Community Engagement in Health-Related Research: A Case Study of a Community-Linked Research Infrastructure, Jefferson County, Arkansas, 2011–2013

COMMUNITY CASE STUDY — Volume 12 — July 23, 2015

M. Kathryn Stewart, MD, MPH; Holly C. Felix, PhD, MPA; Mary Olson, DMin; Naomi Cottoms, MA; Ashley Bachelder, MPH, MPS; Johnny Smith; Tanesha Ford, MA; Leah C. Dawson, MS; Paul G. Greene, PhD

Suggested citation for this article: Stewart MK, Felix HC, Olson M, Cottoms N, Bachelder A, Smith J, et al. Community Engagement in Health-Related Research: A Case Study of a Community-Linked Research Infrastructure, Jefferson County, Arkansas, 2011–2013. Prev Chronic Dis 2015;12:140564. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5888/pcd12.140564external icon.

PEER REVIEWED

PEER REVIEWED

Abstract

Background

Underrepresentation of racial minorities in research contributes to health inequities. Important factors contributing to low levels of research participation include limited access to health care and research opportunities, lack of perceived relevance, power differences, participant burden, and absence of trust. We describe an enhanced model of community engagement in which we developed a community-linked research infrastructure to involve minorities in research both as participants and as partners engaged in issue selection, study design, and implementation.

Community Context

We implemented this effort in Jefferson County, Arkansas, which has a predominantly black population, bears a disproportionate burden of chronic disease, and has death rates above state and national averages.

Methods

Building on existing community–academic partnerships, we engaged new partners and adapted a successful community health worker model to connect community residents to services and relevant research. We formed a community advisory board, a research collaborative, a health registry, and a resource directory.

Outcome

Newly formed community–academic partnerships resulted in many joint grant submissions and new projects. Community health workers contacted 2,665 black and 913 white community residents from December 2011 through April 2013. Eighty-five percent of blacks and 88% of whites were willing to be re-contacted about research of potential interest. Implementation challenges were addressed by balancing the needs of science with community needs and priorities.

Interpretation

Our experience indicates investments in community-linked research infrastructure can be fruitful and should be considered by academic health centers when assessing institutional research infrastructure needs.

Background

Racial disparities in health and health care quality are well documented (1). An important barrier to addressing such disparities is low levels of research participation among those groups that experience disparities in illness and death rates (2). This imbalance in research creates challenges in understanding and developing strategies to address the causes of disparities (3). Multiple factors have been identified as affecting minority participation in research, including lack of trust, power differences, limited access to health care and research opportunities, participant burden, and lack of perceived relevance (2–6). Community engagement has been identified as a way to address these factors. True engagement of underrepresented communities is facilitated by intentional structural supports such as establishing community advisory boards, developing financial and other resources, involving minority researchers, hiring community health workers, sharing resources with community partners, and using community-based participatory research approaches (7–9). We describe an enhanced model of community engagement in which we developed a community-linked research infrastructure to involve minorities in research both as participants and as partners engaged in issue selection, study design, and implementation.

Community Context

This community-linked research infrastructure (infrastructure) was implemented in Jefferson County, Arkansas, which has a predominantly black population (55.6%), bears a disproportionate burden of chronic illness, and has disease and death rates exceeding state and national averages (Table 1).

Methods

The infrastructure, funded from 2010 through 2013 by the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities, deployed intentional structural supports identified in the literature as facilitating true community engagement (7,8). An existing long-term community–academic partnership between the Fay W. Boozman College of Public Health (the College), University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences (UAMS), and Tri-County Rural Health Network (Tri-County) developed the grant proposal to build community infrastructure for engaging minorities in research. As such, all infrastructure activities focused on this overall community engagement goal rather than on engagement in a specific program to address a particular health issue.

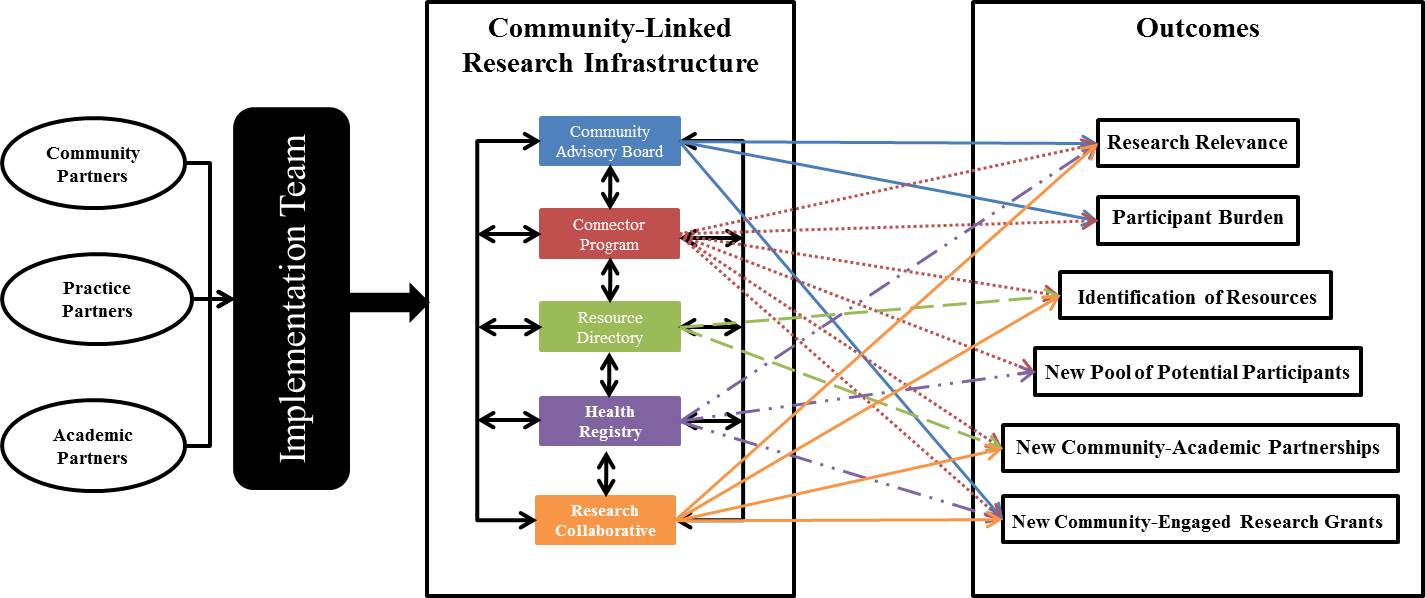

Intentional structural supports designed for the infrastructure consisted of an implementation team; a community advisory board to advise on infrastructure activities; the Community Health and Research Connector Program (connector program) staffed by local community health workers, called “connectors,” to address cultural, social, and community factors affecting access to and use of health-related resources (eg, social services, medical care, research opportunities); a health registry to provide the community advisory board with input from a large segment of the community regarding health needs and use of health-related resources; a resource directory to facilitate community access to health-related resources; and a research collaborative to solicit ideas on research priorities from community organizations. Tri-County conducted community forums to engage communities in dialogue about research relevant to health disparities. Forums and community advisory board meetings identified concerns about disparities in chronic disease, lack of health resources, and sociocultural barriers to health care and health care use that defined the focus of the infrastructure. The Figure illustrates the contributions the implementation team made to develop and deliver the main components of the infrastructure and the associated outcomes that the components were conceptualized to affect. The UAMS institutional review board reviewed all infrastructure activities and determined that the service activities of the connector program did not constitute research.

Figure. Conceptual framework of the infrastructure. [A text version of this figure is also available.]

The figure presents a conceptual framework to depict 1) the composition of the implementation team, 2) components of the infrastructure, and 3) which outcomes each component was to contribute to and influence. The figure shows these 3 sections, respectively, from left to right with arrows between each. Section 1 shows 3 circles labelled Community Partners, Practice Partners, and Academic Partners with an adjoining line and arrow that points to a box labeled Implementation Team. The Implementation Team box connects to Section 2. Section 2 is titled Community-Linked Research Infrastructure and lists the following infrastructure components, each in a different box, in a vertical line. From top to bottom they read: Community Advisory Board, Connector Program, Resource Directory, Health Registry, and Research Collaborative. Each component is connected by 2-sided arrows that draw a line between all the components to illustrate their interconnectedness and to signify that they all function at the same time. Each component also has 2 to 5 matching 1-sided arrows that point to the right to various outcomes listed in Section 3. Community Advisory Board arrows connect to Research Relevance, Participant Burden, and New Community-Engaged Research Grants. Connector Program arrows connect to Research Relevance, Participant Burden, Identification of Resources, New Pool of Potential Participants, New Community–Academic Partnerships, and New Community-Engaged Research Grants. Resource Directory arrows connect to Identification of Resources and New Community–Academic Partnerships. Health Registry arrows connect to Research Relevance, New Pool of Potential Participants, and New Community-Engaged Research Grants. Research Collaborative arrows connect to Research Relevance, Identification of Resources, New Community–Academic Partnerships, and New Community-Engaged Research Grants. Section 3 is titled Outcomes and lists the following outcomes in boxes in a vertical line. From top to bottom they read: Research Relevance, Participant Burden, Identification of Resources, New Pool of Potential Participants, New Community–Academic Partnerships, and New Community-Engaged Research Grants. The arrows in Section 2 indicate an influence and association with the infrastructure components.

The objectives of the infrastructure were to hire and train local community health workers, contact at least 1,200 community residents, document residents’ health concerns and conditions, assess residents’ interest in health-related service programs and research projects, link residents to health-related resources, and facilitate minority community–academic research partnerships. We report on challenges addressed and short-term successes in designing and deploying this community engagement infrastructure.

Intentional structural supports

Implementation team. The implementation team of grassroots, academic, and health practice community members included representatives from Tri-County, Shiloh Baptist Church, the College, and the UAMS South Central Regional Program in Jefferson County (South Central) ( Table 2). In addition to managing overall efforts, the team facilitated community-partnered research by introducing community partners to noninfrastructure researchers with expertise related to health issues prioritized by the community and by soliciting interest from researchers with expertise in responding to community concerns.

Community advisory board. The 8-member community advisory board was established to integrate the voice of the grassroots community into infrastructure design and implementation. Community partners on the implementation team invited selected community residents and representatives of community organizations with personal experience and knowledge of health and social issues in Jefferson County to serve on the community advisory board. Advisory board members received training on community-based participatory research and health disparities before being asked to sign a memorandum of understanding outlining their commitment to the infrastructure and the benefits of participation. Members were paid an honorarium to recognize their contributions in quarterly meetings.

Community Health and Research Connector Program. The connector program was designed as a public service provided by connectors to directly engage community residents and facilitate their access to and use of health-related resources, including both services and research opportunities. This program was adapted from another community health worker program, called the Community Connector Program, which successfully promoted use of community-based long-term care services as a cost-effective alternative to institutional care (12).

The connector program aimed to serve 1,200 minority and low-income community residents. Research participation was not required for assistance from connectors. Connectors were responsible for administering the registry questionnaire to document health needs and research interests, sustaining contact with community residents to develop trust and bi-directional interaction, facilitating connections to needed resources, providing follow-up, establishing liaisons with referral sites, entering data into an electronic database, and conducting quality control procedures to maintain data integrity.

Black residents of Jefferson County were hired as connectors. Tri-County employed the connectors rather than UAMS because employment by a community organization was seen as representing community interests and built trust with community residents. This strategy allowed us to allocate salary support for connectors to the Tri-County subcontract consistent with efforts to build financial support for community organizations and jobs to strengthen the local economy.

Community and academic partners shared responsibility for training the connectors. Tri-County assumed primary responsibility for training on civic rights and responsibilities, leadership, interpersonal communication, first impressions, understanding and processes for reaching the community, cultural and linguistic competence, safety, needs assessments, conducting forums, and developing resource directories. Researchers from the College took the lead in training on community-based participatory research and health disparities and on data collection, data entry, and quality control. Connectors also became certified in Human Subjects Protection in Research through the Office for Human Research Protections of the US Department of Health and Human Services and the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA).

Connectors engaged community members by helping them access community services: primary and specialty care, prescription assistance, and post-hospitalization follow-up; financial support for utilities, food, and housing; and assistance with re-entry into society from prison. Connectors primarily made contact with community members through regular visits to offices of health and social services, churches, community events, and through formal referral agreements with specific providers. For example, the connector program had an agreement with South Central to allow connectors to staff a desk in the clinic’s waiting room, providing community members with direct access to connector services. In this context of service, connectors collected community members’ contact and basic demographic information, invited them to complete the registry health questionnaire, and elicited community interest in research by asking community members whether they would be willing to be contacted about research opportunities.

Health registry. A health registry was designed to collect contact information, to monitor the health needs and interests of people served by the Connector program, to provide the community advisory board with community input regarding health status and use of health-related resources, and to monitor the connector program. Connectors collected data using both paper and electronic records. Forums and community advisory board meetings initially identified a broad scope of issues for potential inclusion in the registry health questionnaire. Academic partners selected items from validated instruments to assess these issues. Community partners reviewed proposed items and helped select those that best captured community concerns while minimizing participant burden. These items were incorporated into a draft presented to the community advisory board in a discussion of survey research methods followed by a group cognitive interviewing exercise. After input from connectors and the implementation team, the community advisory board’s feedback was incorporated into a revised version, which included 119 closed-ended items and 1 open-ended question about health concerns ( Table 3).

Resource directory. The resource directory developed by the connectors contained information about health and social services and research opportunities. Connectors developed relationships with the staff of organizations providing services and documented information in the directory to which they referred when linking community residents to needed services.

Research collaborative. We formed the research collaborative to facilitate communication, resource development, and community-engaged research. Tri-County’s executive director and South Central’s administrator co-chaired the collaborative. Other members represented the regional hospital, the local public health unit, Blue Cross Blue Shield of Arkansas, the Arkansas Department of Corrections, Shiloh Baptist Church, and the College.

Outcome

New community–academic research partnerships

The implementation team was successful in engaging minority community representatives as partners in research. The College’s researchers made introductions and invited noninfrastructure researchers to team meetings and community advisory board meetings in the community, and Tri-County followed up to explore collaborative opportunities. Eighteen researchers assisted by the infrastructure were sent a brief survey by email to assess their experiences. All reported positive interactions with the infrastructure. They had varying levels of engagement ranging from assistance in grant planning to implementation of community-engaged research. Researchers also reported how they had benefited from networking facilitated by the infrastructure and from Tri-County staff or the community advisory board chair and how connectors assisted in recruiting volunteers for their studies. Researchers reported that infrastructure community partners consulted with them about their ongoing or potential future community-engaged research projects, contributed to the development of funding proposals, and served as community co-investigators on funded grants. Connectors also served on numerous community advisory boards for researchers.

As of August 2014, the infrastructure facilitated submission of 23 grants involving more than 100 community partners and collaborating organizations and 46 researchers from 9 academic institutions. One example that included minority community partners and minority researchers introduced through the infrastructure focused on measuring trust. Other studies growing out of new partnerships involved the faith community’s work on mental health (16,17). Other research topics in grants submitted were substance abuse, social networks, sexual violence, pesticide exposure, and health literacy.

Community advisory board

The community advisory board played an active role in establishing the infrastructure’s focus on facilitating research addressing health disparities, creating the registry questionnaire, and testing use of an electronic audience response system for group administration of the questionnaire to community residents. Community advisory board members reviewed aggregated registry data to assist with data interpretation, clarify needed services, identify research issues for further study, and express concerns about risks to participants or the community.

Some community advisory board members had severe health problems that sometimes affected their level of engagement. The connector program was a critical component, because connectors often helped them meet their needs. In one case, clinicians on the implementation team and community advisory board helped a member access badly needed surgical care.

Community Health and Research Connector Program

The opportunity to link residents to services was fulfilling for those employed as connectors. However, salary support based on grant funding and an emphasis on defined procedures for data collection created challenges in retaining qualified connectors. We learned we needed to hire connectors who understood the value of research and had a strong commitment to the infrastructure. For example, one connector had had a very positive research experience herself, which enabled her to explain on a personal level why research participation is important.

The regulatory training was a challenge for some connectors who had little or no previous experience with online training. Connectors who completed the training without difficulty served as role models and tutors.

Connectors exceeded service goals by serving 2,665 black and 913 white community residents from December 2011 through April 2013. Among these residents, 85% of blacks and 88% of whites were willing to be contacted again about research that might be of interest to them.

Health registry

Barriers to completing the health questionnaire were tensions between community concerns about survey length and wording of standardized items and researchers’ interest in covering common causes of disease and death and using validated questions for comparison purposes. These tensions were addressed by facilitating community advisory board and connector input in the design phase, incorporating community-generated questions, and allowing connectors the flexibility of collecting only contact information and ascertaining community residents’ willingness to be re-contacted with or without the shorter questionnaire sections on health concerns and medical history.

Resource directory

Connectors were successful in developing relationships with referral agencies potentially able to provide residents with needed resources. Resources with the potential to influence interest in and access to preventive health care and research were assistance with rent and utility bills and enrollment in Medicaid and pharmacy assistance programs.

Transportation between Jefferson County and Little Rock, where more clinical studies are conducted, was a barrier to research participation, and although we engaged many investigators in community research partnerships, we were less successful in finding clinical studies focused on diseases of interest to community residents (eg, lupus).

Research collaborative

Research collaborative members met regularly to discuss organizational issues and concerns related to health disparities. For example, representatives from the Arkansas Department of Corrections described high rates of pregnancy among newly released female inmates, which led to collaborative efforts between the Arkansas Department of Corrections, the Jefferson County health unit of the Arkansas Department of Health, the South Central Clinic, and the connectors to facilitate access to family planning services in the community before release. In addition, regional hospital representatives discussed concerns about avoidable hospital readmissions and the possibility of a study to test use of connectors to help reduce readmissions. Toward that aim, connectors and hospital administrators established HIPAA-compliant procedures to refer patients to connectors as a routine component of hospital discharge to facilitate connector assistance.

Interpretation

This article describes a community engagement effort to increase involvement of minorities as research partners and to identify minorities in the community interested in learning about opportunities to participate in research. By implementing intentional structural supports (ie, community–academic partnerships, community advisory board, community health worker model, health registry, resource directory, research collaborative), we were able to engage the broader community in research and successfully reach populations with disproportionate health burdens. UAMS investigators, including black, white, and other minority researchers, have engaged with community organizations, and black community residents now serve as community co-investigators on new studies focused on issues of importance to the community (16,17). The adaptation of the Community Connector Program (12), the integration of institutional providers’ assistance with referrals and connections, and the community engagement approach of the infrastructure created a context in which access was increased and minorities were engaged who often are not represented in research.

Our work is instructive in the context of the efforts of others to increase minority research engagement. Chadiha et al have also reported the use of community-based participatory research, including a community advisory board, to build a research volunteer registry of senior urban blacks (18). They were able to enroll 1,273 volunteers in the registry over 7 years by recruiting at events sponsored by the health research center. At least 9 researchers successfully used their registry to recruit study participants over 5 years. In comparison, the infrastructure was able to engage a larger population of potential research participants in a shorter period, perhaps because it was more community-driven, hired local connectors through a community organization instead of relying on volunteers, and targeted both community organizations and individual residents for engagement.

The connectors were able to engage and provide information to a predominantly minority population often underrepresented in research, which encouraged the population’s interest in learning about research opportunities. Eighty-five percent of blacks and 88% of whites were willing to be contacted again about research that might be of interest to them. This finding is consistent with the review conducted by Wendler et al of 20 studies reporting consent rates by race or ethnicity. That review found few differences between blacks and whites in their willingness to participate in research and suggested that access is a greater barrier than attitudes (6).

A survey of community health worker programs in 2011 found that three-fourths of respondents were involving community health workers in research activities; 39% of respondents reported involvement of community health workers in research recruitment (19). A more recent multisite study conducted by Cottler and colleagues at 7 Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSA) Sentinel Network sites found blacks were more willing than other racial groups to participate in research, even when it required obtaining blood samples (20). That study, like the infrastructure, hired community health workers to engage residents directly, and the authors concluded that the workers were crucial to research success. The community health workers were hired by the institutional members of the CTSA Sentinel Network and focused on direct engagement of potential participants rather than building partnerships with the organizations by which they are served to be sure they did not “bypass the input of community members or inadvertently privilege the perceptions of community leaders and service providers” (20). Although this approach may be effective in recruiting people for clinical trials and avoiding censoring and interpretation of community residents’ research interests by organizational gatekeepers, engagement at both individual and organizational levels allowed the infrastructure to facilitate development of new community–academic partnered studies and programs and engage minority investigators in community-engaged research while also identifying individual-level interest in research.

Although both the infrastructure and the Sentinel Network successfully engaged minorities in research through the work of community health workers, sustainability of interventions employing community health workers has traditionally been a challenge. Research infrastructure funding, such as CTSA resources or research center grants, is potentially an ideal source of support for community health workers. Although the grant period that supported the development of the infrastructure is complete, Tri-County managed to continue support for some of their connectors through grants on which they are partners. New organizational partnerships facilitated through the infrastructure will likely continue well into the future. We believe our experience with the infrastructure indicates that investments in community-based research infrastructure should be considered by academic health centers when assessing institutional research infrastructure needs.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the connectors, the members of the research collaborative and of the community advisory board, and the technical support of the registry received from the UAMS Translational Research Institute’s Comprehensive Informatics Resource Center. We also express our appreciation to Dr Robert Price, Assistant Director of Regional Programs for Research, for his support as our practice partner in the infrastructure. This work was supported by NIH grant no. A1-37154-01, NIH CTSA grant no. 8UL1TR000039, and Arkansas Prevention Research Center, Center for Disease Control and Prevention Grant no. U48 DP001943.

Author Information

Corresponding Author: M. Kathryn Stewart, MD, MPH, Fay W. Boozman College of Public Health, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, 4301 West Markham St, Slot 820, Little Rock, AR 72205. Telephone: 501-526-6625. Email: stewartmaryk@uams.edu.

Author Affiliations: Holly C. Felix, Ashley Bachelder, Leah C. Dawson, Paul G. Greene, Fay W. Boozman College of Public Health, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, Little Rock, Arkansas; Mary Olson, Naomi Cottoms, Tri County Rural Health Network, Inc, Helena, Arkansas; Johnny Smith, Shiloh Baptist Church and Ten Thousand Black Men, Pine Bluff, Arkansas; Tanesha Ford, University of Arkansas at Pine Bluff, Pine Bluff, Arkansas.

References

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. 2013 National Healthcare Disparities Report. Rockville (MD): US Department of Health and Human Services; 2014. AHRQ Publication No. 12-0006. http://www.ahrq.gov/research/findings/nhqrdr/nhdr13/2013nhdr.pdf. Accessed November 26, 2014.

- Yancey AK, Ortega AN, Kumanyika SK. Effective recruitment and retention of minority research participants. Annu Rev Public Health 2006;27:1–28. CrossRefexternal icon PubMedexternal icon

- Branson RD, Davis K Jr, Butler KL. African Americans’ participation in clinical research: importance, barriers, and solutions. Am J Surg 2007;193(1):32–9; discussion 40. CrossRefexternal icon PubMedexternal icon

- Braunstein JB, Sherber NS, Schulman SP, Ding EL, Powe NR. Race, medical researcher distrust, perceived harm, and willingness to participate in cardiovascular prevention trials. Medicine (Baltimore) 2008;87(1):1–9. CrossRefexternal icon PubMedexternal icon

- Russell KM, Maraj MS, Wilson LR, Shedd-Steele R, Champion VL. Barriers to recruiting urban African American women into research studies in community settings. Appl Nurs Res 2008;21(2):90–7. CrossRefexternal icon PubMedexternal icon

- Wendler D, Kington R, Madans J, Van Wye G, Christ-Schmidt H, Pratt LA, et al. Are racial and ethnic minorities less willing to participate in health research? PLoS Med 2006;3(2):e19. CrossRefexternal icon PubMedexternal icon

- Terpstra J, Coleman KJ, Simon G, Nebeker C. The role of community health workers (CHWs) in health promotion research: ethical challenges and practical solutions. Health Promot Pract 2011;12(1):86–93. CrossRefexternal icon PubMedexternal icon

- Minkler M, Wallerstein N, editors. Community-based participatory research for health: from process to outcomes. 2nd edition. San Francisco (CA): Jossey-Bass; 2008.

- Shalowitz MU, Isacco A, Barquin N, Clark-Kauffman E, Delger P, Nelson D, et al. Community-based participatory research: a review of the literature with strategies for community engagement. J Dev Behav Pediatr 2009;30(4):350–61. CrossRefexternal icon PubMedexternal icon

- US Census Bureau. American Community Survey; 2013. http://factfinder.census.gov/faces/nav/jsf/pages/searchresults.xhtml?refresh=t. Accessed February 23, 2015.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. CDC WONDER: about underlying cause of death 1999–2013. http://wonder.cdc.gov/ucd-icd10.html. Accessed February 23, 2015.

- Felix HC, Mays GP, Stewart MK, Cottoms N, Olson M. The care span: Medicaid savings resulted when community health workers matched those with needs to home and community care. Health Aff (Millwood) 2011;30(7):1366–74. CrossRefexternal icon PubMedexternal icon

- Stewart MK, Felix HC, Cottoms N, Olson M, Shelby B, Huff A, et al. Capacity building for long-term community-academic health partnership outcomes. Int Public Health J 2013;5(1):115–28. PubMedexternal icon

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 2012. http://www.cdc.gov/brfss/. Accessed June 16, 2015.

- National Cancer Institute. Health Information National Trends Survey. http://hints.cancer.gov/. Accessed June 16, 2015.

- Sullivan G, Hunt J, Haynes TF, Bryant K, Cheney AM, Pyne JM, et al. Building partnerships with rural Arkansas faith communities to promote veterans’ mental health: lessons learned. Prog Community Health Partnersh 2014;8(1):11–9. CrossRefexternal icon PubMedexternal icon

- Yeary K, Bryant K, Haynes T, Turner J, Smith J, Kuo D, et al. Community exchange of “best practices” to conduct a multi-level, mixed methods health assessment across two counties: Faith-Academic Initiative for Transforming Health (FAITH) in the Delta. Proceedings of the 2014 Annual Meeting of the American Public Health Association, New Orleans, Louisiana, November 15–19, 2014.

- Chadiha LA, Washington OGM, Lichtenberg PA, Green CR, Daniels KL, Jackson JS. Building a registry of research volunteers among older urban African Americans: recruitment processes and outcomes from a community-based partnership. Gerontologist 2011;51(Suppl 1):S106–15. CrossRefexternal icon PubMedexternal icon

- Felix HC, Lee D, Stewart MK, Greene PG. Engagement of community health workers in the research enterprise: a survey of organizations and the research roles given CHWs. Journal of Community Engagement and Higher Education 2013;5(1):13–23.

- Cottler LB, McCloskey DJ, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Bennett NM, Strelnick H, Dwyer-White M, et al. Community needs, concerns, and perceptions about health research: findings from the clinical and translational science award sentinel network. Am J Public Health 2013;103(9):1685–92. CrossRefexternal icon PubMedexternal icon

Tables

Table 1. Sociodemographic Characteristics and Selected Health Indicators, Jefferson County, Arkansas, Arkansas State, and United States

Table 1. Sociodemographic Characteristics and Selected Health Indicators, Jefferson County, Arkansas, Arkansas State, and United States

| Characteristic or Indicator | Jefferson County | Arkansas | United States |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic indicators, 2009–2013 (10) | |||

| Total population | 73,191 | 2,958,765 | 318,857,056 |

| White, % | 41.8 | 79.9 | 77.7 |

| Black, % | 55.6 | 15.6 | 13.2 |

| Bachelor’s degree or higher, % | 17.5 | 20.1 | 28.8 |

| Median household income, $ | 37,140 | 40,768 | 53,046 |

| Annual average unemployment rate, % | 13.4 | 8.9 | 9.7 |

| Population under federal poverty level, % | 23.9 | 19.2 | 15.4 |

| Households with single parent, % | 22.5 | 18.0 | 17.9 |

| Health indicators, age adjusted rates per 100,000, 1999–2013 (11) | |||

| Overall mortality, all causes | 1,080.3 | 1,017.3 | 823.5 |

| Cancer mortality rate among blacks | 236.1 | 245.8 | 222.0 |

| Cancer mortality rate among whites | 206.4 | 202.0 | 185.2 |

| Heart disease mortality rate among blacks | 315.7 | 304.2 | 262.9 |

| Heart disease mortality rate among whites | 287.6 | 239.3 | 205.4 |

Table 2. Implementation Team, Case Study of a Community-Linked Research Infrastructure, Jefferson County, Arkansas, December 2011–April 2013

Table 2. Implementation Team, Case Study of a Community-Linked Research Infrastructure, Jefferson County, Arkansas, December 2011–April 2013

| Organization | Project Purpose |

|---|---|

| Community partners | |

| Tri-County Rural Health Network (Tri-County) | Nonprofit community-based organization with mission of improving access to health care. Tri-County’s primary initiative was the original Community Connector Program (12) adapted for the infrastructure. The original Community Connector Program deploys community health workers to connect people with long-term care needs to home- and community-based care by addressing socio -cultural barriers, establishing trust, and increasing access through system navigation. Medicaid now funds the original Community Connector Program based on cost savings generated through decreased use of institutional care (12). Tri-County was represented on the implementation team by its community engagement specialist. The executive director served on the community advisory board and co-chaired the research collaborative. |

| Shiloh Baptist Church | The pastor of Shiloh Baptist Church also directs a community-based organization in Jefferson County that supports the education, health, and employment of black men. He served on the implementation team, chaired the community advisory board, and was a member of the research collaborative. |

| Academic partner | |

| Fay W. Boozman College of Public Health (the College), University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences (UAMS) | Faculty brought expertise in community-based participatory research, prevention and management of chronic illness, health disparities, research ethics, and program evaluation and the College’s long-term relationship with Tri-County Rural Health Network (13). The faculty was represented on the implementation team. |

| Practice partner | |

| UAMS South Central Regional Program in Pine Bluff, Jefferson County (South Central) | Local clinical resource with a community health clinic and a family practice residency program where medical, nursing, pharmacy, and allied health professionals also train. South Central was represented on the implementation team and the administrator co-chaired the research collaborative. |

Table 3. Health Registry Questionnaire, Case Study of a Community-Linked Research Infrastructure, Jefferson County, Arkansas, December 2011–April 2013

Table 3. Health Registry Questionnaire, Case Study of a Community-Linked Research Infrastructure, Jefferson County, Arkansas, December 2011–April 2013

| Domain | Number of Items | Source of Items |

|---|---|---|

| Health concerns | 1 open-ended and 14 pre-coded | Community partners |

| Medical history | 23 | BRFSS (14) |

| Cancer screening | 8 | |

| Service use | 6 | |

| Stressors | 6 | |

| Diet, exercise, tobacco use | 19 | |

| Healthcare quality | 8 | |

| Sociodemographic characteristics | 7 | |

| Research participation | 26 | HINTS (15); implementation team |

| Permission to recontact | 2 | Implementation team |

Abbreviation: BRFSS, Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System.

The opinions expressed by authors contributing to this journal do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, the Public Health Service, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, or the authors’ affiliated institutions.