|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

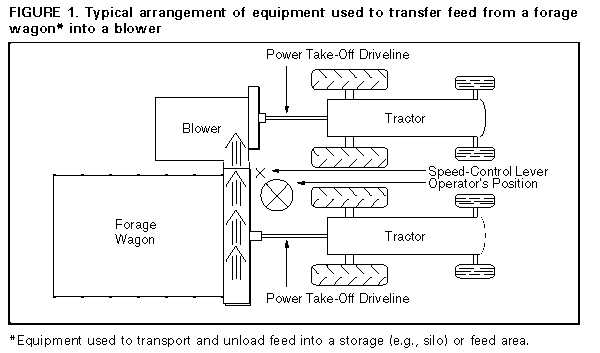

Persons using assistive technology might not be able to fully access information in this file. For assistance, please send e-mail to: mmwrq@cdc.gov. Type 508 Accommodation and the title of the report in the subject line of e-mail. Injuries Associated with Self-Unloading Forage Wagons -- New York, 1991-1994In New York, an estimated 3600 injuries occur each year to farmers operating farm machines (1). In October 1993, the Occupational Health Nurses in Agricultural Communities (OHNAC) * program in the New York State Department of Health received a report of a man who sustained severe injuries when he became entangled in the power take-off (PTO) driveline to a self-unloading forage wagon **. Subsequent investigation by OHNAC identified four additional similar incidents in New York that occurred during September 1991-October 1994, including one fatality and one injury to a 9-year-old girl working on a family farm. This report summarizes the results of the investigation of these forage-wagon-related injuri for such injuries. On October 1, 1993, a 66-year-old farmer was using a self-unloading forage wagon to unload chopped corn into a blower for transfer into a silo. To unload the corn, he used a tractor to pull the loaded forage wagon next to the blower (which was attached to a second tractor). To reach the speed-control lever, he stepped over the rotating PTO driveline that connected his tractor to the wagon and supplied its power. As he stepped, his pants became entangled around the unprotected rotating driveline. A nearby worker witnessed the incident and turned off the driveline. The farmer's injuries included amputation of the genitalia and deep tissue damage to the buttocks, requiring extensive grafting. He was hospitalized for 2 weeks and unable to work for 1 month. On investigation by OHNAC, with assistance from the Cooperative Extension Service, four other incidents were identified since 1991 involving forage wagons with unprotected drivelines. In September 1991, a 33-year-old farmer sustained multiple fractures of the right leg with amputation of the right foot when his shirt blew into a rotating driveline of a forage wagon while he was working between two drivelines on a windy day. In October 1992, a 41-year-old farm operator sustained avulsion of the entire scrotal area when his pants became entangled while he was stepping over the unprotected PTO driveline. In November 1992, a 9-year-old girl sustained bilateral above-the-knee amputations when her jacket became entangled while she was reaching over the unprotected rotating driveline to operate the speed control of the forage wagon she was unloading. Finally, in an unwitnessed incident in October 1994, a 19-year-old male farmer sustained fatal internal injuries after apparently stepping too close to the driveline of a forage wagon while unloading chopped corn. Reported by: S Roerig, J Melius, MD, J Pollock, MSP, M London, MS, G Casey, New York State Dept of Health. Div of Surveillance, Hazard Evaluations, and Field Studies, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, CDC. Editorial NoteEditorial Note: In the United States, farm machinery is a leading source of traumatic injuries to farmers, accounting for an estimated 34,000 lost-time work injuries to farmers nationally in 1993 (2). Mechanical devices are associated with approximately 30% of the work-related injuries on farms (2). Forage wagons are used most often on farms that raise large animals and grow their own feed grain. The fatal and severe nonfatal injuries described in this report were caused by a combination of factors. To unload feed grain, the forage wagon and silo blower must be in close proximity, which requires that the two tractors that power these machines also be in close proximity Figure_1. The speed-control lever for the wagon is often located on the discharge side near the silo blower (i.e., between the two pieces of equipment). Many older tractors are small enough that, when the forage wagon and blower are thus positioned for proper operation, sufficient space remains between the adjacent rear tires of the two tractors to allow the operator to dismount from either tractor seat and walk between the two tractors directly to the forage wagon speed control without crossing over a revolving PTO driveline. However, as both silos and self-unloading forage wagons have increased in capacity, both the size and horsepower of the associated tractors have increased concomitantly. When these larger tractors are used, their rear wheels abut, blocking access between the tractors and requiring the operator to cross over a revolving driveline to operate the forage wagon. Since the 1930s, PTO drivelines have been manufactured with shields. However, shields are often damaged or removed during operation or maintenance of the farm equipment. Of the estimated 29,000 self-unloading wagons in use on New York farms, 3000-5000 are believed to lack shields to protect workers adequately from a revolving PTO driveline (J. Pollock, Cornell University, personal communication, 1995). Entanglement in PTO drivelines, including entanglement in those equipped with intact U-shaped shields that leave one side (generally the underside) unguarded, previously has been recognized as a hazard in the agricultural industry (3-6). Drivelines should be equipped with proper functioning guards in any work situation, *** especially when the worker must work between two operating PTO drivelines. Furthermore, workers must be trained in safe work practices, which include shutting off PTO drivelines whenever possible before dismounting tractors, maintaining warning decals, not wearing loose or bulky clothing around and avoiding close proximity to rotating PTO drivelines, and keeping bystanders -- especially children -- away from PTO-driven equipment (7). To assist in preventing injuries to children, farmers should recognize that farm equipment is designed for operation by adults; be aware of the physical, emotional, and mental characteristics and abilities of children; and select age-appropriate tasks for children (8). Because of the need for immediate response to serious injuries, workers should not work alone when using hazardous equipment; however, if persons do work alone, they should be monitored frequently to ensure immediate response in the event of injuries (7). The National Institute for Farm Safety is reviewing approaches to reduce the risk for forage-wagon-related injuries. In addition to proper shielding of the drivelines, placement of the speed-control devices to enable operation of such devices from the tractor driver's seat or from another location on the wagon would eliminate the need for the operator to step over the driveline. Leading manufacturers of forage wagons have designed conveyor extensions that allow for an increase in the space between the two tractors; the extension can be supplied with new equipment or used to retrofit some older equipment. An informal survey of forage wagon equipment indicated that conveyor extensions are available for all seven wagons selected in a nonrandom sample; costs for the retrofits ranged from $35 to $600 each. Although these extensions are marketed to promote productivity, not safety, manufacturers and dealers should be made aware that these extensions can contribute to safer operation of the equipment, and farmers should be encouraged to use them to enhance safety as well as increase productivity. In New York, OHNAC, in collaboration with farm groups, have alerted farmers about the hazards associated with PTO drivelines -- especially on forage wagons -- through educational presentations and articles in regional agricultural publications. References

* OHNAC is a national surveillance program conducted by CDC's National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health that has placed public health nurses in rural communities and hospitals in 10 states (California, Georgia, Iowa, Kentucky, Maine, Minnesota, New York, North Carolina, North Dakota, and Ohio) to conduct surveillance for agriculture-related illnesses and injuries that occur among farmers and their family members. These surveillance data are used to assist in reducing the risk for occupational illness and injury in agricultural populations. ** A forage wagon is used to transport and unload feed into a storage (e.g., silo) or feed area. *** 29 CFR section 1928.57. Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) Standard for Safety for Agricultural Equipment. Family-run farms with no other employees are exempt from compliance with federal OSHA standards, and those with less than or equal to 10 employees are generally not subject to OSHA inspection. Figure_1  Return to top. Disclaimer All MMWR HTML versions of articles are electronic conversions from ASCII text into HTML. This conversion may have resulted in character translation or format errors in the HTML version. Users should not rely on this HTML document, but are referred to the electronic PDF version and/or the original MMWR paper copy for the official text, figures, and tables. An original paper copy of this issue can be obtained from the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office (GPO), Washington, DC 20402-9371; telephone: (202) 512-1800. Contact GPO for current prices. **Questions or messages regarding errors in formatting should be addressed to mmwrq@cdc.gov.Page converted: 09/19/98 |

|||||||||

This page last reviewed 5/2/01

|