Dockworker Dies Due to Carbon Monoxide Poisoning While Using a Gasoline Powered Pressure Washer to Clean Inside a Freshwater Tank - Massachusetts

Massachusetts Case Report: 06-MA-045

Release Date: March 11, 2010

Summary

On November 9, 2006, a 38 year old dock worker (the victim) died from carbon monoxide poisoning, as he was pressure washing a freshwater tank on a fishing vessel. Five additional dockworkers sustained exposures to carbon monoxide in rescue attempts, and seven fire, police and emergency medical personnel were also exposed. The gasoline-powered pressure washer was placed below deck at the opening for the freshwater tank. The victim was overcome while pressure washing inside the tank. Two co-workers found the victim inside the tank and climbed in and pulled the victim out of the tank, but remained below deck. The two co-workers started to administer cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) and a bystander placed a call for emergency assistance. The local police and fire departments and emergency medical services all responded to the incident site. The victim, four co-workers, four firefighters and one police officer were transported to various local hospitals. The victim was pronounced dead at the local hospital where he was transported. The Massachusetts Fatality Assessment and Control Evaluation (FACE) Project concluded that to prevent similar occurrences in the future, employers should:

- Ensure that fuel-burning pressure washers are placed outdoors during operation and that carbon monoxide detectors are placed between the pressure washer and workers; and

- Develop, implement, and enforce a confined space entry program, as part of a comprehensive health and safety program.

Employers of first responders should:

- Develop procedures for rescuing victims in enclosed spaces with hazardous atmospheres.

Retailers, distributors and rental agents for fuel burning equipment, such as pressure washers, should:

- Affix a carbon monoxide (CO) warning label to equipment and provide customers with a CO fact sheet.

Manufacturers of fuel-burning pressure washers should:

- Affix a warning label about the hazards of carbon monoxide on their equipment; and

- Develop and promote fuel-burning equipment that emits low levels of carbon monoxide.

Background

Carbon monoxide (CO) is a poisonous, colorless, odorless and tasteless gas produced by burning fuel, such as gasoline, kerosene, oil, propane, coal or wood. When fuel-burning equipment, tools and appliances are used in enclosed spaces, or spaces without good ventilation, CO levels can accumulate quickly and can result in death.

CO is extremely hazardous because it deprives the body of oxygen and reaches deadly levels without being detected.1 Unintentional, non-fire-related CO poisonings account for an estimated 500 deaths and 15,000 – 40,000 emergency department visits in the United States annually.2 From 2002 through 2005, the Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC) noted 253 non-fire CO fatalities specifically associated with engine-driven tools.3

Since the early 1990s numerous incidents have resulted in warnings about gasoline pressure washers. In 1993, the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health issued a warning about indoor use of gasoline pressure washers, noting five incidents including one fatality of a farmer using a pressure washer in an enclosed barn.4 In 1994, five workers were overcome by carbon monoxide while using two pressure washers to clean an underground garage in Washington, DC.5 A study by the state of Washington found pressure washers among the dozens of sources of equipment responsible for work-related CO poisoning.6

Introduction

On November 9, 2006, the Massachusetts FACE Program was alerted by local media that earlier that same day a dock worker was overcome by carbon monoxide (CO). An investigation was immediately initiated. On November 20, 2006, the Massachusetts FACE Program Director and an assistant traveled to a wharf on the Massachusetts coast, where the vessel involved in the incident was docked, and met with the vessel owner and a marine safety consultant, hired by the vessel owner, to discuss the incident. The death certificate, police report, emergency medical service report, and the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) fatality and catastrophe report were reviewed.

In addition to the vessel involved in the incident, the company owned twenty-one other fishing vessels as well as fish processing and distribution plants. The victim had worked intermittently for the company over the previous four years. There were seven other employees that held the same job title as the victim: dockside maintenance worker. On the day of the incident, six of the eight dockside maintenance workers were working onsite. The employer stated that all of the employees were experienced dock workers who had worked for the company and other vessel owners at the fishing piers. The victim and other crew members usually worked about ten hours per day, six days per week, for a total of 55-60 hours each week. The Friday before the incident, the victim had been designated a full-time employee with the company, instead of an independent contractor as he had previously been employed. At the time of the incident, the victim’s supervisor was an independent contractor.

The company provided informal on-the-job training, which did not include health and safety topics. The victim was from Cape Verde, had been in the country for five years at the time of the incident, and spoke and read Portuguese. Since the victim, supervisor and the company owner all spoke Portuguese, they never used English when communicating with each other. It was not known if the victim spoke or read English.

Investigation

On the day of the incident, the victim had been assigned to clean the fresh water holding tank for a 90-foot steel hulled fishing vessel that was purchased two weeks prior to the incident (Figure 1). The vessel was being rigged as an offshore scalloper, which includes installation of steel towing dredges that are dragged along the sea bottom to collect scallops. The vessel was docked at a wharf at the time of the incident.

Scallopers spend several weeks at sea and, therefore must transport drinking water as well as fresh water for showers, cleaning dishes and cooking while on scalloping trips. It was reported that the vessel’s fresh water tank held 20,000 gallons of freshwater and that freshwater tanks are typically pressure-washed once every one to two years.

The freshwater tank was located below the foredeck, the forward part of the vessel below the main deck. It was accessed from the main deck by descending a narrow, steep ten-foot steel vertical fixed ladder down to the lower deck auxiliary engine room. This room provided access to the Captain’s sleeping quarters, main engine room and fish holds toward the stern of the vessel and the water tank toward the bow, or front of the vessel. The portal to the water tank was a small round opening, approximately 22.5 inches in diameter, located approximately four feet above the floor level of the lower deck (Figure 2).

It was reported by the marine safety consultant hired by the owner that the usual method of cleaning a freshwater tank was to place the gasoline-powered pressure washer on the main deck and run the hose down the ladder and into the fresh water tank through the portal. A worker would climb inside the fresh water tank and direct hot water, under pressure, at the surfaces of the fresh water tank.

The pressure washer that the company owned and usually used had a 100-foot hose, which allowed the pressure washer’s gasoline powered engine to remain on the main deck out in the open air, while the worker was inside the freshwater tank holding the nozzle end of the water hose. On this occasion, the company-owned pressure washer was reported to be broken. To accomplish the tank cleaning task, the crew rented a one cylinder gasoline-powered pressure washer from a local hardware store. The hose of the rented pressure washer was approximately 15 feet long, too short to station the pressure washer on the deck of the vessel while bringing the nozzle to the lower deck. Therefore, the crew brought the washer below, into the auxiliary engine room, and positioned it at the base of the ladder just outside the portal to the water tank. At the time of the incident the victim was working alone inside the freshwater tank.

It was reported by the company owner that the task of cleaning the freshwater tank had begun at about 8:00 a.m. and that he saw the victim on the pier for break at approximately 11:00 a.m. At this time the victim reported to the company owner that he would be done washing the freshwater tank around noon. The victim returned below deck to complete cleaning the freshwater tank after this break.

The victim usually went home for lunch; when he did not arrive that day, his wife notified co-workers who went to look for him. The victim’s supervisor found the victim unconscious within the freshwater tank, sprawled against the side. The supervisor and another co-worker entered the tank and dragged the victim out of the tank onto the lower deck floor of the vessel, next to where the pressure washer was located. The two co-workers initiated CPR; several other co-workers arrived to assist, while others remained above to seek assistance and a bystander placed calls for help. One of the co-workers turned off the pressure washer.

The initial information provided to the fire and EMS first responders about the location and nature of the illness/injury was not clear, and response was delayed as they looked for the site of the incident. City police and fire arrived first. Two city EMS responders arrived soon after, who descended the ladder to the lower deck and continued CPR on the victim, unaware of the carbon monoxide hazard. The supervisor, who had been administering CPR prior to the arrival of EMS and who remained in the auxiliary engine room next to the victim, then had a seizure. The first responders, realizing a hazard was present, evacuated the victim and his supervisor with the help of the dock co-workers. At this point, the fire department used a multi-gas meter to test the atmosphere, which indicated high CO levels as well as low levels of hydrogen sulfide.

Ten individuals were transported to hospitals, which included the victim, four additional dock workers, four firefighters and one police officer. Two city emergency medical technicians were also subsequently evaluated and another dockworker drove to a hospital later for evaluation. Two of the dockworkers had carboxyhemoglobin levels greater than 20%.* Two dockworkers were admitted to the hospital, and one of these dockworkers received hyperbaric chamber treatment for carbon monoxide poisoning. The victim was pronounced dead at the local hospital where he was transported.

* The normal average range of carboxyhemoglobin is 0-5%, and can be as high as 9% for smokers.

Cause of Death

The medical examiner listed the cause of death as carbon monoxide intoxication.

Recommendations/Discussion

Recommendation #1: Employers should ensure that fuel-burning pressure washers are placed outdoors during operation and that carbon monoxide detectors are placed between the pressure washer and workers.

Discussion: Fuel-burning equipment, such as pressure washers, emits high levels of carbon monoxide (CO) and other hazardous combustion-related particles and gases. Fuel-burning equipment should never be used indoors or in areas of limited ventilation. Locating a fuel-burning pressure washer outdoors, but proximal to an indoor or partially enclosed work location, can also pose a CO hazard, as products of combustion may infiltrate the work area.

During the use of fuel-burning pressure washers, CO detectors should be placed between the pressure washer and the nearest workers or occupants. CO detectors provide a direct reading of ambient CO concentrations, with preset alarm warnings for hazardous concentrations. Personal CO monitors with alarm functions that can be worn by workers are also available. CO detectors use both CO concentration and duration of exposure to trigger the sounding of an audible alarm. Higher concentrations for short durations or lower concentrations for longer durations will both trigger the warning. Any CO alarm should result in the evacuation of the worksite. The fuel-burning equipment should be shut down and its use discontinued until it can be relocated and the work area can be properly ventilated.

If a pressure washer has to be used below deck, then an electric pressure washer with a built in ground fault interrupter (GFCI), should be used. Electric pressure washers can provide comparable cleaning capacity without the combustion hazard. If the electric pressure washer does not have a built in GFCI then it should be plugged into a receptacle or portable GFCI.

Recommendation #2: Employers should develop, implement, and enforce a confined space entry program, as part of a comprehensive health and safety program.

Discussion: Confined and enclosed space operations have a greater likelihood of causing fatalities, severe injuries, and illnesses than any other type of shipyard work.7 A confined space is described as any space with limited access for entry and exit, such as a tank, with limited or no ventilation, which can readily create or aggravate a hazardous exposure. While the space is large enough to allow an employee to enter and perform the assigned work, it is not designed for continuous employee occupancy and has restricted means for entry and exit. Hazardous atmospheres in confined spaces are serious hazards and some examples that may occur within shipyards include ship tanks or holds, pump or engine rooms and crawl spaces. Safety and health requirements regarding confined space and other hazards are described in 29 CFR 1915, OSHA’s Shipyard Employment Standard.8, 9

OSHA specifically requires that employers / shipyards develop and implement confined space programs, including developing a pre-entry program, providing employee training, providing atmospheric testing before entry and periodic retesting, establishing and maintaining communication between workers in the spaces and the assigned worker outside the space, developing rescue procedures, and assigning a competent person. A competent person, as defined by OSHA, is a person who, through training or knowledge, is capable of identifying existing and predictable hazards in the surroundings or working conditions that are unsanitary, hazardous, or dangerous to employees, and who has authorization to take prompt corrective measures to eliminate them.

Tanks are one of the most common locations where confined space fatalities occurr.10 In this case, the employer did not recognize the water tank as a confined space, although it met all of the criteria described. The employer should have tested the atmosphere for CO prior to the victim’s entry and during the task. The employer should also have provided employees with training about confined space hazards and rescue procedures (See Recommendation #3.)

Recommendation #3: Employers of first responders should develop procedures for rescuing victims in enclosed spaces with hazardous atmospheres.

Discussion: According to the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH), confined spaces result in an average of 92 fatalities per year, and 36-60% of confined space fatalities occurred among would-be rescuers.11, 12 As in this case, the incident location was not recognized as a confined space by the employer, therefore this information was not relayed to emergency responders. This resulted in the first responders entering the area unaware of the hazard.

It is important that first responders ensure scene safety for injured people, bystanders, and themselves. One of the most challenging aspects of confined space response for first responders is awareness and recognition of the confined space and all the attendant hazards. The impulse to rescue may contribute to immediate action and placing themselves in danger. In this case, the procedures should include testing the atmosphere prior to entry, and then depending on the results of the testing, developing a plan to evacuate the victim prior to attempting first aid.

In most Massachusetts cities and towns, fire department personnel are the first responders who have access to atmosphere monitoring equipment, self contained breathing apparatuses, and have been provided training to use the equipment. Immediate access to atmosphere monitoring equipment and self contained breathing apparatuses at incident sites will help emergency first responders safely handle situations with potentially hazardous atmospheres.

Recommendation #4: Retailers, distributors and rental agents for fuel burning equipment, such as pressure washers, should affix a carbon monoxide (CO) warning label to equipment and provide customers with a CO fact sheet.

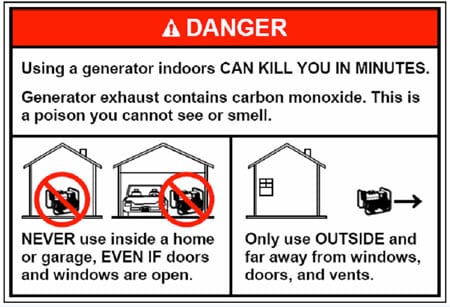

Discussion: Retailers, distributors and rental agents for fuel burning equipment should ensure that all customers who are purchasing or renting fuel-burning equipment understand the hazards of CO by providing them with a CO fact sheet, such as the CO Poisoning FACE Facts developed by Massachusetts FACE or the CO Questions and Answers sheet developed by the Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC).13, 14 In addition, they should also add CO warning label, such as the one developed by the CPSC to all generators, pressure washers and other fuel-burning equipment manufactured (Figure 3).15, 16

Recommendation #5: Manufacturers of fuel-burning pressure washers should affix a warning label about the hazards of carbon monoxide on their equipment.

Discussion: Despite the history of deaths and injuries from fuel-burning equipment, the hazards of CO are still not well recognized. The CPSC issued a final rule in 2007 with a requirement that CO warning labels be displayed on all portable generators and packaging that is manufactured or imported into the United States (16 CFR 1407).16 Manufacturers should take added steps to help educate people about CO by also including CO warnings on other fuel-burning equipment, such as pressure washers. In addition manufacturers should also post instruction manuals that include CO warnings on their web sites.

Recommendation #6: Manufacturers of fuel-burning equipment should develop and promote fuel-burning equipment that emits low levels of carbon monoxide.

Discussion: Some manufacturers have developed generators, primarily used to generate electricity for boats, that emit low levels of CO. These generators use fuel injectors to improve the fuel-to-air ratio and catalytic converters to further reduce CO and hydrocarbons from the exhaust.17, 18 While not broadly commercially available, the technology exists. Manufacturers should develop, promote and make readily available other fuel-burning equipment, such as pressure washers, that emit low levels of CO.

|

|

|

|

Figure 3 – Consumer Product Safety Commission

fuel-burning generator CO warning label. |

References

- National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH), US DHHS, Pubic Health Service, CDC, 1996. NIOSH Alert: Preventing Carbon Monoxide Poisoning from Small Gasoline-Powered Engines and Tools. DHHS (NIOSH) Publication No. 96-118.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Carbon Monoxide Poisonings after Two major Hurricanes – Alabama and Texas, August – October 2005. MMWR Weekly Report March 10, 2006/55(09); 236-239.

- Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC), 16 CFR Part 1407 Portable Generators; Final Rule; Labeling Requirements. Federal Register Vol. 72, No. 8, January 12, 2007. http://www.cpsc.gov/en/Regulations-Laws–Standards/Voluntary-Standards/Topics/Portable-Generators/ (Link updated 4/8/2013 – no longer available 4/9/2015)

- National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH), NIOSH Warns of Deadly Carbon Monoxide Hazard from Using Pressure Washers Indoors. www.cdc.gov/niosh/updates/93-117.html

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Carbon Monoxide Poisoning from Use of Gasoline-Fueled Power Washers in an Underground Parking Garage — District of Columbia, 1994 MMWR Weekly Report May 12, 1995. www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/00037050.htm

- Lofgren DJ, Occupational Carbon Monoxide Poisoning in the State of Washington, 1994–1999. Appl Occup Env Hyg 2002, 17(4):286-295.

- Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), Shipyard Employment eToolexternal icon. www.osha.gov/SLTC/etools/shipyard/shiprepair/confinedspace/index_cs.html

- Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), 29 CFR 1915, Occupational Safety and Health Standards for Shipyard Employmentexternal icon. www.osha.gov/pls/oshaweb/owadisp.show_document?p_table=STANDARDS&p_id=10208

- Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), CPL 02-01-042 – CPL 02-01-042 – 29 CFR Part 1915, Subpart B, Confined and Enclosed Spaces and Other Dangerous Atmospheres in Shipyard Employmentexternal icon. www.osha.gov/pls/oshaweb/owadisp.show_document?p_table=DIRECTIVES&p_id=3308

- National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH), Confined Space Fatalitiespdf icon. Publication number 94-103. www.cdc.gov/niosh/docs/94-103/pdfs/94-103.pdf (Link updated 4/9/2015)

- National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH), NIOSH Safety and Health Topic: Confined Spaces. www.cdc.gov/niosh/topics/confinedspace/

- National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH), Request for Assistant in Preventing Occupational Fatalities in Confined Spaces. Health Alert 86-110. www.cdc.gov/niosh/docs/86-110/

- Massachusetts Department of Public Health (MDPH), Massachusetts FACE Facts: Occupational Poisoningpdf iconexternal icon. www.mass.gov/eohhs/docs/dph/occupational-health/carbon-monoxide.pdf (Link updated 3/21/2013)

- Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC), Carbon Monoxide Questions and Answersexternal icon. Document # 466. http://www.cpsc.gov/en/Safety-Education/Safety-Education-Centers/Carbon-Monoxide-Information-Center/Carbon-Monoxide-Questions-and-Answers-/ (Link updated 4/8/2013)

- Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC), Health Alert, Carbon Monoxide Warning!pdf iconexternal icon http://www.cpsc.gov/PageFiles/112424/05269C.pdf (Link updated 5/28/2013)

- Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC), 16 CFR Part 1407 Portable Generators; Final Rule; Labeling Requirements. Federal Register Vol. 72, No. 8, January 12, 2007. http://www.cpsc.gov/en/Regulations-Laws–Standards/Voluntary-Standards/Topics/Portable-Generators/ (Link updated 4/8/2013 – no longer available 4/9/2015)

- Boat U.S. Magazine, Carbon Monoxide – Converters Cut CO. 2005. www.boatus.com/news/engines_0505.htm

- National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH), An evaluation of catalytic emission controls and vertical exhaust stacks to prevent carbon monoxide poisoning from houseboat generator exhaustpdf icon. www.cdc.gov/niosh/surveyreports/pdfs/171-36a.pdf

To contact Massachusetts State FACE program personnel regarding State-based FACE reports, please use information listed on the Contact Sheet on the NIOSH FACE web site Please contact In-house FACE program personnel regarding In-house FACE reports and to gain assistance when State-FACE program personnel cannot be reached.