Career Lieutenant Dies After Being Trapped in the Attic After Falling Through a Roof While Conducting Ventilation – Texas

Death in the Line of Duty…A summary of a NIOSH fire fighter fatality investigation

Death in the Line of Duty…A summary of a NIOSH fire fighter fatality investigation

F2011-20 Date Released: June 27, 2012

Executive Summary

On August 14, 2011, a 41-year-old career lieutenant died after falling through a roof and being trapped in an attic. The lieutenant was part of a two-man crew attempting to perform vertical ventilation of a two story multi-family apartment complex. The fire department had responded to multiple fires over the years at this apartment complex. The roof decking material was over 30 years old and would not meet the current building code. The fire on the first floor was quickly brought under control but had spread into the attic along the exterior wall and through the eaves. The fire had compromised the structural integrity of the roof decking material prior to the crew operating on the roof. When the lieutenant crossed over the peak of the roof to ventilate above the fire, he fell through the weakened roof and into the attic. His legs went through the ceiling of the second floor apartment while his body remained in the attic. He was wearing his self-contained breathing apparatus (SCBA) but was not wearing his facepiece and was overcome by the products of combustion. He was rescued by crews operating at the scene and transported to a local hospital where he died from his injuries.

Contributing Factors

- Hazard assessment/recognition

- Structural roof component-damage from previous fire

- PPE use

- Non-sprinkled building.

Key Recommendations

- ensure that the incident commander conducts an initial size-up and risk assessment of the incident scene as outlined in NFPA 1500 before beginning fire fighting operations and continually evaluates the conditions to determine if operations should become defensive

- ensure that the incident commander establishes a command post, maintains the role of director of fireground operations, does not pass command to an officer not on scene, and does not become involved in fire-fighting operations

- enforce existing standard operating procedures (SOPs) for structural fire fighting, including the use of self-contained breathing apparatus (SCBA) while conducting roof ventilation operations

- ensure that a rapid intervention team (RIT) is established and available to immediately respond to emergency rescue incidents

Additionally, municipalities, building code officials, and authorities having jurisdiction should

- develop a questionnaire or checklist to obtain building information so that the information is readily available to central dispatch if an incident is reported at the noted address

- consider requiring apartment complexes and associated multiple-family dwellings that have been “retrofitted” into current structural building code requirements also be brought up to current codes for such things as sprinkler systems and adequate structural roof members when requests for permits are made.

Introduction

On August 14, 2011, a 41-year-old career lieutenant died after falling through the roof while conducting ventilation on a multi-family apartment building at this complex.

On August 15, 2011, the U.S. Fire Administration notified the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health of this incident. On August 15-19, 2011, two Safety and Occupational Health Specialists and the Project Officer from the NIOSH Fire Fighter Fatality Investigation and Prevention Program traveled to Texas to investigate this incident. Meetings were conducted with the state fire marshal’s office, fire department, and the city code officials. Interviews were conducted with fire fighters and officers who were involved with this incident. The NIOSH investigators reviewed witness statements, dispatch logs, and the death certificate. The incident site was visited and photographed.

Fire Department

This career department consists of 1,750 members operating out of 56 stations. The stations serve a population of more than 1,200,000 people in a geographic area of approximately 370 square miles.

Staffing and Response

The staffing on both an engine and a truck is four fire fighters including an officer.

Training and Experience

The state of Texas requires 640 total hours of training for a fire fighter to receive Texas Fire Fighter certification. The fire department involved in this incident requires potential candidates for employment as a Fire & Rescue Officer to have a high school diploma or GED and 45 hours of college credit. The military equivalency for education to be considered for employment requires 4 years of service with an honorable discharge.

Victim

The victim had more than 17 years of experience and had completed a five month recruit fire training program in 1994 that encompassed more than 35 courses and 640 hours of classroom, hands-on, and ride-along training. Courses included: Fire Science, Fire Fighter Safety, Building Construction, Save Your Own/Rescue, and Self-Contained Breathing Apparatus (SCBA). In addition, he had also completed Introduction to Incident Command (ICS 100) and National Incident Management System (IS-700) training.

Incident Commander

The Battalion Chief had more than 28 years of experience and had completed training in courses such as: Fire Science, Emergency Medical Technician, Level II Instructor, Task Force Leader for the Urban Search and Rescue Team, Hazardous Materials Operations, Managing Company Tactical Operations, Leadership III, and Fire Service Officer Development V.

Personal Protective Equipment

At the time of the incident, each fire fighter was outfitted with a full ensemble of personal protective clothing and equipment, consisting of turnout gear, nomex hood, helmet, gloves, boots, and a self-contained breathing apparatus (SCBA) and facepiece.

Each fire fighter’s SCBA contained an integrated personal alert safety system (PASS) device. This department also issues portable hand-held radios to all fire fighters.

Following the inspection by NIOSH investigators, the SCBA used by the victim was sent to the NIOSH National Personal Protective Technology Laboratory (NPPTL) for additional evaluation. The SCBA was delivered to NPPTL on November 16, 2011, and inspected on March 2, 2012. The unit was identified as a 4500-psig SCBA (NIOSH approval number TC-13F-212, 45-minute duration unit). The full SCBA evaluation report is available from NIOSH upon request.

Weather

At the time of the incident, the temperature was approximately 87°F with a high for that day of 102°F. The relative humidity was around 80%. The winds were out of the north, north east at approximately 2.5 mph.

Fire Behavior

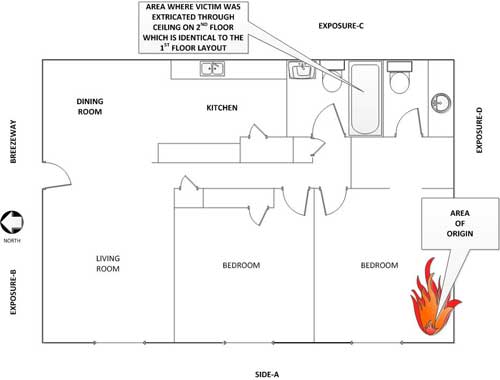

According to the arson investigator’s report, the fire originated in the electrical wiring in a first floor bedroom located at the end of a hallway. The fire was immediately called into the dispatch center and had already self-vented through a ground floor window of the first floor apartment when the first crew arrived on scene. The fire spread out the window and was channeled upward by the wooden window wells until the fire impinged on the soffit, which extended out approximately two feet from the exterior wall (see Photo 1). It then spread to the attic above the second floor apartment through the soffit.

The developing fire burning in the attic void space produced a large volume of fuel-rich excess pyrolizate and unburned products of incomplete combustion. The initial attack companies observed optically-dense smoke pushing from the first floor fire apartment. The fire and products of combustion were also spreading inside the attic space as the initial responding company made entry for suppression activities.

Photo 1. Wooden soffit above second story window where fire entered the attic from first floor room of origin located directly below.

(NIOSH photo.)

Apparatus and Arrival Times

First Alarm 1612 hours

Engine 52, arrived 1617 hours (Officer, driver/operator, fire fighter)

Engine 26, arrived 1619 hours (Officer, driver/operator, 2 fire fighters)

Engine 16, arrived 1620 hours (Officer, driver/operator, 2 fire fighters)

Truck 26, arrived 1621 hours [Officer (victim), driver/operator, 2 fire fighters]

Battalion Chief 01, arrived 1622 hours (Captain, acting, Chief Aide)

Battalion Chief 06, arrived 1622 hours (Battalion Chief, Chief Aide)

Units added to working fire

Rescue 15, arrived 1631 hours (2 paramedics)

Truck 15, arrived 1631 hours (Officer, driver/operator, 2 fire fighters)

Fire Investigation Vehicle 685, arrived 1634 hours (Officer)

Rescue 45, arrived 1640 hours (2 paramedics)

Fire Investigation Vehicle 684, arrived 1752 hours (Officer)

Structure

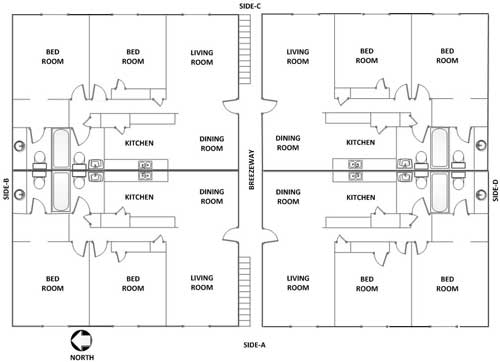

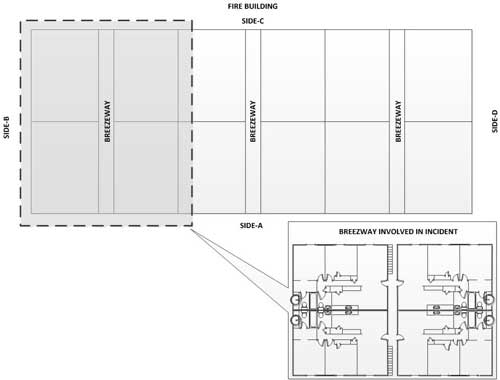

The building is a two-story, non-sprinkled, wood frame structure approximately 237 feet in length, and 50 feet wide, containing a total of 24 living units with identical floor plans. The apartment building involved in this incident consisted of two apartments on each side of a common breezeway of the two-story building. Each building had three breezeways, which situated two apartments back to back in the center section (see Diagrams 1-3). The middle apartments were separated by a fire wall that did not penetrate the roofline. The building was built in the 1970s and was ordinary, Type V construction. The exterior consists of a non-load bearing brick veneer and partial wood siding, constructed on a concrete slab foundation. The interior consisted of platform wooden construction, sheet rock covered interior walls, wooden floor joists, and lightweight two-piece trusses. The roof directly above the fire apartment was examined by the NIOSH investigators and the lightweight wooden trusses were covered with 3/8-inch plywood and asphalt shingles (see Photo 2). All 24 apartments had a common layout of approximately 1000 ft2. Fire protection features in the building are limited to single station, battery operated smoke alarms located in the hallway, in the vicinity of sleeping rooms. Means of egress from the second floor is provided by open exterior stairways constructed of steel framing, with concrete treads, positioned in a breezeway between apartment units. The building involved in this incident has had multiple fires over the years. Restorations had been made to replace just the damaged components with similar components.

Diagram 1. Ground floor apartment of origin.

Diagram 2. Typical apartment layout in relationship to breezeway.

Diagram 3. Typical building layout in relationship to breezeways.

Photo 2. Two separate pieces of roof decking. The one on the left has no fire damage and the plywood measures 3/8-inch. The one on the right was taken from the roof in the vicinity of where the victim fell through. It has minimal fire damage and shows one layer of the plywood has been compromised in several places.

(NIOSH photo.)

Investigation

On August 14, 2011, at approximately 1612 hours, central dispatch received multiple calls and dispatched an alarm for a structure fire at an apartment complex. The department has answered numerous fire calls at this location over the years. Engine 52 (E52) was the first due engine and reported on-the-scene at 1617 hours and noticed fire in a first floor window. The fire had not breached the window upon their approach. The smoke conditions were light to moderate with the smoke coming out of the A-Side (west side) of the building (see Diagram 1). E52 pulled into a parking lot adjacent to the building on B-Side. The E52 officer announced a “Quick Attack” and passed command to the next arriving officer. Note: The fire department allows the company officer who is acting as the initial incident commander to declare a quick attack to affect a rescue or protect endangered exposures. This requires passing Command via radio to an incoming company. Command was not declared by the next arriving company officer. Battalion Chief 06 assumed command upon arrival at 1622 hours approximately 5 minutes after E52. The conditions on C-Side were clear at this time. The E52 officer confirmed with the owner that everyone was out of the fire apartment. The E52 driver/operator pulled a 1 ¾-inch crosslay off of his engine for his officer and crew.

Engine 26 (E26) was the second due engine and reported on the scene at 1619 hours. E26 parked on a road that was approximately 30 yards across a lawn from the C-Side. The E26 officer noticed a small amount of fire exiting the window of the fire room on the A-Side as they drove on scene from the A/D corner. The breezeway of the fire building was full of smoke and there was some smoke emitting from the roof vents visible from C-Side.

Engine 16 (E16) was the third due engine and reported on-the-scene at 1620 hours. E16 hooked up to a hydrant and pulled in just behind E52 to supply water. The E16 officer had his fire fighter grab the second crosslay off of E52. The E16 officer looked around at the A-Side and fire was extending from the window.

The E52 crew charged their handline and prepared to make entry into the fire apartment. The door was open and pushing black smoke. They entered with moderate heat and smoked banked just below their waist. They proceeded down the hallway and encountered some fire exiting the right rear bedroom into the hallway. They opened the nozzle to cool down the hallway and then were able to make the corner and hit the seat of the fire in the bedroom immediately extinguishing any visible fire. They hit it a few more times just to ensure it did not rekindle.

During this time Truck 26 (T26) arrived on the scene at 1621 hours. The T26 officer (the victim) had his two fire fighters take a positive pressure ventilation fan to the 2nd floor doorway and then assist E16 with pulling ceilings to check for extension. During this time Battalion Chief 01(B01) and Battalion Chief 06 (B06) arrived on the scene at 1622 hours. B06, assumed Incident Command (IC), and upon arrival noticed smoke pushing from the gables and eaves of the fire building. The IC went to Side A where the fire was venting from, while the Battalion Chief’s Aide (B06A) went to Side C. B01 went to the breezeway of the fire apartment which was toward the D -Side. B01 checked for extension in the breezeway from the B-Side to the D-Side. Once on the A-Side he could see fire extending from the soffit. The E16 crew was backing up E52 and the IC noticed that the fire appeared to be out, but there was a small amount of fire extending from the soffit. The IC told E16 and E26 to search the attic on the floor above the fire for extension. The IC then told the victim to conduct vertical ventilation. The victim returned to his crew and told his driver to get a chain saw and a 28-foot extension ladder for roof ventilation. The B01A Aide assisted the T26 driver to extend the ladder to the roof at Side-C near the Side-B breezeway.

E16 and E26 entered the apartment above the fire with the second crosslay off of E52 and pike poles to search for and extinguish the fire that had extended into the attic. They encountered no heat and very little smoke. They next pulled the ceiling in the living room to the right just inside the doorway, in the hallway, and the first bedroom on the right. Only light smoke was discovered. They then pulled the ceiling in the bedroom directly over the fire room. The IC had moved upstairs and was in the bedroom at this time. They encountered moderate fire in the attic when they pulled the ceiling. It appeared to be toward the roof wall junction. They continued to pull the ceiling and hit the fire. They eventually had a hole approximately 8 feet by 8 feet. The fire appeared to cover the entire hole, but seemed to be under control. There was some confusion over assignments at this point due to the number of fire fighters inside the hallway and bedroom area, and the large volume of radio traffic.

The victim started up the ladder with the chain saw followed by his driver, who was equipped with an axe. They were going to ventilate the roof towards Side A over the seat of the fire. Note: The victim and his driver were wearing self-contained breathing apparatus but did not don their air masks during this incident. The victim and driver reached the roof on Side C and moved toward the peak of the roof towards Side A. The victim was approximately 6 to 7 feet in front of the driver when the driver dropped his axe. The smoke was intense and the driver took a couple of steps to the side to get out of the smoke and he saw the victim fall through the roof just over the peak (see Photo 3). The driver immediately rushed to the hole where the victim had fallen into the attic. He saw the chainsaw, which was still running, next to the hole where the victim fell through. He could hear the victim yelling for assistance. He laid on his stomach and reached down into the hole in an attempt to reach the victim, but was unsuccessful. He could hear crews operating in the bedroom below as he was yelling on the radio that someone had fallen through the roof. He then ran to the ladder calling on the radio that someone had fallen through the roof.

Within seconds, crews operating inside the structure found the victim’s legs protruding through the ceiling and immediately began working to free him from the attic. Members made access into the attic from the bathroom and bedroom directly above the fire in an attempt to assist the victim while crews worked to free him from the ceiling from below. The members in the attic had to abandon this tactic because they found it futile to attempt to pull the victim up. They determined that it was more efficient to free the victim from below. The victim’s removal was impeded due to him being caught on wiring and ceiling framing lumber. He was finally removed and rushed to a local hospital where he died from his injuries.

Contributing Factors

Occupational injuries and fatalities are often the result of one or more contributing factors or key events in a larger sequence of events that ultimately result in the injury or fatality. NIOSH investigators identified the following items as key contributing factors in this incident that ultimately led to the fatality:

- Hazard assessment/recognition

- Structural roof component-damage from previous fire

- PPE use

- Non-sprinkled building.

Cause of Death

The death certificate listed the cause of death as asphyxiation from the products of combustion.

Photo 3. Side-A of the gable roof where incident occurred.

(NIOSH photo.)

Recommendations

Recommendation #1: Fire departments should ensure that the incident commander conducts an initial size-up and risk assessment of the incident scene as outlined in NFPA 1500 before beginning fire fighting operations, and continually evaluates the conditions to determine if operations should become defensive.

Discussion: Among the most important duties of the first officer on the scene is conducting an initial size-up of the incident. This information lays the foundation for the entire operation. It determines the number of fire fighters and the amount of apparatus and equipment needed to control the blaze, assists in determining the most effective point of fire extinguishment attack, the most effective method of venting heat and smoke, and whether the attack should be offensive or defensive. A proper size-up begins from the moment the alarm is received and continues until the fire is under control. The size-up should also include assessments of risk versus gain throughout incident operations. 1, 2-6

The entire risk management decision making process can be summarized as follows:

- Identify or recognize

- Evaluate

- Prioritize

- Act and control

- Monitor and reevaluate

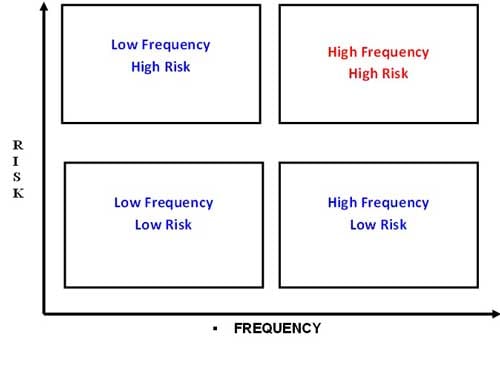

By definition, frequency is how often something does, or might, happen. Severity is a measure of the consequences if an undesirable event occurs. There are many factors that enter into the severity discussion, including cost, time lost from work, loss of use of resources, inability to deliver services, and fewer services available. Each risk will have its own set of factors that will dictate how the fire department will try to determine how severe the consequences might be.

This scale is used to establish the degree of priority (see Figure 1). Priority of the risk is in direct relation to inherent risks that have had a harmful effect on the Department and its members. The scale of high and low is used to establish the degree of risk when using frequency and severity. This approach is much more effective than accepting a high tolerance for risk which means to accept more risk. Typically with this approach frequency and severity get rated lower.

The primary focus of the risk management plan is to focus efforts on incidents, which are low frequency and high risk or severity. The reason for the focus on low frequency/high risk incidents is that these incidents do not occur on a frequent basis, but when they occur, the outcome can be harmful or detrimental to fire fighters. An example of low frequency/high risk events could be a high rise fire, technical rescue, multi-alarm fire, or conducting vertical ventilation on a structurally deficient roof.

Figure1. Frequency and risk graph.

The high frequency/high risk events occur on a regular basis or frequency and even though the risks are high or significant, these are the incidents that fire departments typically train their members to effectively mitigate. With high frequency events, there is a training and education component based upon the fire fighter’s knowledge, skills, abilities, and competencies. These incidents occur on a regular basis which allows for the fire department to develop and utilize effective standard operating procedures, proper strategy and tactics, operational risk management, and appropriate post incident analysis. This apartment complex has had multiple fires over the years and the fire department has come to know some of the inherent risks associated at this site. Training is an essential element of the process for known locations to ensure that fire fighters have the necessary competencies to recognize the proper actions to take to ensure for a successful outcome to the incident. An example would be conducting vertical ventilation on a roofing system with the sufficient structural members that had not been previously damaged by fire.

This roof ventilation operation in this incident would typically be classified as a “High Frequency/High risk” event. Fire departments around the country respond to fires in apartment complexes and conduct successful vertical ventilation on a daily basis. What made this a “Low Frequency” event is the fact that the roof decking material was not structurally sufficient to support vertical ventilation operations. The roof deck material did not meet the current codes, and what little structural integrity it provided had been compromised by not only the current fire, but also by previous fires. The roof deck was constructed in the 1970s out of 3/8 inch plywood. Modern building code requirements require roof deck material of at least ½ inch. Tactical considerations for this type of structure, and one frequented by the fire department, where fire has spread to the attic may require defensive operations.

Recommendation #2: Fire departments should ensure that the incident commander establishes a command post, maintains the role of director of fireground operations, does not pass command to an officer not on scene, and does not become involved in fire-fighting operations.

Discussion: According to NFPA 1561 Standard on Emergency Services Incident Management System, §5.3.1, “the incident commander shall have overall authority for management of the incident.”1 In addition to conducting an initial size-up, the incident commander must establish and maintain a command post outside the structure to assign companies, delegate functions, and continually evaluate the risk versus gain of continued fire-fighting efforts. In establishing a command post, the IC shall ensure the following (NFPA 1561, §5.3.7.2):

- The command post is located in or tied to a vehicle to establish presence and visibility.

- The command post includes radio capability to monitor and communicate with assigned tactical operations, command, and designated emergency traffic channels for that incident.

- The location of the command post is communicated to the communications center.

- The incident commander, or their designee, is present at the command post.

- The command post should be located in the incident cold zone.1

The use of a tactical worksheet can assist the IC in keeping track of various task assignments on the fireground. It can be used along with preplan information and other relevant data to integrate information management, fire evaluation, and decision making. The tactical worksheet should record unit status and benchmark times and include a diagram of the fireground, occupancy information, activities checklist(s), and other relevant information. The tactical worksheet can also aid the IC in continually conducting a situation evaluation and maintaining accountability.2 To effectively coordinate and direct fire-fighting operations on the scene, the IC must not become involved in fire-fighting efforts.

The practice of “Passing Command” to an officer not on the scene should not be a recommended practice. This practice assumes the second due company is really going to arrive as second due (which may not be the case – i.e. out of service, or delay arriving on scene) and any cover company may be a third or fourth due which will take far longer than expected to arrive. Further, it also assumes the second due company doesn’t get involved in a vehicle crash before arrival, or breaks down before arrival. It also assumes the second due company heard the “passing command” message and will take command upon arrival. “Passing Command” can create a gap in the command process and compromise incident management and firefighter safety. The use of “Passing Command” should be rarely applied and instead the more formalized “Transfer of Command” should be utilized to the next due or chief officer once they arrive on scene.7

A delay in establishing an effective command post may result in confusion of assignments and lack of personnel and apparatus coordination, which may contribute to rapid fire progression. The involvement of the initial IC in fire fighting also hampers the collection and communication of essential information to direct initial suppression efforts or as command is transferred to later-arriving officers.

In this incident, the first due company officer passed command to the second due officer who was not on scene. The second due officer did not assume command thinking B06 was arriving at the same time. Command was not assumed until BC06 arrived, which was five minutes after the first arriving officer. Four separate companies were on scene and operating without command direction before it was finally established. BC06 did not set up a stationary command post and ended up inside the fire building when the incident occurred. Without a command post there was no one was in charge of developing an incident action plan or managing the incoming personnel effectively. This led to some confusion over assignments and a RIT was never established.

Recommendation #3: Fire departments should ensure that fire fighters follow standard operating procedures (SOPs) for structural fire fighting, including the use of self-contained breathing apparatus (SCBA) while conducting roof ventilation operations through training, direct observation by command staff, and enforcement.

Discussion: According to the International Fire Service Training Association (IFSTA), “firefighters should never get on a roof wearing anything less than full protective clothing, SCBA, and a PASS device. . .” because of the possible presence of toxic products of combustion.4 The department in this incident has an SOP stating that SCBAs “will be worn by all personnel operating at emergency incidents above ground, below ground, or in any other area which is not, but which may become contaminated by products of combustion or other hazardous substances.” For unknown reasons, the victim and the T26 fire fighter were not on air at the time the victim fell through the roof. He was not able to don his facepiece after becoming trapped in the attic. The victim may have survived until rescuers were able to free him if he had been on air.

Recommendation #4: Fire departments should ensure that a rapid intervention team (RIT) is established and available to immediately respond to emergency rescue incidents.

Discussion: A RIT should be designated and available to respond before interior attack operations begin at all fireground operations. 1, 4, 8 The team should report to the officer in command and remain in a designated ready position until an intervention is required to rescue a fire fighter(s) or civilians. The RIT should have all tools necessary to complete the task (e.g., a search rope, first-aid kit, Haligan bar and flat-head axe combo, a resuscitator, and extra SCBA cylinders and/or transfill hoses, etc). The RIT’s only assignment should be to prepare for a rapid deployment to complete any emergency search or rescue when ordered by the IC. The RIT allows the suppression crews the opportunity to regroup and take a roll call instead of performing rescue operations. A RIT should preplan a rescue operation by finding out fire structure information (i.e., construction materials, layout, entry/egress routes, etc.), crew location and assignments, and monitoring radio traffic. When the RIT enters to perform a search and rescue, they should have full cylinders on their SCBAs and be physically prepared. When a RIT is used in an emergency situation, an additional RIT should be put into place in case an additional emergency situation arises 1

In this incident a dedicated rescue crew was never employed and no crews were held outside in standby or rescue mode. Once it was realized that a fire fighter was trapped in the attic, a fresh, well-rested RIT team with specialized rescue training could have intervened and may have had the necessary tools to rescue the victim.

Recommendation #5: Municipalities, building code officials, and authorities having jurisdiction should develop a questionnaire or checklist to obtain building information so that the information is readily available to central dispatch if an incident is reported at the noted address.

Discussion: An effective dispatch system is a key factor in fire department operations. The central dispatch center is used for receiving notification of emergencies, alerting personnel and equipment, coordinating the activities of the units engaged in emergency incidents, and providing non-emergency communications for the coordinating fire departments.9, 10 Municipalities and local authorities having jurisdiction should develop a questionnaire or checklist to ensure that central dispatch has pertinent information on a reported address. The questionnaire or checklist could focus on building characteristics including the type of construction, materials used, occupancy, fuel load, roof and floor design, sprinkler systems, and unusual or distinguishing characteristics. Municipalities and local authorities having jurisdiction should also include experienced fire personnel throughout any code or checklist developmental process concerning life safety to the public and fire department members. The information covered on this questionnaire could possibly be gathered through local contractors obtaining a permit or building owners applying for a fire fee. Once obtained, this information should be recorded, shared with other departments who provide mutual aid, and if possible, entered into the dispatcher’s computer so that the information is readily available if an incident is reported at the noted address.

Typically, pre-incident planning focuses on commercial buildings and the specific hazards they have due to their size, construction, and contents. Fire departments usually do not have the manpower or authority to conduct pre-planning of private structures in their jurisdiction. Apartment complexes and associated multiple-family dwellings that are “retrofitted” into current building codes pose a very hazardous condition to the occupants and first responding personnel.

The apartment complex involved in the incident has had multiple fires that have required significant renovations including roof repairs due to fire damage. If any inspection was conducted, in coordination with the permit for fire restoration, an inspector with construction experience as related to fire fighter safety and health may have been able to identify the substandard roof decking material. That information may have led to requiring the materials be up to the current building code requirements. An inspection should also provide an opportunity to relay specific hazards to central dispatch to be associated for that location.

Recommendation #6: Municipalities, building code officials, and authorities having jurisdiction should consider requiring apartment complexes and associated multiple-family dwellings that have been “retrofitted” into current structural building code requirements also be brought up to current codes for such things as sprinkler systems and adequate structural roof members when requests for permits are made.

Discussion: There are many apartment complexes and multi-family dwellings across the country that were built prior to modern day building codes. These codes are in place to specifically protect life and property. During the NIOSH investigation, it was found that the apartment complex where this incident took place had experienced multiple fires requiring structural roof repair. During the application process for building permits is one way for authorities having jurisdiction to identify and require that existing properties are refurbished to meet the current code requirements, with items such as sprinkler requirements and adequate sized roof decking or structural materials.

In this incident, having a sprinkler system possibly could have contained the fire to the room of origin. Adequate structural roofing members could have provided for a safe access to the roof and during vertical ventilation operations.

References

- NFPA [2008]. NFPA 1561: Standard on emergency services incident management system. 2008 ed. Quincy, MA: National Fire Protection Association.

- Dunn V [2000]. Command and control of fires and emergencies. Saddle Brook, NJ: Fire Engineering Book and Videos.

- NFPA [2007]. NFPA 1500: Standard on Fire Department Occupational Safety and Health Program. Quincy, MA: National Fire Protection Association

- IFSTA [2008]. Essentials of fire fighting, 5th ed. Oklahoma State University. Stillwater, OK: Fire Protection Publications, International Fire Service Training Association.

- OSHA [1998]. 29 CFR Parts 1910 and 1926 Respiratory Protection; Final Rule. Federal Register Notice 1218-AA05. Vol. 63, No. 5. January 8, 1998. U.S. Department of Labor, Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Washington DC.

- Clark, B.A. [2005]. 500 Mayday called in rookie school.external icon http://www.firehouse.com/article/10498807/500-maydays-called-in-rookie-school .

- National Incident Management System Consortium [2007]. Incident Command System (ICS)Model Procedures Guide for Incidents Involving Structure Fire Fighting, High-Rise, Multi-Casualty, Highway, and Managing Large-Scale Incidents Using NIMS-ICS. First Edition.Oklahoma State University. Fire Protection Publications.

- International Association of Fire Chiefs [2009]. Rules of Engagement for Firefighter Survival.external icon http://www.iafc.org/operations/legacyarticledetail.cfm?itemnumber=2718. (Link updated 10/4/2012) Date Accessed: July 2011.

- NFPA [1997]. Fire protection handbook. 18th ed. Quincy, MA: National Fire Protection Association.

- NFPA [2010]. NFPA 1710, Standard for the organization and deployment of fire suppression operations, emergency medical operations, and special operations to the public by career fire departments. Quincy, MA: National Fire Protection Association.

Investigator Information

This incident was investigated by Jay Tarley and Stephen T. Miles, Safety and Occupational Health Specialist, and Tim Merinar, Project Officer, with the Fire Fighter Fatality Investigation and Prevention Program, Fatality Investigations Team, Surveillance and Field Investigations Branch, Division of Safety Research, NIOSH in Morgantown, WV. An expert technical review was provided by Gary P. Morris; Fire Chief, Retired. A technical review was also provided by the National Fire Protection Association, Public Fire Protection Division.

Disclaimer

Mention of any company or product does not constitute endorsement by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH). In addition, citations to Web sites external to NIOSH do not constitute NIOSH endorsement of the sponsoring organizations or their programs or products. Furthermore, NIOSH is not responsible for the content of these Web sites.

Additional Information

The Texas State Fire Marshal’s Office conducted a separate investigation of this incident.external icon When completed, their investigation report will be available at http://www.tdi.texas.gov/reports/report6.html

IAFF Fireground Survival Programexternal icon. The purpose of the Fire Ground Survival program is to ensure that training for Mayday prevention and Mayday operations is consistent between all fire fighters, company officers, and chief officers. Fire fighters must be trained to perform potentially life-saving actions if they become lost, disoriented, injured, low on air, or trapped. Funded by the IAFF and assisted by a grant from the U.S. Department of Homeland Security through the Assistance to Firefighters (FIRE Act) grant program, this comprehensive training program applies the lessons learned from fire fighter fatality investigations conducted by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) and has been developed by a committee of subject matter experts from the IAFF, the International Association of Fire Chiefs (IAFC), and NIOSH. http://www.iaff.org/HS/FGS/FGSIndex.htm.

IAFC [2009]. Rules of engagement for structural firefighting, increasing firefighter survivalpdf iconexternal icon. Draft manuscript developed by the Safety, Health and Survival Section, International Association of Fire Chiefs. Fairfax Va. March 2009. http://websites.firecompanies.com/iafcsafety/files/2013/10/Rules_of_Engagement_short_v10_2.12.pdf. (Link Updated 1/14/2014)

The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH), an institute within the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), is the federal agency responsible for conducting research and making recommendations for the prevention of work-related injury and illness. In 1998, Congress appropriated funds to NIOSH to conduct a fire fighter initiative that resulted in the NIOSH “Fire Fighter Fatality Investigation and Prevention Program” which examines line-of-duty-deaths or on duty deaths of fire fighters to assist fire departments, fire fighters, the fire service and others to prevent similar fire fighter deaths in the future. The agency does not enforce compliance with State or Federal occupational safety and health standards and does not determine fault or assign blame. Participation of fire departments and individuals in NIOSH investigations is voluntary. Under its program, NIOSH investigators interview persons with knowledge of the incident who agree to be interviewed and review available records to develop a description of the conditions and circumstances leading to the death(s). Interviewees are not asked to sign sworn statements and interviews are not recorded. The agency’s reports do not name the victim, the fire department or those interviewed. The NIOSH report’s summary of the conditions and circumstances surrounding the fatality is intended to provide context to the agency’s recommendations and is not intended to be definitive for purposes of determining any claim.

call toll free 1-800-CDC-INFO (1-800-232-4636).