would not be delivered to everyone.

Also on the OFFT website is a category of Health and Safety. A program could be written for the state and adopted by them and included in the list of Health and Safety programs that they endorse. The State does have precedent for adopting a program written by a Michigan Fire Department. The State has adopted two programs on Vehicle Extrication that were written by a Fire Chief from a Michigan County.

Michigan Department of Transportation (MDOT) should continue expanding the use of a “changeable message sign” to inform motorists of hazardous road conditions or vehicular accidents.

The need for this sign arises from the fact that this particular section of the highway is known to be hazardous during and after wet weather conditions. The sign would be permanently installed, spanning over the interstate, and the message would be controlled from the Emergency Operations Center (EOC). Two signs would need to be installed, one for each direction of the interstate. The message would be updated remotely on a real-time basis by the EOC when incidents are reported to them which have occurred on the interstate beyond the signs location. This would inform motorists of hazardous conditions or vehicular incidents ahead. The need to identify areas that have higher rates of automobile incidents should be evaluated so that standard operating procedures for emergency personnel can be tailored to the needs of particular sites (e.g., blind curves or corners, hills or sloped areas, and high traffic areas). Fire departments can work with local highway departments to identify trouble areas and devise solutions to those problem areas.

International Fire Service Training Association (IFSTA) should update the Fire Fighters Training Manual to include a chapter on emergency response vehicle positioning to protect emergency response workers.

Unfortunately, the IFSTA manual, which is utilized in the Michigan Fire Fighters Training Program, does not contain a chapter on emergency response vehicle positioning to protect the emergency response workers at the scene. Many firefighters and other emergency response personnel have been injured or killed because they were not protected from oncoming traffic. Because the IFSTA manual is extensively used in firefighter training programs across the United States, MIFACE encourages the IFSTA to develop a chapter on this subject matter.

References

MIOSHA standardsexternal icon cited in this report may be found at and downloaded from the MIOSHA, Michigan Department of Labor and Economic Growth (DLEG) website at: www.michigan.gov/mioshastandards. MIOSHA standards are available for a fee by writing to: Michigan Department of Labor and Economic Growth, MIOSHA Standards Section, P.O. Box 30643, Lansing, Michigan 48909-8143 or calling (517) 322-1845.

- NFPA [2002]. NFPA1451, standard for a fire service vehicle operations training program. Quincy, MA: National Fire Protection Association.

- University of Extrication “Safe Parking” SOP: safe positioning while operating in or near moving trafficexternal icon. (Link updated 4/1/2013) Responder Safety website: www.respondersafety.com/default.aspx. Safe Parking SOP: www.myfirecompanies.com/filelock/h19836034741146682747.doc (Link no longer available 3/25/2013)

- Phoenix Fire Department. M.P. 205.07A 04/95-R, standard operating procedures for safe parking while operating in or near vehicle traffic; M.P. 205.15 12/98R, freeway response; M.P. 202-16 06/97R, vehicle fires. Phoenix, AZ: Phoenix Fire Department.

- NIOSH [2001]. NIOSH Hazard ID 12: Traffic Hazards to Fire Fighters While Working Along Roadways. Cincinnati, OH: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, DHHS (NIOSH) Publication No. 2001-143.

- International Fire Service Training Association [1999]. Pumping apparatus driver/operator handbook. Stillwater, OK: Oklahoma State University.

- NFPA [2001]. NFPA 502, standard for road tunnels, bridges, and other limited access highways. Quincy, MA: National Fire Protection Association.

- Cohen HS, ed. [1999]. Cumberland Valley Volunteer Firemen’s Association, A White Paper: protecting emergency responders on the highways. Emmitsburg, MD: U.S. Fire Administration.

- NFPA [1998]. NFPA 1620, standard on recommended practice for pre-incident planning. Quincy, MA: National Fire Protection Association.

- NFPA [1997]. NFPA 1500, standard on fire department occupational safety and health program. Quincy, MA: National Fire Protection Association

- NIOSH Fire Fighter Fatality Investigation and Prevention Program. Internet Address: https://www.cdc.gov/Niosh/fire/

- ANSI/ISEA 107-2004 American National Standard for High Visibility Safety Apparel

- ANSI/ISEA 207-2006 American National Standard for High-Visibility Safety Vests

- EZ Facts – High Visibility Safety Apparelexternal icon. Document 153. Lab Safety Supply. Internet Address: http://www.grainger.com/content/qt-153-high-visibility-clothing?currenturl=%2FGrainger%2Fstatic%2Fhigh-visibility-clothing-standards-153.html&r=l&cm_mmc=LabSafety-_-Integration-_-AllPages-_-AllPages (Link updated 11/12/2013)

- Michigan Department of Transportation. 2005 Michigan Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices, 2003 Federal Edition, Chapter 6I, Control of Traffic Through Traffic Incident Management Areas. Internet Address: http://mdotwas1.mdot.state.mi.us/public/tands/plans.cfm (Link no longer available 4/9/2015)

- US Department of Transportation, Federal Highway Administration, Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices (MUTCD), Chapter 6I, Control of Traffic Through Traffic Incident Management Areasexternal icon. Internet Address: http://mutcd.fhwa.dot.gov/HTM/2003r1/part6/part6i.htm

Appendix

MIFACE Investigation Report # 06MI001 Appendixpdf iconexternal icon (see page 13 of report)

Michigan FACE Program

MIFACE (Michigan Fatality Assessment and Control Evaluation), Michigan State University (MSU) Occupational & Environmental Medicineexternal icon, 117 West Fee Hall, East Lansing, Michigan 48824-1315; http://www.oem.msu.edu/MiFACE_Program.aspx. This information is for educational purposes only. This MIFACE report becomes public property upon publication and may be printed verbatim with credit to MSU. Reprinting cannot be used to endorse or advertise a commercial product or company. All rights reserved. MSU is an affirmative-action, equal opportunity employer. 8/30/07 (Link updated 8/5/2009)

MIFACE Investigation Report # 06MI001 Evaluationpdf iconexternal icon (see page 12 of report)

To contact Michigan State FACE program personnel regarding State-based FACE reports, please use information listed on the Contact Sheet on the NIOSH FACE web site Please contact In-house FACE program personnel regarding In-house FACE reports and to gain assistance when State-FACE program personnel cannot be reached.