Does health insurance impact the survival of babies with heart defects?

A 2014 CDC study published in the American Journal of Public Health looked at the link between health insurance coverage and the survival of a baby born with a heart defect (a congenital heart defect). Researchers found that the type of health insurance coverage was related to the rate of survival among babies born with a heart defect. Health insurance coverage helped explain differences in survival seen between black and white babies born with heart defects. You can read the article’s abstract here.

Main Findings from this Study

- The risk of death was not substantially different between publicly- and privately-insured infants born with a heart defect, except among black infants with a heart defect.

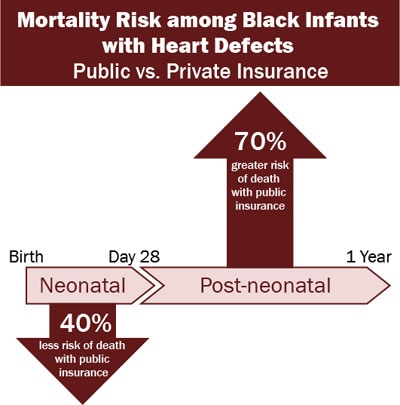

- In the neonatal period, publicly-insured black infants were 40% less likely to die than privately-insured black infants with a heart defect.

In the post-neonatal period, publicly-insured black infants were 70% more likely to die compared to privately-insured black infants with a heart defect. - In the post-neonatal period, babies with heart defects are likely to need follow-up care and continued check-ups with the doctor. Therefore, researchers might be seeing differences in survival during this time period because of factors that affect how well families access healthcare.

- In the neonatal period, publicly-insured black infants were 40% less likely to die than privately-insured black infants with a heart defect.

- Uninsured or underinsured babies born with heart defects were the most vulnerable. This group made up a small number (about 3%) of babies in the study, but infants in this group had a greater risk of death during the first 28 days of life (the neonatal period) compared to infants covered by private insurance.

- Among those with a critical congenital heart defect (severe heart defects that typically require surgery in the first year of life), uninsured babies had three times the risk of death in the first 28 days compared to privately-insured babies.

- Among those with non-critical heart defects, uninsured babies had double the risk of death in the same time period compared to privately-insured babies.

- When researchers took into account the differences in health insurance types [public, private, uninsured/underinsured, or mix (more than 1 type of payer)] between black and white babies, the risk of infant death between black and white babies with heart defects was reduced by 50%, but there was still a difference in survival between black and white infants.

Uninsured or underinsured: These babies either had no insurance (uninsured) or had some health insurance coverage, but not enough to cover all their medical care (underinsured). For this study, both of these types were included in the same category for analysis.

Privately-insured: These babies had health insurance coverage through an employer-based private health insurance company. This health insurance type is usually accessed through a parent’s job.

Publicly-insured: These babies had health insurance coverage through a government program at the federal, state or local level, such as Medicare, Medicaid, or Children’s Health Insurance Program.

About this Study

Researchers used data on babies with congenital heart defects identified by the Florida Birth Defects Registry. These babies were born between 1998 and 2007. Information from hospital stays for these babies during the first year of life was used to examine whether the type of health insurance was related to their survival to one year of age. Researchers also wanted to understand if the type of health insurance coverage was related to the survival of babies with heart defects the same way among different racial and ethnic groups.

More Information

To learn more about congenital heart defects, please visit https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/heartdefects/.

Paper Reference

Kucik JE, Cassell CH, Alverson CJ, Donohue P, Tanner JP, Minkovitz CS, Correia J, Burke T, Kirby RS. Role of health insurance on the survival of infants with congenital heart defects. American Journal of Public Health. 2014

Heart Defects: CDC’s Activities

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) works to identify causes of CHDs and ways to prevent them. We do this through:

- Surveillance and Disease Tracking:

- CDC funds and coordinates the Metropolitan Atlanta Congenital Defects Program (MACDP). CDC also funds population-based state tracking programs. Birth defects tracking systems are vital to help us find out where and when birth defects occur and whom they affect.

- CDC funds projects to track CHDs across the lifespan in order to learn about health issues and needs among all age groups.

- CDC, in partnership with March of Dimes, surveyed adults with CHDs to assess their health, social and educational status, and quality of life. The survey is called CH STRONG, Congenital Heart Survey To Recognize Outcomes, Needs, and well-beinG.

- Research: CDC funds the Centers for Birth Defects Research and Prevention, which collaborate on large studies such as the National Birth Defects Prevention Study (NBDPS) (births 1997-2011) and the Birth Defects Study To Evaluate Pregnancy exposureS (BD-STEPS) (began with births in 2014). These studies are working to identify factors that put babies at risk for birth defects, including heart defects.

- Collaboration:

- CDC is assessing states’ needs for help with CCHD screening and reporting of screening results. CDC helps states and hospitals better understand the cost and impact of CCHD screening. CDC also promotes collaboration between birth defects tracking programs and newborn screening programs to improve understanding of the effectiveness of CCHD screening.

- CDC provides technical assistance to the Congenital Heart Public Health Consortium (CHPHC). The CHPHC is a group of organizations uniting resources and efforts in public health activities to prevent congenital heart defects and improve outcomes for affected children and adults. Their website provides resources for families and providers on CHDs.