Strategies for Addressing Asthma within a Coordinated School Health Program

A healthy student is a student ready to learn. Asthma-friendly schools are those that make the effort to create safe and supportive learning environments for students with asthma. They have policies and procedures that allow students to successfully manage their asthma. Chances for success are better when the whole school community takes part–school administrators, teachers, and staff, as well as students and parents.

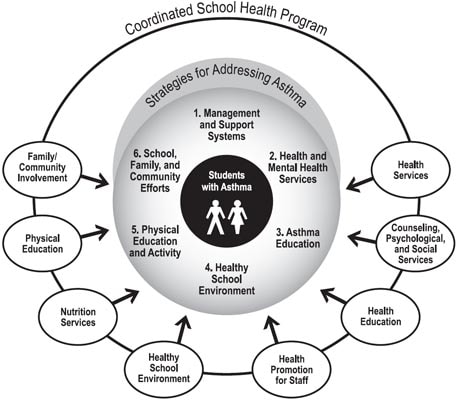

CDC has identified six strategies for schools and districts to consider when addressing asthma within a coordinated school health program. These strategies can be effective whether your program is for the entire school district or just one school.

- Establish management and support systems for asthma-friendly schools.

- Provide appropriate school health and mental health services for students with asthma.

- Provide asthma education and awareness programs for students and school staff.

- Provide a safe and healthy school environment to reduce asthma triggers.

- Provide safe, enjoyable physical education and activity opportunities for students with asthma.

- Coordinate school, family, and community efforts to better manage asthma symptoms and reduce school absences among students with asthma.

These strategies are based on six key elements of school-based education and intervention developed by expert panelists at the November 2000 national conference, “Asthma Prevention, Management, and Treatment: Community-Based Approaches for the New Millennium,” sponsored by Kaiser Permanente and the American Lung Association.1 Two National Asthma Education and Prevention Program (NAEPP) documents, Resolution on Asthma Management at School2 and How Asthma-Friendly is Your School?3 were used to develop these school-focused elements. CDC’s school asthma strategies also incorporate the eight interactive components of the coordinated school health program, a model used by the CDC and many state education agencies and school districts.4 These six strategies for addressing asthma fit within the eight components of a coordinated school health program, and are illustrated below.

Addressing Asthma within a Coordinated School Health Program

Implementation of the strategies will require a team effort that involves all school administrators, faculty, and staff, as well as students and parents. These strategies can be used to develop a plan for addressing asthma within a coordinated school health program. They complement NAEPP’s Managing Asthma: A Guide for Schools,5 which provides specific action steps for school staff members.

Every strategy is not appropriate or feasible for every school to implement. Schools and districts should determine which strategies have the highest priority on the basis of the needs of the school and available resources. Schools and districts should, whenever possible, initially focus their asthma programs on students with poorly managed, moderate-to-severe persistent asthma as demonstrated by frequent school absences, school health office visits, emergency department visits, or hospitalizations. Low-income, minority populations and inner-city residents experience more emergency department visits, hospitalizations, and deaths due to asthma than the general population.6,7

1. Establish management and support systems for asthma-friendly schools.

- Identify your school’s or district’s existing asthma needs, resources for meeting those needs, and potential barriers.

- Designate a person to coordinate asthma activities at the district and school levels. If your school or district has a health coordinator, determine if asthma coordination can be integrated into his or her activities.

- Share these strategies with the district health council and school health team if they exist. If you do not have a council or team, help create them. Ensure that school-based asthma management is addressed as a high priority.8

- Develop and implement written policies and procedures regarding asthma education and management. Promote asthma programs that are culturally and linguistically appropriate.9,10

- Use or adapt existing school health records to identify all students with diagnosed asthma.

- Use health room and attendance records to track students with asthma. Focus particularly on students with poorly managed asthma as demonstrated by frequent school absences, school health office visits, emergency room visits, or hospitalizations. Avoid mass screening* and mass case detection† as methods for routine identification. These methods have not been shown to meet the World Health Organization’s or American Academy of Pediatrics’s criteria for population or school screening programs.11-16

- Use 504 Plans or Individualized Education Plans (IEPs), as appropriate, especially for health services and physical activity modifications.

- Obtain administrative support and seek support from others in the school and community for addressing asthma within a coordinated school health program.

- Develop systems to promote ongoing communication among students, parents, teachers, school nurses, and health care providers to ensure that students’ asthma is well-managed at school.

- Seek available federal, state, and private funding for school asthma programs.

- Evaluate asthma program strategies and policies annually. Use this information to improve programs.

*Screening for asthma (spirometry) can identify students who, in a test situation, exhibit signs and symptoms of asthma. These students may or may not truly have asthma.

†Case detection (symptom questionnaires) can identify students with asthma symptoms who may or may not have the disease. Only testing and evaluation by a health professional can confirm which students truly have asthma.

2. Provide appropriate school health and mental health services for students with asthma.

- Obtain a written asthma action plan for all students with asthma. The plan should be developed by a primary care provider and be provided by parents. It should include individualized emergency protocol, medications, peak flow monitoring, environmental triggers, and emergency contact information.17–19 Share the plan with appropriate faculty and staff in accordance with the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA) guidelines or with parental permission.20

- Ensure that at all times students have immediate access to medications, as prescribed by a physician and approved by parents. Specific options, such as allowing students to self-carry and self-administer medications, should be determined on a case-by-case basis with input from the physician, parent, and school.21

- Use standard emergency protocols for students in respiratory distress if they do not have their own asthma action plan.1

- Ensure that case management‡ is provided for students with frequent school absences, school health office visits, emergency department visits, or hospitalizations due to asthma.22

- Provide a full-time registered nurse all day, every day for each school.1

- Ensure access to a consulting physician for each school.1

- Refer students without a primary care provider to child health insurance programs and providers.23,24

- Provide and coordinate school-based counseling, psychological, and social services for students with asthma, as appropriate. Coordinate with community services.18,22,25

‡ Case management by a trained professional includes assessing needs and planning a continuum of care for students and families.

3. Provide asthma education and awareness programs for students and school staff.

- Ensure that students with asthma receive education on asthma basics, asthma management, and emergency response. Encourage parents to participate in these programs.19,26–30

- Provide school staff with education on asthma basics, asthma management, and emergency response as part of their professional development activities. Include classroom teachers, physical education teachers, coaches, secretaries, administrative assistants, principals, facility and maintenance staff, food service staff, and bus drivers.31–35

- Integrate asthma awareness and lung health education lessons into health education curricula.36

- Provide and/or support smoking prevention and cessation programs for students and staff.37

4. Provide a safe and healthy school environment to reduce asthma triggers.

- Prohibit tobacco use at all times, on all school property (including all buildings, facilities, and school grounds), in any form of school transportation, and at school-sponsored events on and off school property (for example, field trips).37–41

- Prevent indoor air quality problems by reducing or eliminating allergens and irritants, including tobacco smoke; dust and debris from construction and remodeling; dust mites, molds, warm-blooded animals, cockroaches, and other pests.42–45

- Use integrated pest management (IPM)§ techniques to control pests.46,47

§ IPM is a proactive approach to pest management that includes looking for signs of pests, controlling water and food sources, removing pest pathways and shelters, and safely using pest control products as needed.

5. Provide safe, enjoyable physical education and activity opportunities for students with asthma.

- Encourage full participation in physical activities when students are well.48,49

- Provide modified activities as indicated by a student’s asthma action plan, 504 Plan, and/or IEP, as appropriate.1

- Ensure that students have access to preventive medications before activity and immediate access to emergency medications during activity.50–52

6. Coordinate school, family, and community efforts to better manage asthma symptoms and reduce school absences among students with asthma.

- Obtain written parental permission for school health staff and primary care providers to share student health information.53

- Educate, support, and involve family members in efforts to reduce students’ asthma symptoms and school absences.33,54

- Work with local community programs. Coordinate school and community services, including community health care providers, community asthma programs and coalitions, community counselors, social workers, case managers, and before- and after-school programs. Encourage interested school staff to participate in community asthma coalitions.

- Kaiser Permanente/American Lung Association National Partnership on Asthma. National asthma conference: asthma prevention, management, and treatment: community-based approaches for the new millennium. Washington, DC: Kaiser Permanente, American Lung Association, November 2000.

- National Asthma Education and Prevention Program. Resolution on asthma management at school. Bethesda, Maryland: National Asthma Education and Prevention Program, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, 1997.

- National Asthma Education and Prevention Program. How asthma-friendly is your school? Bethesda, Maryland: National Asthma Education and Prevention Program, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, 1997.

- Allensworth DD, Kolbe LJ. The comprehensive school health program: exploring an expanded concept. J Sch Health 1987;57(10): 409–12.

- National Asthma Education and Prevention Program. Managing asthma: a guide for schools. Bethesda, Maryland: National Asthma Education and Prevention Program, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, 2002.

- Public Health Service. Action against asthma: a strategic plan for the Department of Health and Human Services. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, May 2000.

- Lieu TA, Lozano P, Finkelstein JA, Chi FW, Jensvold NG, Capra AM. Racial/ethnic variation in asthma status and management practices among children in managed Medicaid. Pediatrics 2002;109:857–65.

- Coover L, Vega C, Persky V, Russell E, Blasé R, Wolf R. Collaborative model to enhance the functioning of the school child with asthma. Chest 1999;116(suppl 4):193S–5S.

- American Association for Health Education. Cultural awareness and sensitivity: guidelines for health educators. Reston, Virginia: American Association for Health Education, 1994.

- American Association for Health Education. Cultural awareness and sensitivity: resources for health educators. Reston, Virginia: American Association for Health Education, 1994.

- Gerald LB, Redden D, Turner-Henson A, Feinstein R, Hemstreet MP, Hains C. A multi-stage asthma screening procedure for elementary school children. J Asthma 2002;39(1):29–36.

- Wilson JMG, Junger F. Principles and practice of screening for disease. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 1968. Public health papers no. 34.

- American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on School Health. School health policy and practice: criteria for successful screening. Elk Grove Village, Illinois: American Academy of Pediatrics, 1993;89.

- Yawn BP, Wollan P, Scanlon P, Kurland M. Are we ready for universal school-based asthma screening?: An outcomes evaluation. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2002;156(12):1256–62.

- Yawn BP, Wollan P, Scanlon PD, Kurland M. Outcome results of a school-based screening program for undertreated asthma. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2003;90(5):508–15.

- Boss LP, Wheeler LS, Williams PV, Bartholomew LK, Taggart VS, Redd SC. Population-based screening or case detection for asthma: Are we ready? J Asthma 2003;40(4):335–42.

- Abramson MJ, Bailey MJ, Couper FJ, Drummer OH, Forbes AB, McNeil JJ. Are asthma medications and management related to deaths from asthma? Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2001;163:12–8.

- Lwebuga-Mukasa J, Dunn-Georgiou E. A school-based asthma intervention program in the Buffalo, New York schools. J Sch Health 2002;72(1):27–32.

- National Institutes of Health. Clinical practice guidelines: expert panel report 2: guidelines for the diagnosis and management of asthma. Rockville, Maryland: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, 2002. NIH publication 97-4051.

- U.S. Department of Education. Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA) regulations. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education, 2002.*

- Madden JA. Managing asthma at school. Educ Leader March 2000;57(6):50–2.

- Evans R, Gergen PJ, Mitchell H, Kattan M, Kercsmar C, Crain E. A randomized clinical trial to reduce asthma morbidity among inner-city children: results of the National Cooperative Inner-city Asthma Study. J Pediatr 1999;135(3):332–8.

- Raskin L. Breathing easy: solutions in pediatric asthma. Washington, DC: National Center for Education in Maternal and Child Health, Georgetown University, February 2000.*

- Lara M, Nicholas W, Morton SC, Vaiana M, Genovese B, Rachelefsky G. Improving childhood asthma outcomes in the United States: a blueprint for policy action. Pediatrics 2002;109(5):919–30.

- Fritz GK, McQuaid EL, Spirito A, Klein RB. Symptom perception in pediatric asthma: relationship to functional morbidity and psychological factors. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1996;35(8):1033–41.

- Clark NM, Partridge MR. Strengthening asthma education to enhance disease control. Chest 2002;121(5):1661–9.

- Evans D, Clark M, Feldman C, Rips J, Kaplan D, Levison M. A school health education program for children with asthma aged 8–11 years. Health Educ Q 1987; 14:267–79.

- Evans D, Clark N, Levison M, Levin B, Mellins R. Can children teach their parents about asthma? Health Educ Behav 2001; 28:500–11.

- Spencer G, Atav S, Johnston Y, Harrigan J. Managing childhood asthma: the effectiveness of the Open Airways for Schools program. Fam Community Health 2000;23:20–30.

- Gregory EK. Empowering students on medication for asthma to be active participants in their care: an exploratory study. J Sch Nursing 2000; 16(1):20–7.

- Fillmore EJ, Jones N, Blankson JM. Achieving treatment goals for schoolchildren with asthma. Arch Dis Child 1997;77:420–2.

- Atchison JM, Cuskelly M. Educating teachers about asthma. J Asthma 1994;31(4):269–76.

- Henry RL, Hazell J, Halliday JA. Two hour seminar improves knowledge about childhood asthma in school staff. J Paediatr Child Health 1994;30:403–5.

- Hay GH, Harper TB, Courson FH. Preparing school personnel to assist students with life-threatening food allergies. J Sch Health 1994;64(3):119–21.

- Eisenberg JD, Moe EL, Stillger CF. Educating school personnel about asthma. J Asthma 1993;30(5):351–8.

- Lurie N, Straub MJ, Goodman N, Bauer EJ. Incorporating asthma education into a traditional school curriculum. Am J Pub Health 1998;88(5):822.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Guidelines for school health programs to prevent tobacco use and addiction. MMWR 1994;43(RR-2):1–18.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Preventing tobacco use among young people: a report of the Surgeon General. MMWR 1994;43(RR-4):1–10.

- Clark NM, Brown RW, Parker E, Robins TG, Remick DG, Philbert MA. Childhood asthma. Environ Health Perspect 1999;107(3):421–9.

- Epps RP, Manley MW, Glynn TJ. Tobacco use among adolescents: strategies for prevention. Pediatr Clin North Am 1995;42(2):389–402.

- Morkjaroenpong V, Rand CS, Butz AM, Huss K, Eggleston P, Malveaux FJ. Environmental tobacco smoke exposure and nocturnal symptoms among inner-city children with asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2002;110(1):147–54.

- Eggleston PA, Bush RK. Environmental allergen avoidance: an overview. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2001;107(3):S403–5.

- Dautel PJ, Whitehead L, Tortolero S, Abramson S, Sockrider MM. Asthma triggers in the elementary school environment: a pilot study. J Asthma 1999;36(8):691–702.

- Tortolero SR, Bartholomew LK, Tyrrell S, Abramson SL, Sockrider MM, Markham CM. Environmental allergens and irritants in schools: a focus on asthma. J Sch Health 2002;72(1):33–8.

- Campbell ME, Dwyer JJ, Goettler F, Ruf F, Vittiglo M. A program to reduce pesticide spraying in the indoor environment: evaluation of the “Roach Coach” Project. Can J Public Health 1999;90(4):277–81.

- Greene A, Breisch NL. Measuring integrated pest management programs for public buildings. J Econ Entom 2002;95(1):1013.

- Herfurt D. Exercise and EIA. J Respir Care Practitioners 1997; 10(3):42–8.

- Block ME, Garcia C, eds. Including students with disabilities in regular physical education. Reston, Virginia: National Association for Sport and Physical Education, American Association for Active Lifestyles and Fitness, 1995.

- Gean J, Schroth MK, Lemanske RF. Childhood asthma: older children and adolescents. Clin Chest Med 1995;16(4):657–70.

- Howenstine MS, Eigen H. Medical care of the adolescent with asthma. Adolesc Med 2000;11(3):501–19.

- Kumar A, Busse WW. Recognizing and controlling exercise-induced asthma. J Respir Dis 1995;16(12):1087–96.

- Majer LS. Managing patients who have asthma: the pediatrician and the school. Pediatr Rev 1993;14(10):391–4.

- Einhorn E, DiMaio M. An interdisciplinary program to control pediatric asthma. Continuum May–June 2000;8–13.