|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

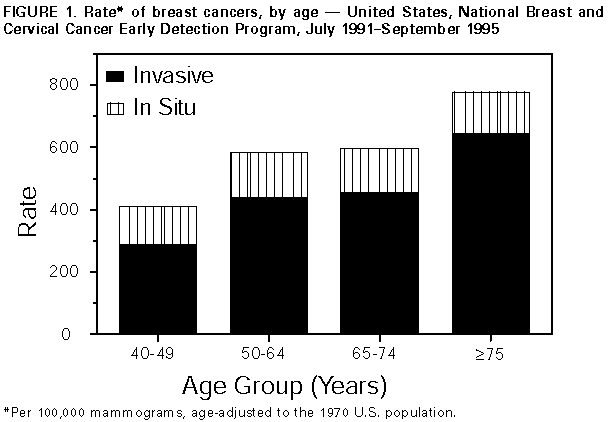

Persons using assistive technology might not be able to fully access information in this file. For assistance, please send e-mail to: mmwrq@cdc.gov. Type 508 Accommodation and the title of the report in the subject line of e-mail. Update: National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program -- July 1991-September 1995During the 1990s, breast or cervical cancer will be diagnosed in an estimated 2 million women in the United States, and 500,000 will die as a result of these diseases (1). Screening mammography followed by timely and appropriate treatment can reduce breast cancer mortality by 30% for women aged 50-69 years, and routine use of the Papanicolaou (Pap) test followed by timely and appropriate treatment can prevent nearly all deaths from cervical cancer (2,3). The Breast and Cervical Cancer Mortality Prevention Act of 1990 * established a nationwide, comprehensive public health program for increasing access to breast and cervical cancer screening services for underserved women. This report summarizes the impact of this initiative, CDC's National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program (NBCCEDP), during July 1991-September 1995. During the reporting period, the NBCCEDP was implemented in 35 state health agencies and nine American Indian/Alaskan Native programs that provided screening, referral, and follow-up services; public and professional education; quality assurance; surveillance; and coalition and partnership development. Outreach efforts were initiated to women in high-priority groups, including older women, women with low income, uninsured or underinsured women, or women of approximately 800,000 screenings for breast and cervical cancer were provided to uninsured or underinsured women. During July 1991-September 1995, the program provided 327,017 mammograms; 61.2% of the mammograms were provided to women aged greater than or equal to 50 years, and 46.7% were provided to women of racial and ethnic minorities. Breast cancer was diagnosed in 1674 of the women who received mammograms. Although the rate of abnormalities detected by mammogram was highest for younger women, the rate of breast cancers detected per 100,000 mammograms increased directly with increasing age (Figure_1). A total of 472,188 Pap tests were performed; 59.1% of the Pap tests were provided to women aged greater than or equal to 40 years, and 46.5% were provided to women in racial/ethnic minorities. Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia, a precursor of cervical cancer that can be successfully treated, was diagnosed in 15,119 women. Invasive cervical cancer was diagnosed in 184 women. The rate of abnormal Pap tests varied inversely with age. Reported by: Program Svcs Br and Office of the Director, Div of Cancer Prevention and Control, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, CDC. Editorial NoteEditorial Note: The national health objectives for the year 2000 include increasing to at least 60% the proportion of women in low-income groups and aged greater than or equal to 50 years who have received a clinical breast examination and mammogram within the preceding 2 years and increasing to at least 80% the proportion of low-income women and women aged greater than or equal to 18 years (with uterine cervix) who have received a Pap test within the preceding 3 years (objectives 16.11b and 16.12d) (4). The Breast and Cervical Cancer Mortality Prevention Act has enabled state health agencies to build a public health infrastructure to increase access to breast and cervical cancer screening services for women who are medically underserved. During fiscal year 1996, CDC entered the sixth year of the program; the number of women screened for breast and cervical cancer has increased substantially each year. Although screening mammography and Pap tests are essential strategies for cancer prevention and control, these procedures have been substantially underused. The most important risk factors for breast cancer are female sex and older age (5); however, findings from the 1992 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) indicated that only 35% of women aged greater than or equal to 50 years reported having had a screening mammogram during the previous year. In addition, even though cervical cancer death rates are higher among older women (6), older women are less likely to receive Pap tests on a regular basis (3). The 1992 NHIS indicated that only 63% of women aged 50-64 years reported having had a Pap test during the previous 3 years (7). Use of mammograms and Pap tests was lower among women of racial/ethnic minorities, women who had less than a high school education, and women who had a low income (7). Reasons for the low proportion of women who use these screening tests include lack of a recommendation for screening from a health-care provider, costs associated with the tests, and lack of an understanding of the value of early detection. Early detection programs at the state and community levels control, innovative public and professional education programs for women and health-care providers, collaborative partnerships involving the private and public sectors, state and community coalitions, and improved understanding of the barriers that prevent underserved women from seeking screening services. Improvements in measures for ensuring quality of screening tests and the establishment of public and private partnerships have benefitted all women. For example, when the NBCCEDP was implemented in 1991, provider agencies participating in the program were required to meet technical guidelines for mammography and cytology services, which included having all mammography facilities meet standards established by the American College of Radiology and the Food and Drug Administration and all cytology laboratories meet standards established by the Clinical Laboratory Improvements Act of 1988. To promote the importance of screening services for all women, CDC has developed partnerships with national organizations such as the American Cancer Society, Young Women's Christian Association of the USA, and Susan G. Komen Breast Cancer Foundation. During fiscal year 1996, CDC received Congressional appropriations of $125 million for breast and cervical cancer control. CDC now provides funding to 35 states and nine American Indian/Alaskan Native programs for comprehensive screening programs, and infrastructure grants have been provided to 15 states, the District of Columbia, and three territories. During 1996, CDC will implement a nationwide comprehensive screening program by funding the remaining 15 states, the District of Columbia, and several of the U.S. territories. References

Figure_1  Return to top. Disclaimer All MMWR HTML versions of articles are electronic conversions from ASCII text into HTML. This conversion may have resulted in character translation or format errors in the HTML version. Users should not rely on this HTML document, but are referred to the electronic PDF version and/or the original MMWR paper copy for the official text, figures, and tables. An original paper copy of this issue can be obtained from the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office (GPO), Washington, DC 20402-9371; telephone: (202) 512-1800. Contact GPO for current prices. **Questions or messages regarding errors in formatting should be addressed to mmwrq@cdc.gov.Page converted: 09/19/98 |

|||||||||

This page last reviewed 5/2/01

|