Acanthocephaliasis

[Macracanthorhynchus ingens] [Bolbosoma spp.] [Macracanthorhynchus hirudinaceus] [Moniliformis moniliformis]

Causal Agents

Acanthocephala (also known as spiny- or thorny-headed worms) are common parasites of wildlife and some domestic animal species, but they rarely infect humans. Species recovered from humans include Macracanthorynchus hirudinaceus, Macracanthorynchus ingens, Moniliformis moniliformis, Acanthocephalus rauschi, Pseudoacanthocephalus bufonis, Corynosoma strumosum, and Bolbosoma sp. M. hirudinaceus and M. moniliformis are the most common species implicated in human infections.

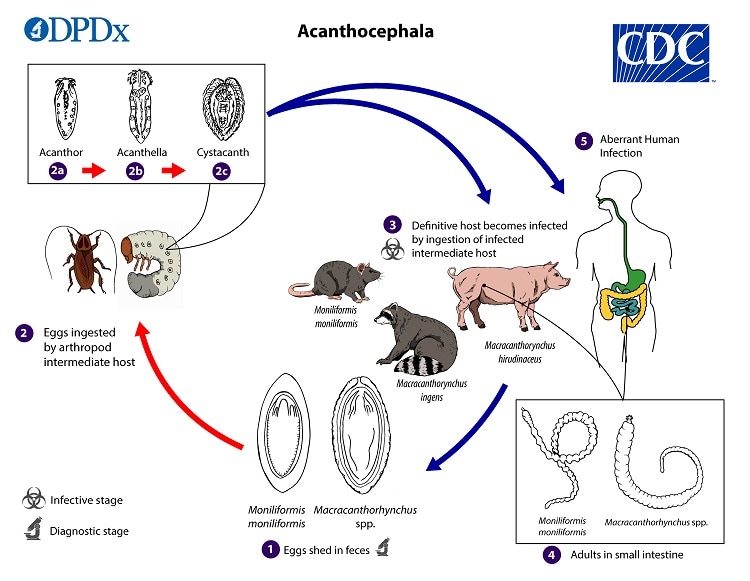

Life Cycle

Eggs are shed in the feces of the definitive hosts  . The eggs contain a fully developed acanthor when shed in feces. The eggs are ingested by an intermediate host

. The eggs contain a fully developed acanthor when shed in feces. The eggs are ingested by an intermediate host  , which is always an insect. Within the hemocoelom of the insect, the acanthor

, which is always an insect. Within the hemocoelom of the insect, the acanthor  molts into a second larval stage, called an acanthella

molts into a second larval stage, called an acanthella  . After 6–12 weeks, the worm reaches the infective stage called a cystacanth

. After 6–12 weeks, the worm reaches the infective stage called a cystacanth  . The definitive host becomes infected upon ingestion of intermediate hosts containing infective cystacanths

. The definitive host becomes infected upon ingestion of intermediate hosts containing infective cystacanths  . In the definitive host, liberated juveniles attach to the wall of the small intestine, where they mature

. In the definitive host, liberated juveniles attach to the wall of the small intestine, where they mature  and mate in about 8–12 weeks. In humans

and mate in about 8–12 weeks. In humans  the worms seldom develop to full maturity or produce eggs.

the worms seldom develop to full maturity or produce eggs.

Hosts

Natural definitive hosts include rats (Moniliformis moniliformis), swine (Macracanthorynchus hirudinaceus), and raccoons (Macracanthorynchus ingens). The insect intermediate host varies by species but is usually scarabaeoid or hydrophilid beetles for M. hirudinaceus and likely M. ingens, and beetles or cockroaches for M. moniliformis.

Geographic Distribution

Acanthocephala are widely distributed. Cases of acanthocephaliasis more commonly occur in areas where insects are eaten for dietary or medicinal purposes or in children who consume insects. Macracanthorynchus hirudinaceus is found wherever wild or domestic swine occur. Macracanthorynchus ingens is highly endemic in raccoons from the southeastern United States, and the recorded human cases originate from Texas and Florida. The distribution of Moniliformis moniliformis is not known but is likely cosmopolitan.

Clinical Presentation

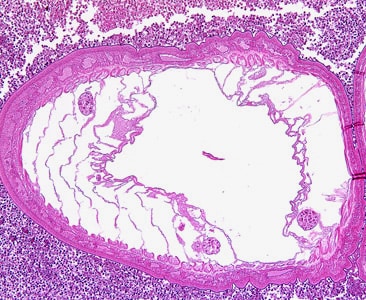

Clinical symptoms of acanthocephaliasis are often severe, due in part to the mechanical damage caused by the insertion of the armed proboscis into the lumen of the host’s intestine. Symptoms generally include abdominal pain and related digestive complaints. However, low-intensity or early infections may be asymptomatic.

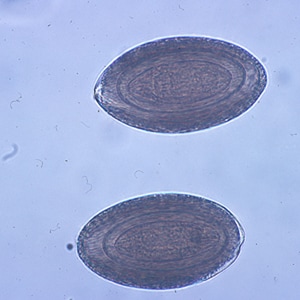

Eggs of Macracanthorhynchus sp.

Macracanthorhynchus sp. eggs are 80–100 µm long by 50 µm wide. They are ovoid and have a thick, dark brown shell that is textured. Eggs are shed in feces and contain a larva (acanthor) that possesses rostellar hooks. When adults do reach maturity in the human host, they rarely produce eggs, so eggs are not usually found in the feces of infected humans.

Eggs of Moniliformis moniliformis.

Moniliformis moniliformis eggs are 90–125 µm long by 65 µm wide. They are elongate-oval and have a thick, clear shell. Eggs are shed in feces and contain a larva (acanthor) that possesses rostellar hooks. The normal definitive hosts for M. moniliformis are rodents, including rats. Adults seldom mature in the human host. When adults do reach maturity in the human host, they rarely produce eggs, so eggs are not usually found in the feces of infected humans.

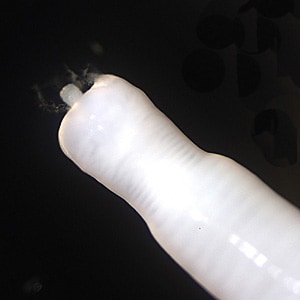

Adults of Macracanthorhynchus hirudinaceus.

Adults of Macracanthorhynchus hirudinaceus are large pseudocoelomates that vary in color from milky-white to pinkish to reddish. The body typically has a wrinkled appearance, giving the illusion of segmentation (pseudosegmentation). Adult females measure 18–65 cm long by 4–10 mm wide; adult males measure 5–10 cm long by 3–5 mm wide. The proboscis contains 5 or 6 rows of recurved hooks. Adults reside in the intestine of the definitive host, which is usually a pig. In humans, the worms seldom mature and when they do, rarely produce eggs.

Adults of Moniliformis moniliformis.

Adults of Moniliformis moniliformis are large pseudocoelomates that are pseudosegmented and chalky-white in color. Adult females measure 10−30 cm long by 1.25–1.5 mm wide; adult males measure 4–10 cm long. The cylindrical proboscis contains 12–15 spiral rows of recurved hooks. Adults reside in the intestine of the definitive hosts, which are usually rodents.

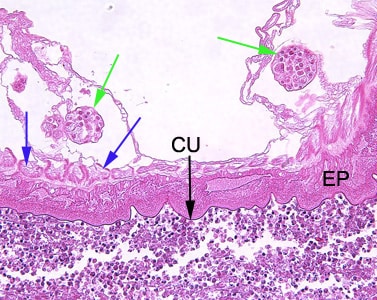

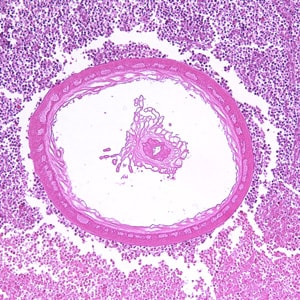

Acanthocephalans in tissue, stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E).

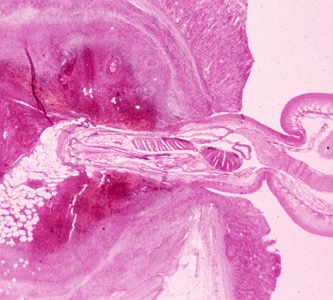

Intermediate hosts of acanthocephalans.

Acanthocephalans require an invertebrate as an intermediate host, which can include crustaceans, insects, and annelids. The intermediate host for Macracanthorhynchus hirudinaceus is usually a scarabaeoid or hydrophilid beetle; M. ingens is known to use woodroaches. The intermediate host for Moniliformis moniliformis is usually a cockroach or beetle. The intermediate hosts for Bolbosoma spp. are microcrustacea, with fish serving as paratenic hosts. Humans usually become infected with acanthocephalans by ingesting infected intermediate or paratenic hosts.

Laboratory Diagnosis

Diagnosis is made by the observation of eggs or adults in stool. As humans are not the usual definitive host for acanthocephalans, the parasites often do not reach sexual maturity and produce eggs. Eggs in feces, especially in the absence of other symptoms, may indicate spurious passage.

Laboratory Safety

Standard laboratory safety protocols apply. Acanthocephalan eggs are not infectious to humans.

Suggested Reading

Mathison, B.A., Bishop, H.S., Sanborn, C.R., dos Santos Souza, S. and Bradbury, R., 2016. Macracanthorhynchus ingens Infection in an 18-Month-Old Child in Florida: A Case Report and Review of Acanthocephaliasis in Humans. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 63(10), pp.1357–1359.

DPDx is an educational resource designed for health professionals and laboratory scientists. For an overview including prevention, control, and treatment visit www.cdc.gov/parasites/.