Volunteer Fire Fighter Caught in a Rapid Fire Event During Unprotected Search, Dies After Facepiece Lens Melts – Maryland

Death in the Line of Duty…A summary of a NIOSH fire fighter fatality investigation

Death in the Line of Duty…A summary of a NIOSH fire fighter fatality investigation

F2011-02 Date Released: July 3, 2012

Executive Summary

On January 19, 2011, at approximately 1855 hours, a 43-year-old volunteer fire fighter died after being caught in a rapid fire progression. The victim and another fire fighter were conducting a search of a third-floor apartment above the fire, which had started on the first floor. Conditions at the time of entry for the search crew indicated that the fire was under control. The fire had already breached the second-floor apartment through a sliding glass door in the rear of the structure but was oxygen-limited. Another crew was initiating a civilian rescue from the second-floor apartment above the fire when a rapid fire build-up occurred on the second floor. The fire and smoke traveled up the common stairwell, igniting the third-floor apartment and trapping the victim. The victim radioed multiple Mayday calls, but crews were unable to reach him before his facepiece melted from the extensive heat produced by the rapid fire progression. The other fire fighter who was with the victim was searching a bedroom and his exit was cut off by the rapid fire progression. He was forced to bail out a bedroom window and was injured by the fall. Rescue efforts were initiated, the victim was located, and removed from the third-floor apartment. The victim died from exposure to the products of combustion.

Rapid fire event exiting window in common stairwell of apartment building.

(Photo courtesy of fire department.)

Contributing Factors

- Incident Management System

- Personnel Accountability System

- Rapid Intervention Crews

- Conducting a search without a means of egress protected by a hoseline

- Tactical consideration for coordinating advancing hoselines from opposite directions

- Building safety features, e.g., no sprinkler systems, modifications limiting automatic door closing

- Occupant behavior-leaving sliding glass door open

- Ineffective ventilation.

Key Recommendations

- Ensure the first-due arriving officer maintains the role of Incident Commander or transfers “Command” to the next arriving officer

- Ensure that a first-due company officer establishes command, maintains the role of director of fireground operations, does not become involved in fire-fighting operations, and ensures incident command is effectively transferred

- Fire departments should ensure that a separate Incident Safety Officer, independent from the Incident Commander, is appointed at each structure fire

- Ensure fire fighters are trained in the procedures of searching above the fire and are protected by a hoseline

- Ensure that interior search crews’ means of egress are protected by a staffed hoseline

- Ensure that a rapid intervention team or crew is established and available to immediately respond to emergency rescue incidents.

Introduction

On January 19, 2011, at approximately 1855 hours, a 43-year-old volunteer fire fighter died after being caught in a rapid fire progression. On January 20, 2011, the U.S. Fire Administration notified the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health of this incident. On January 31, 2011 two safety and occupational health specialists and the project officer from the NIOSH Fire Fighter Fatality Investigation and Prevention Program traveled to meet with the fire department’s investigation committee and inspect the incident scene. At the request of the fire department to return after their internal investigation, two safety and occupational health specialists, an investigator, and the project officer from the NIOSH Fire Fighter Fatality Investigation and Prevention Program returned to investigate this incident. On March 5–9, 2011, meetings were conducted with fire department members and representatives of the Office of the State Fire Marshal and the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms. Interviews were conducted with fire fighters, fire officers, and law enforcement and dispatch personnel who were involved with this incident. The investigators reviewed witness statements, dispatch logs, and the death certificate. The incident site was visited and photographed.

Fire Department

This combination department consists of 1,050 career members and approximately 2,000 volunteers. The department operates out of 25 career stations and 33 exclusively volunteer stations within the county. The volunteer companies function as independent fire departments, which operate under the county deployment plan. The stations serve a population of more than 800,000 people in a geographic area of approximately 612 square miles of land and 28 square miles of waterways.

Career Fire Companies

The county operates 25 career fire stations under three battalions, which includes 28 engine companies, 7 truck companies, 28 advanced life support (ALS) medic units, and 23 brush units. The department also operates a hazardous materials response and support unit, a decontamination unit, and an advanced tactical rescue (ATR) team specially trained for unusually difficult, complex rescues, such as building collapses, water rescues, trench rescues, high-rise rescues, and other special operations procedures.

The career department has 1,050 uniformed personnel who staff administrative offices, an operations division, a fire training academy, a fire marshal’s office, and a fire investigations unit. The Operations Division shift schedule consists of a 10-hour shift and a 14-hour shift each day. Four shifts work two 10-hour shifts (0700–1700), two 14-hour shifts (1700–0700), and are off for four days. “A” Shift and “C” Shift operate in Battalions 1, 2, and 3. “B” Shift and “D” Shift operate in Battalions 11, 22, and 33.

Volunteer Fire Companies

The county has 33 independently operated volunteer fire companies which include 61 engine companies, 6 truck companies, 17 ALS medic units, 6 tenders (tankers), 9 heavy rescue (squad) units, plus brush and support units. More than 2,000 citizens volunteer in the fire service as active responders, fundraisers, and support personnel. Though volunteer companies are independent, private corporations, the county operates a joint fire service with dedicated career and volunteer responders working together at emergency scenes.

The volunteer fire company where the victim was a member was formed in 1909 and has approximately 100 members. The department protects and serves 30,000 people in a geographic area of more than 45 square miles. The department operates three engine companies, one heavy rescue (squad), and one utility vehicle.

Staffing and Response

The minimum staffing on each engine and truck for the career department is four fire fighters, including an officer. If the officer is on leave or detailed to another position or function, another officer (Captain or Lieutenant) is assigned to fill the vacancy. The department does not utilize fire fighters as Acting Officers on the company level. The battalion chief responds alone without the benefit of a chief’s aide or staff assistant. The division chief and safety officer are not dispatched to an incident until the second alarm. All of the department officers are trained and capable of filling the safety officer position if assigned.

The first alarm assignment for an apartment fire is:

- 4 engines (Fourth due engine is designated as RIT)

- 2 trucks

- 1 battalion chief

On the notification of a “working fire,” a RIT Task Force is dispatched, which consists of 1 engine, 1 truck, and 1 ALS medic unit.

Training and Experience

The state of Maryland requires training for volunteer fire fighters that consists of NFPA 1001, Standard on Fire Fighter Professional Qualifications, Fire Fighter I, Hazardous Materials Awareness, Hazardous Materials Operations, and First Responder. The process requires annual recertification.

The career fire department involved in this incident has a recruit school, which is 18 weeks in length and consists of NFPA 1001, Standard on Fire Fighter Professional Qualifications, Fire Fighter I, Fire Fighter II, Hazardous Materials Awareness, Hazardous Materials Operations, and First Responder.

In the state of Maryland training hours are as follows:

Firefighter I is 108 hours

Firefighter II is 60 hours

First Responder is 45 hours

Hazardous Materials Operations is 24 hours

Hazardous Materials Awareness is 12 hours.

In the combination county fire department, a volunteer fire fighter may work in an immediately- dangerous-to-life and-health (IDLH) environment if they meet the following requirements:

Fire Fighter I

Hazardous Materials Operations

CPR

Bloodborne Pathogens certification

Completed medical surveillance

SCBA fit test

For officers, the training requirements are as follows:

- Lieutenant: NFPA 1021, Standard for Fire Officer Professional Qualifications, Fire Officer I

Captain: NFPA 1021, Standard for Fire Officer Professional Qualifications, Fire Officer II Fire Officer II

Battalion Chief: NFPA 1021, Standard for Fire Officer Professional Qualifications, Fire Officer III Fire Officer III

Division Chief and above: NFPA 1021, Standard for Fire Officer Professional Qualifications, Fire Officer IV Fire Officer IV

Victim

The victim had previously been a career firefighter/paramedic with more than 16 years of experience and had received training on topics that include: NFPA 1001, Standard on Fire Fighter Professional Qualifications Firefighter I and Firefighter II; NFPA 1031, Professional Qualifications for Fire Inspector, Inspector I; NFPA 1033, Standard on Professional Qualifications for Fire Investigator, Fire Investigator ; NFPA 1041, Professional Qualifications for Fire Service Instructor, Fire Instructor III; NFPA 1021, Standard on Fire Officer Professional Qualifications, Fire Officer II; EMT-Paramedic; Rescue Swiftwater, Rescue, Trench, Confined Space, and High Angle Rescue Technician. He also served as an instructor at a federal fire-rescue academy and was an instructor for the department’s flashover simulator.

Initial Incident Commander

The captain who was the initial incident commander had more than 21 years of experience and received training on topics such as: NFPA 1001, Standard on Fire Fighter Professional Qualifications, Fire Fighter III; NFPA 1002, Standard on Professional Qualifications for Driver/Operator; NFPA 1031, Standard on Professional Qualifications for Fire Inspector, Fire Inspector I; NFPA 1033, Standard on Professional Qualifications, Fire Investigator I; NFPA 1041, Professional Qualifications for Fire Service Instructor, Fire Instructor II; and NFPA 1021, Standard on Professional Qualifications for Fire Officer, Fire Officer III.

Incident Commander

The Battalion Chief had more than 30 years of experience and had completed training on topics such as: NFPA 1001, Standard on Fire Fighter Professional Qualifications, Fire Fighter III; NFPA 1041, Professional Qualifications for Fire Service Instructor, Fire Instructor III; NFPA 1021, Standard on Professional Qualifications for Fire Officer, Fire Officer; and Hazardous Materials Operations.

Personnel Accountability System

Each member of both the career and volunteer departments are assigned two personnel accountability tags. Each tag consists of a picture, an identification number, and a barcode. One tag is given to the officer at the beginning of the shift (career personnel) or when the apparatus is responding (volunteer personnel) to an incident. One tag stays on the apparatus and would go to “Command” or a “division/group supervisor.” The tags are white for fire operations and blue for EMS personnel.

Personal Protective Equipment

At the time of the incident, each fire fighter entering the structure was wearing their full ensemble of personal protective clothing and equipment, consisting of turnout coats and pants, Nomex® hood, helmet, gloves, boots, and a self-contained breathing apparatus (SCBA).

Each fire fighter’s SCBA contained an integrated personal alert safety system (PASS) device. This combination department issues portable hand-held radios to all fire fighters by assigning radios to each apparatus riding position.

The victim’s SCBA was submitted to the National Personal Protective Technology Laboratory (NPPTL) NIOSH for evaluation. The SCBA was delivered to NPPTL on March 8, 2011, and inspected on April 12, 2011. The unit was identified as a 4500-psig SCBA (NIOSH approval number TC-13F-212, 45-minute duration unit). The SCBA suffered extensive damage from heat and fire and was covered with dirt, grime, foreign particulate material, and soot. The SCBA facepiece lens was melted with a hole penetrating the lens material (see Photo 1). The cylinder valve, as received, was damaged; the hand wheel was operable. All gauges were unreadable and heavily damaged. The regulator and facepiece were heavily damaged and unusable, and the regulator plastic materials had been melted and were bonded onto the facepiece. The SCBA air cylinder was heavily damaged and burned. The outside cylinder covering was black, and the labeling was unreadable. The air cylinder was so heavily damaged that the name of the manufacturer, date of manufacture, DOT number, and re-test date label were unreadable. Because of this, a cylinder re-test date could not be determined. In light of the condition of the SCBA obtained during this investigation, NIOSH was not able to test and returned the unit to the fire department. The full SCBA evaluation report is available from NIOSH upon request.

Photo 1. Victim’s melted facepiece lens.

(NIOSH photo.)

Weather

At the time of the incident, the temperature was approximately 45 degrees F. The winds were out of the northwest east at approximately 5 mph with gusts up to 17 mph.

Structure

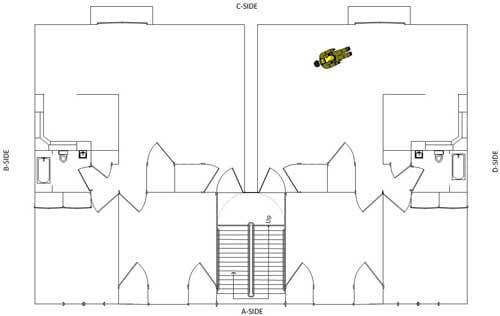

The apartment building involved in this incident consisted of two apartments on each of the three floors, separated by a common stairwell enclosed in the center. The apartments located on the left-hand side of the stairwell were designated as 1A, 2A, 3A. The apartments located on the right-hand side of the stairwell were designated as 1B, 2B, 3B. The building was built in the 1950s, and the code at that time did not require automatic sprinklers. The building was ordinary, Type III construction with exterior masonry walls, wooden interior walls covered with sheet rock, wooden floor joists, and lightweight roof trusses covered with plywood and asphalt shingles. All six apartments had a common layout ranging from 950 to 1,020 square ft. The bottom floor, which was the fire floor, had ground-level windows at the front and a walkout sliding glass door at the back (see Diagram).

Fire Behavior

A first floor occupant called the 911 center and informed them of a fire that originated in the kitchen of their ground-floor apartment. When the fire department arrived, the fire was blowing out of the open sliding glass door of the ground floor apartment and was extending to the wooden balcony on the second floor (Photo 2). Fire and smoke also traveled up the common stairway and later exited through the open front door (Photo 3).

The fire was not contained by companies on Side C, compromised the second-floor sliding glass door, and spread to an overstuffed piece of furniture just inside the doorway of the second floor. This fire remained in a smoldering stage, consuming all the available oxygen, until the front door was opened. During the rescue of two occupants in the second floor apartment above the fire apartment, oxygen and sufficient cross ventilation were introduced to allow the smoldering fire to reach flashover, and the fire entered the common stairway and the third-floor apartment trapping the victim. Note: The fire traveled from the second floor to third floor apartment due to interference of the automatic door closures. Each apartment entrance door was equipped with an automatic self-closing device. Due to new carpet recently installed in each apartment, the doors did not automatically close. The door height had not been adjusted to allow the doors to self-close.

Note: The Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF) has developed a computerized fire model to aid in reconstructing the events of the fire. This model is available at the ATF Web sitepdf iconexternal icon at: http://www.baltimorecountymd.gov/sebin/a/m/b_atffireanalysis120319.pdf .

Photo 2. Orientation of Side C.

Second and third floor balconies are on the left.

(Photo courtesy of fire department.)

Photo 3. Smoke exiting up stairwell through open door.

(Photo courtesy of fire department.)

Apparatus

First Alarm 1818 hours

Engine 11 (E11) with a captain, lieutenant, driver/operator, fire fighter

Engine 10 (E10) with an officer, driver/operator, and two fire fighters

Engine 1 (E1) with an officer, driver/operator, and two fire fighters

Truck 1 (T1) with an officer, driver/operator, and two fire fighters

Truck 8 (T8) with an officer, driver/operator, tiller operator, fire fighter

Engine 292 (E292) with an officer, driver/operator, and fire fighter

Battalion Chief 11 (BC11) battalion chief

Division Chief 3(DC3) with a division chief, and a captain acting from E15 (E15C) for training

Dispatched at 1821 hours

Squad 303 (SQ303) with an officer (victim), driver/operator, and three fire fighters

Engine 307 (E307) with an officer, driver/operator, and two fire fighters

Dispatched at 1821 hours

Engine 301 (E301) with an officer, driver/operator, and two fire fighters

Investigation

On January 19, 2011, at approximately 1818 hours, the 911 center received a call of a kitchen fire that was spreading. A first-alarm assignment was dispatched. Engine 11 (E11) was the first apparatus to arrive on the scene, at 1820 hours, and reported a working fire which quickly evolved into a rescue of an occupant from a third floor apartment. The Captain from E11 assumed “Command” of the incident and ordered his crew to advance a handline to the front door to search for and extinguish the fire. From outside the front of the structure, the smoke conditions seemed typical of a kitchen fire. Note: During the interviews, the Captain from E11 noted that he had based his size-up from his experience with previous kitchen fires he had responded to in this apartment complex. The crew was at the front door preparing to make entry when a civilian woman appeared at a third-floor window (Apartment 3A) frantically calling for help, and threatening to jump (see Diagram). The E11 captain called for Limited Command in order to assist with the rescue. Note: The fire department uses the term “Limited Command” which is comparable to “Fast Attack Mode – Mobile Command”.

The captain and driver immediately grabbed a ground ladder in order to rescue the woman. The rest of the crew opened the front door, which led to a common stairwell, to possibly assist with the rescue. The intense heat in the stairwell immediately drove them to the ground and they closed the door.

When they reached the ground with the woman, she was hysterical. The E11 captain had to physically escort the woman to police, approximately 200 yards away.

The driver/operator charged the handline and the crew attempted to make entry to locate and extinguish the fire. When they opened the front door to the common stairwell, thick, black, pressurized smoke poured from the doorway (see Photo 4). Engine 10 (E10) arrived on scene at 1823 hours and supplied water to E11 with a 4-inch supply line. “Command” escorted the hysterical civilian away from the incident. “Command” told the E10 officer to pull a second handline off E11 to back up the crew making entry. “Command” returned from escorting the civilian and told the E10 officer that he was going to Side C to complete his size-up. The E10 officer was assigned as Division A.

Engine 1 (E1) arrived on the scene at 1825 hours as the third-due engine and was directed to Side C of the structure. The E1 officer ordered his driver to pick up E10’s supply line and pump to E11. The E1 crew took forcible entry tools and a ground ladder to Side C.

Photo 4. Ladder to window where civilian woman was rescued upon arrival. This is Side-A; the building designation of the apartment was 3A.

(Photo courtesy of fire department.)

During this time on Side A of the structure, Truck 1 (T1) arrived on the scene at 1825 hours as the third-due apparatus and noticed E11 at the front door with heavy, black smoke rolling out of the door. The rescue from the third floor had already taken place. The crew from T1 decided their tactical assignment was to focus on ventilation, entry, and search. The E11 lieutenant and E11 fire fighter opened the front door to advance a charged handline down and into the fire floor, which was down a flight of stairs from the front door of the apartment building. Once the door was opened, smoke and fire erupted from the hallway door. The E11 lieutenant requested E10 to vent the bottom floor windows. The E10 officer took out the two right front windows of Apartment 1B, which was the fire apartment, from left to right. Fire was exiting the top of the doorway of the fire apartment. The E10 captain was feeding line to E11 as they attempted to knock down the fire and make entry in the fire apartment. The intense fire, heat, and smoke did not allow them to advance the handline down the steps, and smoke was pouring into the stairwell. They requested the E10 crew to operate the handline through the left window of the fire apartment in an attempt to cool the fire.

The E11 captain proceeded to walk around to Side C of the structure. This required him to walk around two additional apartments (Exposure B1 and Exposure B2) of the fire building. When he arrived at Side C of the structure, he encountered a free-burning fire in the entire fire apartment (Apartment 1B). The sliding glass door that led to this apartment was completely gone, and fire was starting to extend to the wooden balcony of the second-floor apartment (Apartment 2B), directly above the fire apartment. The E11 captain called for crews to report to Side C of the structure. Truck 8 (T8) and Engine 292 (E292) arrived on the scene at approximately 1830 hours and positioned at the alley behind Side C of the structure. Note: E292 was the fourth-due engine, which according to departmental procedures was to act as the rapid intervention team (RIT). This function was not assigned until later in the incident. Also, the alley was approximately 75 feet from the structure. E1 placed their extension ladder to Apartment 3A on Side C to conduct a search for occupants. They encountered moderate smoke, requiring them to don their SCBA, but they could see standing up. They opened the door to the hallway and observed heavy smoke, heat, and steam. They closed the door and exited back down the ladder. “Command” told T8 that Apartment 2A had not been searched and assigned the E292 officer as Division “C” and announced it over the radio. The assignment to Division “C” was for E292 to operate the hoseline from outside of the structure, to contain the fire in Apartment 2B, and to not push the fire on the attack crew entering from Side A. E1 then moved their ladder over to the right side of the Apartment 3B balcony, above the fire.

At 1831 hours, Squad 303 (SQ303) arrived on the scene and reported to the front of the building. Two handlines were being operated at Side A at this time. One line was operated by E11, down the steps, and the other one was operated by E10, flowing water inside the ground-level window just to the right of the front door. One SQ303 fire fighter assisted in knocking out more of the remaining windows for E10 and prepared to make entry. SQ303’s officer (the victim) instructed his remaining two fire fighters that they were going to conduct a search from the top floor down. They were just prepared to make entry when one of them was asked to back up E11.

E11 made entry again with the E10 officer as third on the line. The SQ303 fire fighter remained at the doorway, flaking hose. E11 made it to the door of the fire apartment, and then an E11 fire fighter had to exit due to his low-air alarm sounding. The SQ303 fire fighter replaced the E11 fire fighter as second on the handline. They made entry into the fire apartment and could hear another crew operating a handline inside the fire apartment.

Engine 307 (E307) arrived during this time, completed securing a second water source, and the crew proceeded to the rear of the structure for instructions from the Division “C”. The E307 officer looked for the E292 officer (Division “C”) but could not find him. Note: E292 crew was operating a handline inside the fire apartment from Side C at this time. The conditions at the rear were moderate grey smoke. The E307 officer noticed that both the first-floor and second-floor sliding glass doors were broken out from the fire. He placed a 14-foot ground ladder through the second-floor wood balcony of Apartment 2B, which had also been consumed by the fire.

On Side C, T8 had just placed a ladder to the corner of Apartment 2A to conduct a search. E292 was inside the fire apartment, conducting suppression operations. T8 broke the sliding glass doors on Apartment 2A and encountered light, white smoke conditions. They went on air and conducted a quick search of the apartment and exited the apartment through the open front door in the common stairwell. They encountered grayish white smoke, with poor visibility, in the stairwell. Engine 8 (E8) arrived on the scene at 1835 hours and noticed the handline inside the fire room and asked where the E292 officer (Division “C”) was located to receive orders.

The victim and one fire fighter proceeded up the stairs to Apartment 2A. They forced the door with very little smoke. They conducted a quick search and returned to the hallway. The victim told the fire fighter they were going to the third floor to conduct a search. Note: The victim and his fire fighter did not receive an assignment from “Command” to search. They reported to “Command” at 1838 hours via radio that they were searching the third floor. Smoke conditions on the third floor were worse than the second floor. They had to feel around to find the door. They forced the door to Apartment 3A, and encountered very little smoke inside the apartment as they conducted their search. They walked to the front bedroom where the civilian had been rescued from the window and then proceeded to the rear balcony. They could see fire at the rear of Apartment 1B, which was on the opposite side of the stairwell from their location.

The victim and fire fighter exited Apartment 3A, re-entering the hallway where the smoke conditions had improved. They forced the door of Apartment 3B and encountered moderate smoke and minimal heat conditions. They were walking upright with the smoke banked down a couple feet from the ceiling. They became separated when the fire fighter entered a bedroom to quickly search for a civilian. The victim went toward the Side C of the structure towards the living room/dining room area, while the fire fighter entered a bedroom on Side A for a quick search.

During this time, T1 had laddered Apartment 2B and took out the left bedroom window of the two located on Side A. Gray-colored smoke was coming out of the window. The driver/operator from T1 laddered the right bedroom window and reported Apartment 2B was clear of smoke. T1 entered Apartment 2B through the right bedroom window on Side A (window closest to Side D) and proceeded through the apartment to Side C where they encountered reduced visibility and minimal heat. Note: It is believed that the fire at this time had compromised the rear sliding door and had started to burn the living room furniture but was in the smoldering stage due to the lack of oxygen. T1 immediately found a civilian victim on a couch in the living room at approximately 1836 hours and began to remove the victim though the Side “A” bedroom window. Note: Conditions had rapidly deteriorated in the approximately 30 second time frame it took to find and begin to remove the civilian. T1, attempting to remove the civilian victim, entered the wrong bedroom from where they had just entered due to the limited visibility from the products of combustion from the rapidly growing fire consuming the living room furniture. They closed the door to the bedroom and passed the civilian to a ladder crew. Within an estimated 90 seconds, they reopened the bedroom door. The hallway area was completely engulfed in fire.

Just as T1 was taking the civilian into the bedroom for rescue, T8 had forced the door to Apartment 2B. Note: It is believed that the apartments in this section had new carpeting that would not allow the automatic door-closing feature to work properly. They entered standing upright, with poor visibility. A T8 fire fighter made it to the sliding glass doors facing Side C of the structure and removed what glass remained. The deck appeared to be burnt through by fire from the lower apartment, and a couch (with a portion of the armrest in the sliding glass doorway) had been on fire and still maintained small, visible flames. The T8 officer, who was several feet behind the fire, could hear his fire fighter removing the remaining glass but could not see him or the sliding glass doors.

At this time, T8 had been in Apartment 2B approximately 40 seconds. The officer from T8 turned around toward the front door where they had just walked from, and the visibility conditions greatly improved. He immediately saw a female civilian slumped over in a chair and called to his fire fighter for assistance. At 1840 hours, the T8 officer transmitted an “Urgent” message for a civilian rescue from the second floor. Immediately thereafter, they were attempting to remove the civilian from the chair as the fire and smoke quickly intensified and was rolling over their heads, out the front door and into the common stairwell. They were forced to flee down the stairs with the civilian. The T8 fire fighter was the last one out and was shielding the civilian from the intense smoke, heat, and flames. His turnout gear and helmet were badly damaged by fire while exiting the apartment down the stairs.

The T1 driver and E10 officer took the ladder used in the third-floor rescue and moved it to the right side of Side A. The stairway started to flash over as they moved the ladder from the window closest to the A/B corner to the window closest to the A/D corner of the third floor (see Diagram). The T1 driver placed another ground ladder to a window over the stairwell and operated a 1¾-inch handline through the window. He saw the second civilian being brought down the stairwell in heavy fire conditions.

Two fire fighters from E301 assisted with the removal of the second civilian and noted the fire rolling above them in the stairwell. They then advanced the initial attack hoseline up the stairs, between the second and third floors, with high-heat conditions. Note: The E301 crew stated that the hallway was crowded with fire fighters at the third floor. One fire fighter manned the nozzle on the stairs while the other one went back down and got the other handline that was used through the front window during the initial attack. He advanced the handline to Apartment 2B and fought heavy fire that was exiting the doorway.

At the same time on the third floor, the SQ303 fire fighter (in Apartment 3B) saw something on the bed that turned out to be clothes and then heard something behind him. He turned and saw that fire had filled the hallway and cut off his exit. He immediately went around the bed to find or locate the window. Conditions quickly deteriorated due to high-heat conditions and zero visibility. “Command” sounded the evacuation horns at 1841 hours and within 10 seconds received an emergency call from the SQ303 officer. Note: “Command” of the incident had been transferred from the Captain of E11 to Battalion 11 (BC11). The department sounded the evacuation tones while he conducted a left-hand search for the window. He found the window, knocked it out, and shined his flashlight out to signal for help. He readied himself at the window and waited for a ground ladder as fire advanced into the bedroom.

Photo 5. SQ303 fire fighter bailing out of a third-floor window.

(Photo courtesy of fire department.)

Once a ground ladder was placed at the window, the SQ303 fire fighter bailed out of the third-floor window, head-first, at 1842 hours (see Photo 5). A fire fighter from E301 was aware of the circumstances and was able to partially catch the SQ303 fire fighter to break his fall and help reduce the severity of injury. The E301 driver assisted the fire fighter after he bailed out of the window. The SQ303 driver asked where the victim was and learned that the victim was still inside. The SQ303 driver grabbed the E301 crew and made re-entry. They saw the T1 driver operating a handline through the window and took it from him and advanced it to the third-floor landing. During this time, the victim was attempting to give his LUNAR (location, unit number, assignment, resources needed) and called for a Mayday at 1847 hours. Note: The victim mistakenly gave his position as the third-floor alpha/bravo corner, which is why they searched Apartment 3A.

A captain from Engine 15 (E15C), who was training for Division Chief, was riding with Division Chief 3 and was directed to go inside and do a reconnaissance of the interior. The crew operating the handline at the third-floor landing had the fire knocked down enough so that E15C could enter and make a quick search of Apartment 3A. The SQ303 driver ran out of air, and the other E301 fire fighter went back down the stairs, leaving the one E301 fire fighter on the handline. He attempted to knock the fire back in Apartment 3B so that E15C could make entry. The fire was rolling out the door. The captain could only make it about 5 feet inside the door due to the heavy fire. E15C came back out, and the fire fighter shut down the nozzle. E15C and the E301 fire fighter heard a PASS device sounding. The captain re-entered Apartment 3B while the E301 fire fighter flowed water at the ceiling to keep the fire off him. The E15C did a left-hand search and found the victim by spotting his boots.

During this time on Side C of the structure, the E8 officer was on E1’s ladder. The E8 officer had just finished fighting the fire on the second floor after watching T8 conduct their search. The E8 officer heard the Mayday and went up the ladder with a handline to the third floor. He was sweeping the ceiling as thick, black smoke rolled out from the top area of the sliding glass doorway. A fire fighter from E1 was backing the E8 officer up on the ladder. The E8 officer caught a glimpse of the side of the victim crawling on his hands and knees (see Diagram). He yelled and beat the nozzle on the ladder and balcony railing in an attempt to lead the victim to the doorway. The victim disappeared into the smoke. The E8 officer dropped the nozzle and jumped onto the balcony. He found the victim approximately 6 feet inside and to the right of the doorway. He was conscious and breathing as the E8 officer attempted to drag the victim to the doorway. Note: The hole in the victim’s facepiece is consistent with facepieces that have been compromised by fire under the positive pressure of a breathing apparatus. The E8 officer got the victim turned around and to the threshold when the victim became limp and was caught on something. The E8 officer was unable to move the victim alone.

At this time, E15C met the E8 officer who was out of air, and they both attempted to remove the victim. The E307 officer assisted them as they drug the victim outside onto the balcony, but they were unsuccessful in removing the victim from the balcony. Additional crews and an aerial ladder were needed to remove the victim from the structurally unstable balcony. The victim was placed in a Stokes Basket and was lowered to the ground and then loaded in an awaiting ambulance and transported to a local hospital where he was pronounced dead.

Diagram. Typical apartment layout.

Contributing Factors

Occupational injuries and fatalities are often the result of one or more contributing factors or key events in a larger sequence of events that ultimately result in the injury or fatality. NIOSH investigators identified the following items as key contributing factors in this incident that led to the fatality:

- Incident Management System

- Personnel Accountability System

- Rapid Intervention Crews

- Conducting a search without a means of egress protected by a hoseline

- Tactical consideration for coordinating advancing hoselines from opposite directions

- Building safety features

- Occupant behavior-leaving sliding glass door open

- Ineffective ventilation.

Cause of Death

The death certificate listed the cause of death as thermal burns to the airway.

Recommendations

Recommendation #1: Ensure the first-due arriving officer considers establishing a Command Post or transfers “Command” to the next arriving officer based upon the needs of the incident.

Discussion: Effective incident management is essential for the successful outcome of any emergency incident. The individual assuming the role of Incident Commander must follow these essential steps:

- The first arriving officer that has responsibility for the incident assumes command of the incident;

- The Incident Commander should conduct an initial and on-going situational assessment of the incident;

- The Incident Commander should establish an effective communications plan;

- The Incident Commander should develop the incident objectives from the situational assessment and form appropriate strategy and tactics, i.e., Incident Action Plan (IAP);

- The Incident Commander should deploy available resources and request additional resources based upon the needs of the incident;

- The Incident Commander should develop an incident organization for the management of the incident;

- The Incident Commander should review, evaluate, and revise the strategy and tactics based upon the needs of the incident;

- The Incident Commander should provide for the continuity, transfer, or termination of command.

As Command is transferred, so is the responsibility for these functions. The first six (6) functions should be addressed immediately from the initial assumption of Command.

In this situation, the officer of E11 (“Command”) was faced with an immediate rescue of a civilian plus initiating a fire attack to control the fire. The officer opted to initiate “Limited Command” which is similar or comparable to “Fast Attack Mode – Mobile Command”. The officer arrives and assumes command of the incident. Their direct participation in the attack will make a positive difference in the outcome (search and rescue, fire control, and crew safety). They give an initial radio report and quickly assign companies coming in behind them. The next arriving units will stage until given an assignment. The Incident Commander goes inside (when in the offensive mode) with a portable radio supervising their crew in the attack.

In the “Fast Attack Mode”, the Incident Commander should initiate and continue command until a command officer arrives and the transfer of command is completed. The entire team responding in behind the fast attack crew must realize that the Incident Commander is in an attack position inside the hazard zone attempting to quickly solve the incident problem.

The “Fast Attack Mode – Mobile Command” has a finite life and should not last more than a couple of minutes and will end with one of the following:

- Situation is stabilized;

- Command is passed or transferred from the fast attack company officer (Incident Commander) to a subsequent arriving company officer or arriving command officer;

- If the situation is not stabilized, the fast attack company officer (Incident Commander) must move to an exterior (stationary) command position and is now in the Command mode.

Another factor to consider when the “Fast Attack Mode” continues for an extended period of time is that the Incident Commander becomes overloaded with information (task saturation or task overload).1 With all the various tasks being performed on Side A and Side C, it is very difficult to address issues dealing with situation evaluation, deployment management, strategy, the incident action plan, communications, personnel accountability, fire fighter and responder safety, rapid intervention crews (RIC), and other essential job tasks that are the responsibility of the Incident Commander.

At this incident, the officer from E11 assumed “Command” at 1821 hours and “Command” was then transferred at 1839 hours to Battalion 11 (BC11). This incident operated for 18 minutes without formal command being established to develop incident objectives, situational assessment, strategy and tactics, or accountability. This shows the importance of transferring command to another company officer or command officer that has the ability to utilize a tactical worksheet and a personnel accountability board. Also a command post has the necessary communications to utilize the dispatch channel and fireground tactical channel(s).

According to NFPA 1561 Standard on Emergency Services Incident Management System, §5.3.1, “the incident commander shall have overall authority for management of the incident.”2 In addition to conducting an initial size-up, the incident commander must establish and maintain a command post outside the structure to assign companies, delegate functions, and continually evaluate the risk versus gain of continued fire-fighting efforts. In establishing a command post, the IC shall ensure the following (NFPA 1561, §5.3.7.2):

- The command post is located in or tied to a vehicle to establish presence and visibility.

- The command post includes radio capability to monitor and communicate with assigned tactical operations, command, and designated emergency traffic channels for that incident.

- The location of the command post is communicated to the communications center.

- The incident commander, or their designee, is present at the command post.

- The command post should be located in the incident cold zone.2

The use of a tactical worksheet can assist the IC in keeping track of various task assignments on the fireground. It can be used along with preplan information and other relevant data to integrate information management, fire evaluation, and decision making. The tactical worksheet should record unit status and benchmark times and include a diagram of the fireground, occupancy information, activities checklist(s), and other relevant information. The tactical worksheet can also aid the IC in continually conducting a situation evaluation and maintaining personnel accountability.3

Recommendation #2: Fire departments should consider providing battalion chiefs with a staff assistant or chief’s aide to help manage information and communication.

Discussion: A chief’s aide, staff assistant, or field incident technician are positions designed to assist an IC with various operational duties during emergency incidents. The chief’s aide is an essential element for effective incident management. At an emergency incident, the staff assistant can assist with key functions, such as managing the tactical worksheet; maintaining personnel accountability of all members operating at the incident (resource status and deployment location); monitoring radio communications on the dispatch, command, and fireground channels; control information flow by computer, fax, or telephone; and access reference material and pre-incident plans.

The personnel accountability system is a vital component of the fire fighter safety process. Accountability on the fireground can be maintained by several methods: a system using individual tags assigned to each fire fighter, a riding list provided by the company officer, a SCBA tag system, or an incident command board.2, 4-5 The system is designed to account and track personnel as they perform their fireground tasks. In the event of an emergency or Mayday, the personnel accountability system must be able to provide a rapid accounting of all responders at the incident. This is an essential responsibility of the chief’s aide. Chief officers are required to respond quickly to emergency incidents. In their response, they have to be fully aware of heavy traffic conditions, construction detours, traffic signals, and other conditions. More importantly, the chief officer must also monitor and comprehend radio traffic to assess which companies are responding, develop a strategy for the incident based upon input from first-arriving officers, and develop and communicate an incident action plan that defines the strategy of the incident. A chief’s aide can assist the battalion chief or chief officer in processing information without distraction and complete the necessary tasks en route to the scene.

Departments should consider the chief’s aide to be an individual who has the experience and authority to conduct the required tasks. Other potential roles for the chief’s aide include assisting with the initial size-up, completing a 360-degree size-up, coordinating progress reports from sector/division officers, and many others. The aide position can be used as a training position to help facilitate officer development. There also are non-emergency functions for the chief’s aide that are vital to the daily operations of the department. Some jurisdictions assign a chief’s aide to command officers to perform daily administration functions (such as position staffing and leave management).

In this incident, an aide could have set up the command post and accountability system for the numerous career and volunteer companies responding. This would have allowed the IC to develop an Incident Action Plan and make tactical decisions regarding crew accountability and protection.

Recommendation #3: Fire departments should increase staffing during the use of an Incident Command Team to ensure command and fire fighter safety during emergency operations.

An Incident Command Team or Incident Advisory Team is a group of command officers, located at the strategic level of the Incident Command System, who have specific roles and responsibilities, especially during the initial stages of an incident. Front loading the incident with the Incident Command Team is essential especially during the first hour of the incident, which is most often when fire fighters are seriously injured or killed.

Since the inception of the Incident Command System, the duties and responsibilities of the Incident Commander have significantly increased. As an incident escalates, it is difficult for one individual to effectively manage a complex emergency operation. The Incident Commander must address issues dealing with situation evaluation, deployment management, strategy, the incident action plan, communications, personnel accountability, fire fighter and responder safety, the tactical worksheet, rapid intervention crews (RIC), and other essential job tasks. According to Chief Alan Brunacini, to ask one person to command and control a complex incident is unfair to this individual, the fire fighters, and the citizens we protect.1

An Incident Command Team is a group of three individuals—the Incident Commander, the Support Officer, and a Senior Advisor—who manage any emergency incident. The advantages of an Incident Command Team are significant:

- Effective method for managing Type 5(initial attack, single-resource, low complexity) and Type 4 (initial attack, multiple resources, low to moderate complexity) incidents.

- Effective command structure.

- Fewer times “command” is transferred.

- Three officers are better than one officer.

- Incrementally built.

- Smooth transition from a small incident to a large incident.

Most importantly,

- Strong command presence during the crucial first hour of an incident.2

Prior to this incident, no agreements had been established.

The Incident Commander is typically the first command officer to arrive, such as a battalion chief, who assumes “Command” of the incident and is positioned in a strategic position. The incident commander has the resources to support the needs of communications, personnel accountability, and a tactical worksheet. If the initial Incident Commander is arriving on the first-due engine company, the officer assumes command in a “fast attack mode” and operates with the crew on the interior until the first command officer arrives on scene. At this time, command can be transferred to the command officer who has the resources (command vehicle/command van) to effectively manage the incident. The Incident Commander must be in an environment away from distractions and interruptions.

The Support Officer is a senior command officer with years of fire-fighting and command experience. One of the first tasks of the support officer is to ask the Incident Commander for the incident action plan (IAP). If the IAP has not been developed, it must be immediately developed and communicated. If the IAP has been developed, the Support Officer has the responsibility to agree with the IAP or modify it. Additionally, the Support Officer provides direction relating to tactical priorities, evaluates the need for additional resources, assigns logistical and safety responsibilities, controls the tactical worksheet, evaluates the tactical-level and task-level organization and management, and protects the Incident Commander from distractions and interruptions.

The Senior Advisor is the third component of the Incident Command Team and is usually a ranking fire officer, such as a division chief, assistant chief, or fire chief. The Senior Advisor is responsible for reviewing and evaluating the IAP, providing “the big picture” experience, reviewing the tactical level management, developing a strategic organization, serving as a liaison with other agencies and elected officials, but remaining uninvolved with the tactics.

The Incident Command Team concept provides a significant advantage for command and control of multiple-alarm incidents. The support positions are staffed during a critical time in the incident (usually 10–40 minutes into an incident) when the Incident Commander is most challenged. The front-loaded Incident Command System is effective for ensuring the safety of fire fighters.

In this incident, the Incident Command Team would have front-loaded the incident with a command structure during a critical time of the incident when multiple company operations are occurring on Side A and Side C of the building plus all three floors of the apartment building. One of the true benefits of this concept is to ensure that the Incident Commander does not reach the point of task saturation. The Incident Commander can quickly be overwhelmed at an incident which is very dynamic, such as this one. By utilizing the Incident Command Team, this process allows essential incident management functions to occur early in an incident to ensure for a successful outcome of an incident.

Recommendation #4: Fire departments should ensure that a separate Incident Safety Officer, independent from the Incident Commander, is appointed at each structure fire.

Discussion: According to NFPA 1561 Standard on Emergency Services Incident Management System, 2008 Edition, paragraph 5.3, “The Incident Commander shall have overall authority for management of the incident (5.3.1) and the Incident Commander shall ensure that adequate safety measures are in place (5.3.2).” This shall include overall responsibility for the safety and health of all personnel and for other persons operating within the incident management system. While the Incident Commander (IC) is in overall command at the scene, certain functions must be delegated to ensure adequate scene management is accomplished.2 According to NFPA 1500 Standard on Fire Department Occupational Safety and Health Program, 2007 Edition, “as incidents escalate in size and complexity, the Incident Commander shall divide the incident into tactical-level management units and assign an incident safety officer (ISO) to assess the incident scene for hazards or potential hazards (8.1.6).”4 These standards indicate that the IC is in overall command at the scene, but acknowledge that oversight of all operations is difficult. On-scene fire fighter health and safety is best preserved by delegating the function of safety and health oversight to the ISO. Additionally, the IC relies upon fire fighters and the ISO to relay feedback on fireground conditions in order to make timely, informed decisions regarding risk versus gain and offensive versus defensive operations. The safety of all personnel on the fireground is directly impacted by clear, concise, and timely communications among mutual aid fire departments, sector command, the ISO, and IC.

Chapter 6 of NFPA 1521, Standard for Fire Department Safety Officer, defines the role of the ISO at an incident scene and identifies duties such as: recon of the fireground and reporting pertinent information back to the Incident Commander; ensuring the department’s accountability system is in place and operational; monitoring radio transmissions and identifying barriers to effective communications; and ensuring established safety zones, collapse zones, hot zones, and other designated hazard areas are communicated to all members on scene.6 Larger fire departments may assign one or more full-time staff officers as safety officers who respond to working fires. In smaller departments, every officer should be prepared to function as the ISO when assigned by the IC. The presence of a safety officer does not diminish the responsibility of individual fire fighters and fire officers for safety. The ISO adds a higher level of attention and expertise to help the fire fighters and fire officers. The ISO must have particular expertise in analyzing safety hazards and must know the particular uses and limitations of protective equipment.3

The situation when the initial company officer arrived on scene demanded his immediate attention and he did not have a chance to formally transfer command. This delayed some traditional duties of the initial command, such as designating a safety officer.

Recommendation #5: Fire departments should ensure fire fighters are trained in the procedures for searching above the fire.

Discussion: As stated in Dunn’s Command and Control of Fires and Emergencies, “There are two warning signs that may precede flashover: heat mixed with smoke and rollover. When heat mixes with smoke, it forces a fire fighter to crouch down on his hands and knees. If you are forced down to the floor by intense heat, consider the possibility of flashover. As mentioned above, rollover presages flashover.”3 Whenever one of these danger signs exists, defensive search tactics must be used. Three defensive search tactics are as follows:

- At a door to a burning room that may flashover, fire fighters should check behind the door to the room and sweep the floor near the doorway. Fire fighters should not enter the room until a hoseline is in position.

- When there is a danger of flashover, fire fighters should not go beyond the “point of no return.” The point of no return is the maximum distance that a fully equipped fire fighter can crawl inside a superheated, smoke-filled room and still escape alive if a flashover occurs. The point of no return is approximately 5 feet inside a doorway or window.

- When searching from a ladder tip placed at a window, look for signs of rollover if one of the panes has been broken. If rollover is present, do not go through the window. Instead, crouch below the heat and sweep the interior area below the windowsill with a tool. If a victim has collapsed there, you may be able to crouch below the heat and safely pull him to safety. 3

Fire fighters performing a search or interior attack should also be concerned with the danger of being trapped above a fire. This possibility is greatly influenced by the construction of the burning building. Of the five basic building construction types (fire resistive, noncombustible, ordinary construction, heavy timber, and wood-frame), the greatest danger to a fire fighter who must search above the fire is posed by wood frame construction. Vertical fire spread is more rapid in this type of structure. Flames may spread vertically and trap fire fighters searching above the fire in four ways: up the interior stairs, through windows, within concealed spaces, or up the combustible exterior siding.

During this incident, conditions changed very quickly in Apartment 2B and Apartment 3B. The fire had already been contained in Apartment 2B before the first crew entered through the Side A window. When the second rescue crew arrived and opened the front door, the door stayed open due to new carpeting that would not allow the code-required automatic door closure to work. This open door provided the oxygen the fire needed to flare up again and proceed to flashover in less than a minute. The stairwell to the third floor acted as a chimney that funneled all of the fire, smoke, and products of combustion through the open door where the victim was conducting his search. Within seconds, the rapid fire event forced the victim’s partner to bail out of the third-floor window on Side A and trapped the victim toward Side C of the structure. The intense heat compromised the victim’s facepiece. A staffed hoseline could have provided protection for the search crews and may have been able to control the rapid fire growth in the apartment the victim was searching. Fire-fighting and search activities commenced without first having a backup hoseline in place and operational.

Recommendation #6: Fire departments should ensure that fire fighters communicate interior conditions and progress reports to the incident commander.

Discussion: The size-up of interior conditions is just as important as exterior size-up. The IC monitors exterior conditions while the interior conditions are monitored and communicated to the IC as soon as possible. Knowing the location and the size of the fire inside the building lays the foundation for all subsequent operations. Interior conditions could change the IC’s strategy or tactic.7 Also, when operating inside the structure, fire fighters should communicate to the IC when making initial entry, searching and clearing areas, progressing between floors, and exiting the structure. During the initial stages of this incident, a command post was not set up at the front for arriving companies to report for assignment. Division “C” was with the hoseline inside the fire apartment and therefore not available at the rear of the structure to coordinate and assign arriving crews. Arriving companies were conducting suppression and search operations on their own initiative without any communications to the incident commander. Division “C” did not know that the fire had spread to Apartment 2B through the sliding glass door; therefore, it was not relayed to the incident commander.

Recommendation #7: Fire departments should ensure that interior search crews means of egress are protected by a staffed hoseline.

Discussion: Fire departments should develop standard operating procedures to ensure that a charged hoseline is either advanced with the search and rescue crew or is operated by another fire fighter, providing the team with protection while entering hazardous or potentially hazardous areas containing fire. A fire fighter is taking a substantial risk when entering a burning structure without a charged hoseline or protection from one. The only justification for risking a fire fighter’s life is when the location of an occupant is known by sight or sound to be within a few feet of the entry point to the structure or area on fire.8 According to Dunn, the most important fire-fighting operation at a structure fire is stretching the first-attack hoseline to the fire.3, 9 A properly positioned and functional fire-attack line saves the most lives during a fire.4 “It confines the fire and reduces property damage. Searches will proceed quickly, rescues will be accomplished under less threat, sufficient personnel will be available for laddering, ventilation will be effective, and overhaul above the fire room will be unimpeded.”9

In this incident, crews were making uncoordinated attacks simultaneously from Side A and Side C of the structure. The initial incident commander was attempting to complete his walk-around after being involved with the rescue of the civilian. Crews arrived and went to work on suppression and search activities without direction or coordination of the other crews.

The initial backup hoseline was being used to suppress fire through windows on Side A of the structure. The initial knockdown of the fire on the bottom floor gave a false sense of security that the scene was safe. The crews operating on the fireground had no idea that the fire had spread to Apartment 2B. Search activities were not coordinated through the incident commander or with any crews. In this incident, a hoseline inside the stairwell to protect the search crews means of egress may have extinguished the fire exiting the second floor and possibly prevented the flashover conditions while removing the civilian and limiting the possibility of fire traveling to the third floor.

Recommendation #8: Fire departments should ensure that staffed backup hoselines are utilized to protect the means of egress for the primary attack and search crews.

Discussion: Backup lines should not be used to attack fire in another area or for exposure control. Backup lines are deployed, charged, and on standby in the same general area of an attack line.10 In this incident, a backup line was pulled but was put into service through the front windows in an attempt to assist the initial attack crew with fire suppression at the front entrance. The backup line was not used to protect the initial attack crew and their means of egress in the stairwell. If a backup line had been in place in the stairwell, the fire may not have spread from the second floor to the third floor and may have provided a safe egress for the search crews.

Recommendation #9: Fire departments should ensure that truck companies announce the placement of egress ladders over the radio.

Discussion: Ground ladders can provide multiple emergency exits for fire fighters with victims and for fire fighters who are conducting interior searches. Ground ladders also provide additional exits when stairways become impassable. An officer in charge should announce over the radio the placement of ground ladders and their locations to be used as emergency eixts.11

In this incident, ground ladders were being deployed and then moved throughout the incident without any communication on where they were deployed. Announcing the placement of ground ladders for emergency egress allows the interior crews to know where possible paths of escape are located.

Recommendation #10: Fire departments should ensure that fire fighters are trained and retrained on Mayday competencies.

Discussion: Fire fighters need to understand that their personal protective equipment and SCBA do not provide unlimited protection. Fire fighters should be trained to stay low when advancing into a fire as extreme temperature differences may occur between the ceiling and floor. When confronted with an emergency situation, the best action to take may be immediate egress from the building or to a place of safe refuge (e.g., behind a closed door in an uninvolved compartment), call a Mayday, and manually activate the PASS device. A charged hoseline should always be available for a tactical withdrawal while continuing water application or as a lifeline to be followed to egress the building. Conditions can become untenable in a matter of seconds. In such cases, delay in egress and/or transmitting a Mayday message reduces the chance for a successful rescue.

Fire fighters should be 100% confident in their competency to declare a Mayday for themselves. Fire departments should ensure that all personnel who may enter an immediately-dangerous-to-life-and-health (IDLH) environment have training on Mayday competency throughout their active duty service. Presently, no national Mayday standards exist for fire fighters and most states do not have Mayday standards. Typically, a rapid intervention team (RIT) will not be activated until a Mayday is declared.4 Any delay in calling the Mayday reduces the window of survivability and also increases the risk to the RIT.12-17

The U.S. Fire Administration National Fire Academy has two courses on Mayday procedures: Q133 Firefighter Safety: Calling the Mayday, a self-study course, and H134 Calling the Mayday: Hands on Training; both courses are available on one CD, free of charge from the National Emergency Training Center publication office.14 The International Association of Fire Fighters also has a course that includes Mayday procedures, titled Fire Ground Survival.18

Any Mayday communication must contain the location of the fire fighter in as much detail as possible and, at a minimum, should include the division (floor) and quadrant. When in IDLH environments, fire fighters must know their location at all times to effectively give their location in the event of a Mayday. Once in distress, fire fighters must immediately declare a Mayday. The following example uses LUNAR (Location, Unit, Name, Assignment/Air, Resources needed) as a prompt: “Mayday, Mayday, Mayday, Division 1 Quadrant C, Engine 71, Smith, search/out of air/vomited, can’t find exit.” When in trouble, a fire fighter’s first action must be to declare the Mayday as accurately as possible and activate their PASS alarm.

Fire fighters also need to understand the psychological and physiological effects of the extreme level of stress encountered when they become lost, disoriented, injured, low on air, or trapped during rapid fire progression. Most fire-training curricula do not include a discussion of the psychological and physiological effects of extreme stress, such as encountered in an imminently life-threatening situation, nor do they address key survival skills necessary for effective response. Understanding the psychology and physiology involved in life-threatening situations is an essential step in developing appropriate responses. Reaction to the extreme stress of a life-threatening situation, such as being trapped, can result in sensory distortions and decreased cognitive processing capability.13 Fire fighters should never hesitate to declare a Mayday. There is a very narrow window of survivability in a burning, highly toxic building. Any delay declaring a Mayday reduces the chance for a successful rescue.19

In this incident, the victim called for a Mayday but did not manually activate his PASS alarm and gave an incorrect LUNAR. The personnel on the fireground did not know the locations of their search crews, and a RIT was not in place. The crews that were attempting to locate the victim were searching in Apartment 3A because the victim’s Mayday stated his location as the A/B corner of the third floor. All of these factored into the delay of reaching the victim. The fire department and incident command must ensure that Mayday transmissions are prioritized and acted upon immediately with the accountability of the crews working and an established RIT.

Recommendation #11: Fire departments should ensure that fire fighters and officers understand the capabilities and limitations of thermal imaging cameras (TIC) and that a TIC is used as part of the size-up process.

Discussion: Thermal imaging cameras (TICs) can be a useful tool for initial size-up and for locating the seat of a fire. Infrared thermal cameras can assist fire fighters in quickly getting crucial information about the location of the source (seat) of the fire from the exterior of the structure, which can help the incident command plan an effective and rapid response. Knowing the location of the most dangerous and hottest part of the fire may help fire fighters determine a safer approach and avoid exposure to structural damage in a building that might have otherwise been undetectable. A fire fighter about to enter a room filled with flames and smoke can use a TIC to assist in judging whether or not it will be safe from falling beams, walls, or other dangers. While TICs provide useful information to aid in locating the seat of a fire, they cannot be relied upon to assess the strength or safety of floors and ceilings.20 TICs should be used in a timely manner, and fire fighters should be properly trained in their use and be aware of their limitations.21, 22 While use of a TIC is important, research by Underwriters Laboratories has shown that there are significant limitations in the ability of these devices to detect temperature differences behind structural materials, such as the exterior finish of a building or outside compartment linings (walls, ceilings, and floors).23 Fire fighters and officers should be wary of relying on this technology alone and must integrate this data with other fire-behavior indicators to determine potential fire conditions. TICs may not provide adequate size-up information in all cases, but using one is preferred to not using one.

During this incident, the victim and his partner started a search without an assignment or briefing on the scene or building. Unknown to the victim and his partner, they ended up searching above the fire. A TIC may have decreased the time needed to search the apartment complex and could have assisted them in finding exit routes or safe havens, such as the sliding glass door or the kitchen.

Recommendation #12: Fire departments should ensure fire-fighting tactics do not increase hazards on the interior.

From an unknown breakdown in communication, Division “C” supervisor and his crew attacked the fire from Side C of the structure, which was the opposite way of the advancing attack line on Side A. The initial attack crew from Side A was forced from the entrance to the fire floor due to the intense fire conditions venting up the stairwell. The fire was too intense for them to reach the fire apartment. Interior fire attack should be a coordinated event. Hose streams operating from different sides of the structure may inadvertently push the fire in the direction of other crews.24, 25

Recommendation #13: Fireground tactics need to include effective ventilation to prevent fire spread.

Following an effective size-up, an essential component to assist in making fireground tactical decisions is to use Lloyd Layman’s RECEO VS (Rescue, Exposure, Confinement, Extinguishment, Overhaul and Ventilation, Salvage). Lloyd Layman was a pioneer in developing fire fighting tactics and wrote many books on the subject that are still the basis for many of today’s procedures. He served as the director of the Fire Office, Federal Civil Defense Administration, which was the first federal position having an advocacy responsibility to the nation’s fire service. He played a major role in preparing the Fire Safety and Research Act of 1968. He developed this acronym as part of his devoted work to fire-fighting tactics. The process is to prioritize the use of these tactics to effectively extinguish the fire and conserve property.

As mentioned, ventilation is not listed in order of implementation of the acronym, but must be considered to facilitate the completion of the fireground tactical goals. Ventilation is a great tool to assist with the following activities:

- Reduces danger to trapped occupants and allows for an increased rescue profile;

- Increases visibility for interior crews, which enhance their safety and effectiveness;

- Assist with rapid search and hose line advancement;

- Increases the speed at which the seat of the fire is located;

- Reduces the time required to find fire spread;

- Reduces the chances of flashover and/or backdraft;

- Positive pressure ventilation has the potential for moving fire and fire gases (only when windows and doors are maintained);26

It is very important to coordinate ventilation with interior attack crews and the Incident Commander. Without this coordination effort, the process becomes ineffective and can compromise fire fighter safety.

At this incident several factors influenced fire spread before ventilation by the truck companies could occur. These factors included the focus on the rescue of the occupant in Apartment 3A, the entry door to the fire apartment not being completely closed, the fire auto-extending into the 2nd Floor, and the fire being attacked from Side C.

Recommendation #14: Fire departments should ensure that a rapid intervention team (RIT) is established and available to immediately respond to emergency rescue incidents.

Discussion: At all fireground operations, a RIT should be designated and available to respond before interior attack operations begin.2, 5, 19 The RIT should report to the officer in command and remain in a designated ready position until an intervention is required to rescue a fire fighter(s) or civilians. The RIT should have all tools necessary to complete the task (e.g., search rope, first-aid kit, and resuscitator). The RIT’s only assignment should be to prepare for a rapid deployment to complete any emergency search or rescue when ordered by the IC. A RIT should preplan a rescue operation by finding out fire structure information (e.g., construction materials, layout, entry/egress routes), crew locations, and crew assignments and by monitoring radio traffic. When the RIT enters to perform a search and rescue, they should have full cylinders on their SCBAs and be physically prepared. When a RIT is used in an emergency situation, an additional RIT should be put into place in case an additional emergency situation arises.2

In this incident, E292 was the fourth-due engine, which is designated as the RIT by fire department procedures. While E292 was en route, the IC had proceeded to the rear of the structure to complete a size-up. He requested an engine company to the rear. Rather than report to the front as RIT, E292 reported to the rear of the structure, and the RIT assignment was not transferred to any other responding company. Due to the “Command” operating in “Limited Command” the RIT function was overlooked and not assigned to another company or “Command” calling the dispatcher and requesting additional resources to be assigned specifically as RIT.

Recommendation #15: Standard-setting organizations and authorities having jurisdiction should consider developing more comprehensive training requirements for fire behavior to be required in NFPA 1001 Standard for Fire Fighter Professional Qualifications and NFPA 1021 Standard for Fire Officer Professional Qualifications, and states, municipalities, and authorities having jurisdiction should ensure that fire fighters within their district are trained to these requirements.

Structural fires frequently display indicators and warning signs of rapid fire development—such as flashover, backdraft, and fire gas ignition—which many fire fighters and officers may not be sufficiently trained to recognize or understand. Fire fighters and officers must develop the understanding and skills necessary to identify and interpret the indicators so that they can anticipate the potential for extreme fire behavior and communicate their findings to the incident commander immediately.5, 24 This requires comprehensive training in fire behavior (theory) and practical application inclusive of realistic live-fire training.5, 27-29

NFPA 1001 Standard for Fire Fighter Professional Qualifications30 and NFPA 1021 Standard for Fire Officer Professional Qualifications31 were developed to ensure that fire fighters and officers have the skills necessary to perform their job. Currently, these qualifications do not include the need for a sound understanding of the physical, chemical, and thermal behavior of fire and do not make a connection between fire dynamics and the influence of tactical operations (positive pressure ventilation) and external factors (wind). Standard-setting agencies, states, municipalities, and authorities having jurisdiction should develop curriculum so that fire fighters and officers receive training on how to recognize and interpret fire behavior indicators and anticipate fire development.

The fire department involved in this incident incorporated a very proactive approach to training their fire fighters and officers to fire training requirements that meets or exceeds the current NFPA requirements including fire behavior training.

Recommendation #16: Research and standard-setting organizations should conduct research to more fully characterize the thermal performance of facepiece lens materials of self-contained breathing apparatus (SCBA) and components of other personal protective equipment (PPE) to ensure SCBA and PPE provide an appropriate level of protection.

Discussion: A number of recent NIOSH investigations, including this incident, suggests that the facepiece lens material may have melted before other components of the fire fighter’s self-contained breathing apparatus and personal protective equipment ensemble.32-35 Additionally, a number of documented near-miss incidents also identify the potential for thermal damage to facepiece lenses is greater than commonly believed.36-39