|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

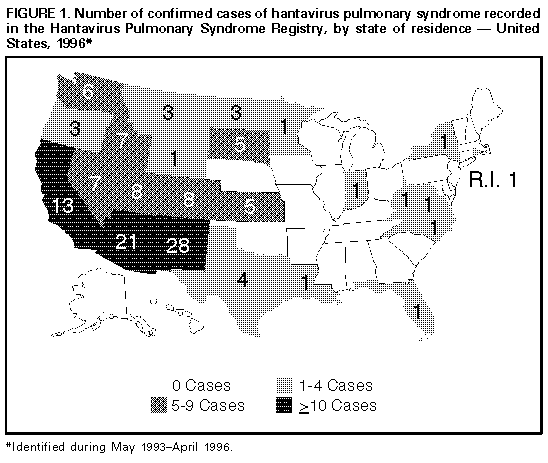

Persons using assistive technology might not be able to fully access information in this file. For assistance, please send e-mail to: mmwrq@cdc.gov. Type 508 Accommodation and the title of the report in the subject line of e-mail. Hantavirus Pulmonary Syndrome -- United States, 1995 and 1996Sporadic cases of hantavirus pulmonary syndrome (HPS), a severe cardiopulmonary illness first identified in 1993, continue to be recognized in the United States (1,2). This report describes the investigation of two cases of Sin Nombre virus (SNV)-associated HPS involving feedlot workers in a single household during May-June 1995, and summarizes national reporting for HPS through March 21, 1996. The findings of this investigation and of other investigations suggest that, although domestic and occupational exposures to rodents have rarely resulted in infection, sporadic clusters of HPS probably will continue to occur even though individual cases will predominate. Patient 1 On May 29, a 27-year-old South Dakota resident sought care at an emergency department because of a 2-day history of fever, chills, headache, myalgia, nausea, vomiting, and nonproductive cough. His temperature was 103 F (39 C) and pulse rate, 118/min. A complete blood count (CBC) included decreased platelets (117,000/mm superscript 3 {normal: 130,000-400,000/mm superscript 3}) and a white blood cell count (WBC) of 6560/mm superscript 3 (normal: 4500-11,000/mm superscript 3); chest radiographs were normal. An acute febrile illness was diagnosed, and he was discharged to outpatient follow-up. On June 1, he was admitted to the hospital because of persistent fever (101 F-104 F {38 C-40 C}), tachycardia (pulse rate 140/min), and hypotension (blood pressure 70/50 mm Hg). In addition to thrombocytopenia (platelet count 35,000/mm superscript 3) and a mildly elevated WBC (11,470/mm superscript 3 {18% segmented neutrophils, 54% banded neutrophils, 19% lymphocytes, 2% immature granulocytes}), other abnormal laboratory findings included mild azotemia (blood urea nitrogen 38 mg/dL {normal: 9-21 mg/dL} and creatinine 2.0 mg/dL {normal: 0.8-1.5 mg/dL}), hypoalbuminemia (3.3 g/dL {normal: 3.5-5.0 g/dL}), and elevated serum enzyme levels (lactic dehydrogenase {LDH} 2473 U/L {normal: 297-628 U/L}; aspartate aminotransferase {AST} 226 U/L {normal: 14-50 U/L}; and alanine aminotransferase {ALT} 138 U/L {normal: 7-56 U/L}). Although he reported no abdominal pain and the abdominal examination on admission was normal, serum amylase and lipase levels were elevated (amylase 226 U/L {normal: 30-110 U/L} and lipase 771 U/L {normal: 23-300 U/L}). Chest radiographs at the time of admission demonstrated perihilar interstitial infiltrates. During June 1-4, he became progressively hypoxemic and developed pulmonary alveolar edema and oliguria. His status improved with supportive therapy, and he was discharged June 6 with a diagnosis of possible pancreatitis and/or hepatitis. Patient 2 On June 27, the 24-year-old coworker and roommate of patient 1 sought care at an emergency clinic because of a 1-day history of fever, chills, headache, myalgia, sweating, and nonproductive cough. Physical examination, chest radiographs, serum chemistries, and CBC were normal. On June 28, because of worsening symptoms, he was admitted to a local hospital for observation and symptom-based therapy. On June 30, he was transferred to a regional hospital because of tachypnea (respiration rate 34-38/min), progressive thrombocytopenia (platelet count from 142,000/mm superscript 3 to 24,000/mm superscript 3), and a left shift in WBC (from 6% to 24% banded forms). He also had developed transient oliguria (no azotemia) during treatment with supplemental fluid therapy. Other laboratory abnormalities included hypoalbuminemia (2.0 g/dL), elevated serum enzymes (LDH 1541 U/L; AST 79 U/L; and creatine phosphokinase 719 U/L {normal: 55-170 U/L}), and hypoxia (80% O subscript 2 saturation with no supplemental O subscript 2). Initial chest radiographs demonstrated segmental alveolar consolidation; subsequent radiographs indicated generalized pulmonary edema. During July 1-4, he responded to continued supportive care and was discharged on July 5 with a diagnosis of suspected HPS. Follow-Up Investigation Acute- and convalescent-phase serum specimens from patient 2 were submitted to the South Dakota Public Health Laboratory and CDC for hantavirus diagnostic testing. Analysis using an enzyme-linked immunoglobulin capture immunosorbent assay detected immunoglobulin M (IgM) and immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibodies to SNV that indicated acute infection. After the diagnosis of SNV was confirmed in patient 2, serum specimens were obtained from patient 1 for testing and were positive for SNV IgM and IgG antibodies. Both ill persons resided in the same house, which was on the premises of a small cattle feedlot at which they were employed. There were no other members of the household, and the only other person who worked at the feedlot had no history of past or recent illness. Investigation at the feedlot identified multiple potential exposures to rodents or rodent-infested environments (typical in such settings), including straw and hay piles stored in fields, abandoned farm buildings, open-access feed storage sites, and buildings with excess accumulations of dirt, debris, and spilled feed. The feedlot did not maintain a coordinated rodent-control program. In addition, the investigation identified opportunities for contact with potentially infected rodents or their excreta, including handling of dead rodents; feeding of the rodent carcasses to cats and dogs; and cleaning of food storage areas, animal- handling facilities, outbuildings, and living quarters in which evidence of rodent harborage was present. To characterize the local reservoir for SNV, rodent trapping surveys are planned for spring 1996. Reported by: WW Hoffman, MD, RG Henrickson, MD, WJ Wengs, MD, JW Crump, MD, M Keppen, MD, Central Plains Clinic, PL Carpenter, MD, North Central Heart, Sioux Falls; D Webb, Deuel County Memorial Hospital, Clear Lake; S Reiffenberger, MD, Brown Clinic, Watertown; B Bleeker, JR Ostby, MD, CA Roseth, MD, Bartron Clinic, Watertown; EG Nelson, MD, M Vossler, MD, Prairie Lakes Hospital, Watertown; S Lance, DVM, State Epidemiologist; L Volmer, L Schaefer, South Dakota Dept of Health; R Steece, PhD, South Dakota Public Health Laboratory. Special Pathogens Br, Div of Viral and Rickettsial Diseases, National Center for Infectious Diseases, CDC. Editorial NoteEditorial Note: HPS was first recognized in 1993 following the investigation of an outbreak of fatal acute respiratory illness in the southwestern United States (3). Since its initial identification, 131 cases have been confirmed in the United States through March 21, 1996. HPS cases have been recognized in 24 states; the largest numbers have occurred in New Mexico (28 cases), Arizona (21 cases), and California (13 cases) (Figure_1). Cases of HPS also have been confirmed in Argentina, Brazil, and Canada. The mean age of the 131 U.S. patients with HPS was 35 years range: 11-69 years), and the overall case-fatality rate was 49.6%. Most HPS cases in the United States are caused by SNV infection. The principal host for SNV is the deer mouse (Peromyscus maniculatus), which is widely distributed in North America (4). Other cases of HPS outside the ecologic range of P. maniculatus have been described and associated with other rodent reservoirs, including the cotton rat (Sigmodon hispidus) -- associated with Black Creek Canal virus identified in south Florida (1); the rice rat (Orysomys palustris) -- associated with Bayou virus in Louisiana (2); and the white-footed mouse (P. leucopus) -- associated with a closely related variant of SNV in New York (5). This report describes the fourth reported instance of multiple cases of SNV-associated illness (3,6; CDC, unpublished data, 1994). In the investigation described in this report, it was not possible to distinguish whether the infections were acquired occupationally or within the home because the persons lived and worked in the same location. The low frequency of case clustering with SNV also is characteristic of the other principal form of hantaviral disease, hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome, which occurs primarily in Europe and Asia (7). Cases of potential occupationally related SNV infection have been recognized but are infrequent (8,9). Among the 131 documented HPS cases in the United States, the exposures related to these cases occurred among grain farmers; an extension livestock specialist; field biologists; and agricultural, mill, construction, utility, and feedlot workers. In addition, in a 1994 study, antibody to SNV was detected in six of 528 mammalogists and rodent workers with varying degrees of rodent exposure in the United States (9). In contrast, no serologic evidence of infection was detected during a seroprevalence study of selected occupational groups (e.g., farm workers, laborers, professionals, repairers, service industry workers, and technicians) * for which the primary jobs did not require rodent contact but whose work activities included potential contact with rodents and rodent excreta in the southwestern United States (8). Recommendations to reduce the risk for exposure to hantavirus include precautions for persons involved in activities associated with exposure to rodents, rodent excreta, and contaminated dust (10). Through the HPS registry, CDC in collaboration with other state health departments is reviewing the utility and impact of these risk-reduction measures during such activities and in related vocations. Collaborative reporting by health-care providers and state health departments to the centralized surveillance system at CDC continues to be essential for characterizing the clinical spectrum of disease, refining the diagnostic criteria for HPS, identifying additional pathogenic hantaviruses and rodent hosts, and identifying additional risk factors for hantavirus infection. References

Coded by CDC's National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. Figure_1  Return to top. Disclaimer All MMWR HTML versions of articles are electronic conversions from ASCII text into HTML. This conversion may have resulted in character translation or format errors in the HTML version. Users should not rely on this HTML document, but are referred to the electronic PDF version and/or the original MMWR paper copy for the official text, figures, and tables. An original paper copy of this issue can be obtained from the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office (GPO), Washington, DC 20402-9371; telephone: (202) 512-1800. Contact GPO for current prices. **Questions or messages regarding errors in formatting should be addressed to mmwrq@cdc.gov.Page converted: 09/19/98 |

|||||||||

This page last reviewed 5/2/01

|