A Career Captain and an Engineer Die While Conducting a Primary Search at a Residential Structure Fire - California

Revised on April 16, 2009 to add information on the external review.

Revised on April 30, 2009 to clarify the Investigation Section and Recommendation #8.

Death in the Line of Duty…A summary of a NIOSH fire fighter fatality investigation

Death in the Line of Duty…A summary of a NIOSH fire fighter fatality investigation

F2007-28 Date Released: March 30, 2009

SUMMARY

On July 21, 2007, a 34-year-old career captain and a 37-year-old engineer (riding in the fire fighter position) died while conducting a primary search for two trapped civilians at a residential structure fire. The two victims were from the first arriving crew at 0150 hours. They made a fast attack and quickly knocked down the visible fire in the living room. They requested vertical ventilation, grabbed a thermal imaging camera, and made re-entry without a handline to search for the two residents known to be inside. Another crew entered without a handline and began a search for the two residents in the kitchen area. A positive pressure ventilation fan was set at the front door to increase visibility for the search teams. The crew found and was removing a civilian from the kitchen area as rollover was observed extending from the hallway into the living room. Additional crews arrived on-the-scene and started to perform various fireground activities before a battalion chief arrived and assumed Incident Command (IC). The IC arrived at 0201 hours and asked the victims’ engineer the location of his officer (Victim #2). The officer who assisted removing the civilian from the kitchen briefly re-entered to fight the fire. He then exited and notified the incident commander about his concern for the air supply of both victims who were still in the structure at approximately 0205 hours. Crews conducted a search for the victims and found them in a back bedroom where they had been overcome by a rapid fire event. Key contributing factors identified in this investigation include failure to report the fire by the alarm monitoring company; inadequate staffing; the failure to conduct a size-up and transfer incident command; conducting a search without protection from a hoseline; failure to deploy a back-up hoseline; inadequate ventilation and inadequate training on fire behavior. NIOSH investigators concluded that, to minimize the risk of similar occurrences, fire departments, municipalities, and private alarm companies should:

- ensure that fire and emergency alarm notification is enhanced to prevent delays in the alarm and response of emergency units

- ensure that adequate numbers of staff are available to immediately respond to emergency incidents

- ensure that interior search crews are protected by a staffed hose line

- ensure that firefighters understand the influence of positive pressure ventilation on fire behavior and can effectively apply ventilation tactics

- develop and implement standard operating procedures (S.O.P.’s) regarding the use of back-up hose lines to protect the primary attack crew from the hazards of deteriorating fire conditions

- develop and implement (S.O.P.’s) to ensure that incident command is properly established, transferred and maintained

- ensure that a Rapid Intervention Crew is established to respond to fire fighters in emergency situations

- implement joint training on response protocols with mutual aid departments

Additionally standard setting agencies, states, municipalities, and authorities having jurisdiction should:

- consider developing more comprehensive training requirements for fire behavior to be required in NFPA 1001 Standard for Fire Fighter Professional Qualifications and NFPA 1021 Standard for Fire Officer Professional Qualifications and states, municipalities, and authorities having jurisdiction should ensure that fire fighters within their district are trained to these requirements

INTRODUCTION

On July 21, 2007, a career captain and a career engineer (riding in the fire fighter position) died while conducting a primary search for two trapped civilians at a residential structure fire. On July 23, 2007, the International Association of Fire Fighters (IAFF) notified the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) of this incident. On July 27, 2007, the U.S. Fire Administration also notified NIOSH of this incident. On August 21-25, 2007 a Safety and Occupational Health Specialist, an Occupational Nurse Practitioner, and the Project Officer from the NIOSH Fire Fighter Fatality Investigation and Prevention Program investigated this incident. Meetings were conducted with the fire department and representatives of the IAFF. Interviews were conducted with fire fighters and officers who were involved with this incident, and the dispatch center. The investigators reviewed the victims’ training records, the department’s Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs), witness statements, dispatch logs, the victims’ personal protective equipment, death certificates, and autopsy reports. The incident site was visited and photographed.

FIRE DEPARTMENT

This career department consists of 344 uniformed fire fighters in 30 fire stations that serve a population of about 600,000 in a geographic area of approximately 304 square miles.

PERSONAL PROTECTIVE EQUIPMENT (PPE)

Both victims had a full ensemble of structural fire fighting protective clothing and gear meeting the applicable NFPA standards. The victims used Scott Life-Pak Fifty 4.5 Self Contained Breathing Apparatus (SCBA) which is equipped with integrated Pak-Alert SE Personal Alert Safety System (PASS) devices. They both had SCBA voice amplifiers and radios with lapel microphones.

TRAINING and EXPERIENCE

The State requires all career fire fighters to complete training equivalent to National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) Level I.

Victim #1 was an engineer with more than 8 years experience. He had more than 397 hours in basic Fire Fighter Level I training. He was on overtime and riding the fire fighter position for that shift.

Victim #2 was a captain with more than 10 years experience. He had received more than 480 hours in basic Fire Fighter Level I training.

STRUCTURE

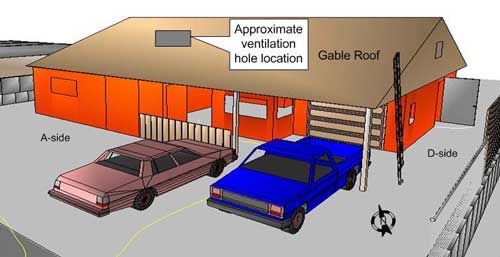

The residential structure was a single story, ranch-style, house made of wood frame construction with an exterior stucco finish that was built in the 1950’s. It was approximately 956 square feet (without garage) and had three bedrooms. All of the windows with exceptions to those on Side-A, had security bars attached to the outside. The original roof was constructed of full dimension sized 2-inch by 6-inch tongue-and-groove wood planks, laid flat and covered with built-up tar and gravel roof. A gable roof was added later over the original roof to provide better weather protection. It consisted of 2-inch by 8-inch rafters covered with plywood and asphalt shingles (Figure 1). This resulted in a void space between the two roofs that was used for storage by the residents.

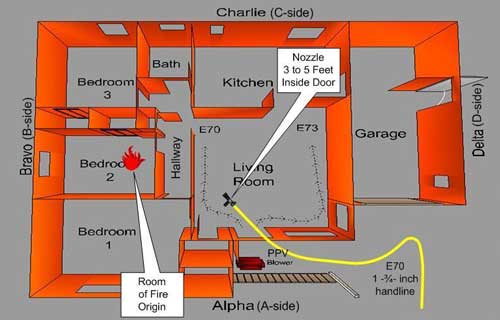

FIRE ORIGIN

The fire originated in the Bedroom 2 (see Figure 2) where the two victims were found. It is believed to have started from improper disposal of smoking materials by the owners.

WEATHER CONDITIONS

At the time of the incident, the conditions were clear with the temperature around 61 degrees Fahrenheit. The wind was between 2 and 6 miles per hour from the South to Southeast.

APPARATUS and STAFFING

Fire Alarm

| Resource Designation |

Staffing

|

On-Scene

|

|---|---|---|

|

Engine 70 (E70) |

Officer (Victim #2) |

0150 hours |

Structure Fire

| Resource Designation |

Staffing

|

On-Scene

|

|---|---|---|

|

Engine 73 (E73) Brush 473 |

Officer |

0151 hours |

|

Engine 69 (E69) |

Officer Engineer Fire Fighter |

0157 hours

|

|

Quint 76 (Q76)

|

Officer Engineer Fire Fighter |

0159 hours

|

|

Battalion Chief 7 (BC7)

|

Battalion Chief |

0201 hours

|

INVESTIGATION

On July 21, 2007, at approximately 0136 hours the central dispatch center received a call on their non-emergency line from a private security company to report a fire alarm from one of their residential customers. Note: Using a two-way intercom inside the residence, the alarm company representative had confirmed with the resident that there was a fire. This information was not reported to the fire department. The dispatcher placed the call on hold to answer higher priority (911) calls. Note: The report of a fire alarm has a lesser priority than the report of a fire. At 0142 hours the dispatcher took the call from the alarm company who confirmed that they have received a fire alarm from one of their customers, but the alarm company did not provide any further information on the incident. Note: The alarm company was calling from a call center that was located in a state on the east coast. The dispatcher attempted to call the residence, but was unsuccessful. At 0143 hours central dispatch, per their standard operating procedures, dispatched one engine, Engine 70 (E70), for a residential fire alarm and informed them there was no answer at the residence.

At 0145 hours the police department received a 911 call that they transferred to central dispatch. It was the female resident calling to report that their house was on fire and that her husband was still inside. At 0147 hours, central dispatch notified E70 that the call had been upgraded to a structure fire and that they were sending a full response. Note: The central dispatch center has an automated system that recommends units to be dispatched. It recommended an engine from an automatic aid department due to its proximity to the fire scene; however, Engine 73 (E73) that was located just a couple of streets away on a medical response, cleared their assignment and was able to respond immediately. Central dispatch was able to cancel the request for the automatic aid engine at 0149 hours. At 0150 hours E70 arrived on-the scene, established incident command (IC), and reported heavy smoke and fire from a residential structure. E73 arrived on-the-scene just seconds after E70 and was followed by a fire fighter/paramedic who was accompanying them with a Type-4 brush truck. The captain from E70, Victim #2, called central dispatch at 0151 hours and reported that they had two civilians trapped inside and were making entry with an inch and three-quarter handline (L1). As E70 was making entry the IC (E70 captain) passed command to E74. Note: The E73 crew was using an apparatus marked “E74” because E73 was out of service. The IC was observed looking at “E74” at the time he passed command. The officer on E73 did not hear the radio transmission and was unaware that Victim #2 had passed command.

The crew from E70 was at the front door and was on air as their handline was charged. The fire fighter from E73 met the crew at the front door just as they were making entry. Smoke and fire was pushing from the door and window on the front porch and the E73 fire fighter could see that the couch was on fire. Victim #1 was flowing water as Victim #2 called for the thermal imaging camera (TIC). The crew immediately knocked down the fire resulting in steam and white smoke pushing from the structure. Note: Due to the fast attack and the situation of trying to save the trapped civilians, the two victims were fighting the fire with water supplied from the engine’s tank. Victim #2 called central dispatch and requested rooftop ventilation at 0154 hours. Note: Central dispatch did not understand the transmission due to Victim #2 being on air and talking through his facepiece. Central dispatch had to confirm his request with Engine 69 (E69) while they were responding. The fire fighter from E73 went to retrieve the TIC. The E70 engineer told him that he would get it and directed him to help with hooking-up the hydrant. After assisting with the hydrant, the E73 fire fighter returned to make entry. The officer from E73 requested a positive pressure ventilation (PPV) fan from Engineer 70 because visibility was zero. The two victims were standing as they made entry through the smoke and proceeded to the left. The crew from E73 went to the right to search for the victims. The conditions were hot and visibility was near zero. (Figure 2).

E69 arrived on-the-scene at 0157 hours and proceeded to the front of the structure and met the engineer from E70. Note: While enroute, E69 noticed white/gray smoke from the fire area indicating a knockdown of the fire. The E69 officer noticed thick black/gray smoke pushing from the bedroom window on the A-side of the structure and heavy fire from the A/B–side of the structure. The E70 engineer conferred with the E69 officer about placing a PPV fan at the front door. The officer agreed and advised him to initiate the operation.

By the time the E73 crew made their way into the kitchen, approximately 25-feet, visibility had improved and they were able to see one of the civilian victims lying next to the refrigerator with the door open. They immediately began to remove the civilian and the conditions changed as fire started rolling over top of them. Note: When they were removing the civilian, they saw the nozzle approximately five feet inside the doorway. They got the civilian out to the front porch as the fire was rolling from the hallway area.

The crew from E69 laddered the D-side towards the front of the structure and then heard that the first civilian was found and was being removed from the structure (Figure 1). The E69 crew immediately went to the front porch to assist with removing the civilian to the front lawn area. Note: The gas powered PPV fan was running facing the front door. The E69 officer noticed that the smoke conditions in the living room area were negligible at this time.

Quint 76 (Q76) arrived on-the-scene at 0159 hours. While the crew was donning their gear, the Q76 fire fighter took a photograph and a short video that showed a rapid fire event venting from the A-side bedroom window (Photo 1). The E73 fire fighter was administering care to the civilian on the front lawn when the rapid fire event occurred and he reported large amounts of fire venting from the front bedroom window for approximately 15 seconds. Note: Members on the fire ground described the rapid fire progression as a sound resembling a tire exploding, which resulted in heavy flames shooting out from the front bedroom window.

The E69 crew had made their way back to the ladder on the D-side of the structure to access the roof. They cut a ventilation hole in the gable roof about two-thirds of the way over towards the B-side (Figure1). Initially there wasn’t any smoke or fire coming from the 6-foot by 6-foot ventilation hole. The E69 officer could see storage items in the attic as he attempted to knock out what he believed to be sheetrock or lathe and plaster ceiling with a pike pole to complete the vertical ventilation. Note: What the E69 officer thought was the ceiling was the original flat roof. The original flat roof consisted of actual sized 2-inch by 6-inch tongue-and-groove wood planks which was covered by layers of tar and gravel. The gable roof was placed over the original roof for added protection from the weather. He was unable to break open the original flat roof and the crew decided to exit the roof. While they were still on the roof the crew heard a loud “pop” and fire began to extend from the ventilation hole approximately 8 to 10 feet. The crew exited the roof and decided to ventilate the windows on the C-side of the structure.

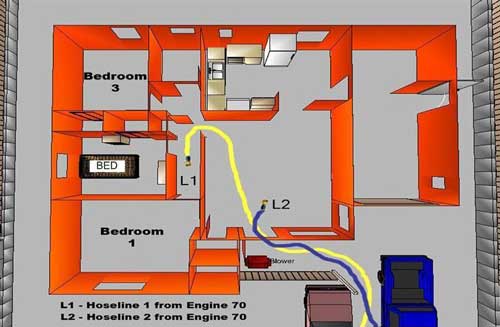

The E73 officer re-entered to fight the fire. The E73 officer started to fight the fire coming from the hallway area with the handline left by the victims just inside the structure when his low air alarm started to sound. The Q76 crew proceeded to the front of the structure and prepared to make entry. The E73 officer handed the handline to the Q76 crew who were making entry. Note: The Q76 crew had advanced a second 1 3/4-inch handline (L2) off of E70 to make entry. They put their handline on the floor just inside the door and advanced with the handline given to them by the E73 officer (L1) (Figure 3). Battalion Chief 7 (BC7) arrived on the scene at 0201 hours and assumed incident command. The E73 officer went to the BC7 to express his concerns regarding E70 crew’s air supply.

The Q76 officer was backing up his fire fighter on the nozzle as they fought fire around the corner and into the hallway leading into the bedrooms (Figure 3). They darkened down the fire in the middle bedroom and the captain scanned the area with his TIC and did not pick up anything on the screen. Note: The crew from Q76 did not know that the victims were missing at this point. The crew did not hear any PASS devices.

During this time, the Q76 crew had backed out of the middle bedroom and proceeded to the front bedroom where the fire was intensive. They knocked down the fire and proceeded to back out down the hallway. As they moved down the hallway heavy fire conditions began rolling overhead in the attic. The officer noticed fire in the attic area through a hole in the ceiling. He directed his fire fighter to flow water through the hole in an attempt to knock down the fire in the attic, but it had no affect on the fire. The officer and fire fighter were low on air and exited while their low-air alarms sounded. As they exited, they handed their TIC to the E69 crew who was just making entry after finishing horizontal ventilation.

The E69 crew was given an assignment by the BC7 to locate the second civilian after completing their ventilation mission at approximately 0203 hours. They entered with the TIC given to them by Q76 and experienced minimal smoke and heat conditions in the living room and kitchen areas. They found the second civilian, who had already passed away in the kitchen, and exited to inform the BC7 and request assistance with removal. During this time, BC7 attempted to locate the E70 crew on the fireground. He called central dispatch at 0205 hours and requested another alarm and informed them he had a fire fighter missing. Note: The automatic aid department that was cancelled earlier was included on the second alarm. When the E69 crew exited, BC7 informed them that he couldn’t find the E70 crew and directed them to re-enter and locate the missing fire fighters. Note: The tone and urgency of the request indicated to the crew that there was a problem.

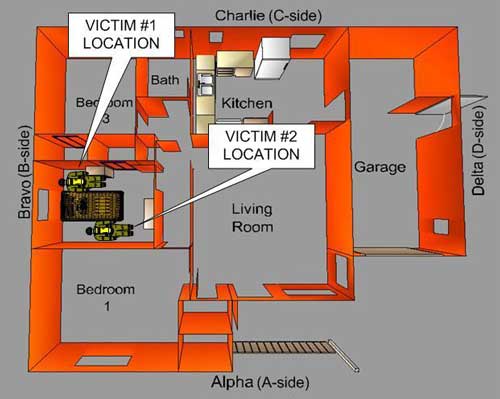

The E69 crew re-entered with a handline, but did not have a TIC with them. They proceeded into the hallway and bedroom areas and extinguished spot fires as they searched for the missing fire fighters and listened for any PASS devices. Note: It is probable that the PASS devices did not function properly due to the heat and fire impingement. The smoke was banked down to around neck level with good visibility below that level. The crew visibly searched the small bedrooms, but did not see the victims. The E69 officer exited to confirm his finding with the IC and to make sure the E70 crew was not outside. He went back inside and met-up with his crew in Bedroom #2. The crew was searching when the evacuation horns sounded at approximately 0221 hours. BC7 ordered the evacuation signal to conduct a personnel accountability report (PAR). They began to exit when the E69 engineer noticed Victim #1 in the right rear corner of Bedroom #2. They immediately began to remove Victim #1. FF76 and E68 crew assisted with the removal. BC 64 was on-the-scene at this time and was aware of a fire fighter missing, but not fully aware of the search operations taking place. Victim #2 was located on the left side of Bedroom #2 by the Q76 officer. Additional crews, including an automatic aid crew and BC 64 assisted with recovering the victim from the structure at approximately 0228 hours (Figure #4).

A complete incident timeline is included as Appendix A.

CAUSE OF DEATH

The autopsy report listed the cause of death for Victim #1 and Victim #2 as thermal injuries and smoke inhalation.

CONTRIBUTING FACTORS

Occupational injuries and fatalities are often the result of one or more contributing factors or key events in a larger sequence of events that ultimately result in the injury or fatality. NIOSH investigators identified the following items as key contributing factors in this incident that ultimately led to the fatality:

- Failure by the alarm company to report a confirmed fire

- Inadequate staffing to effectively and safely respond to a structure fire

- The failure to conduct a size-up and transfer incident command

- Conducting a search without protection from a hoseline

- Failure to deploy a back-up hoseline

- Improper/inadequate ventilation

- Lack of comprehensive training on fire behavior

- Failure to initiate/deploy a Rapid Intervention Crew

RECOMMENDATIONS

Recommendation #1: Municipalities and private alarm companies should ensure that fire and emergency alarm notification is enhanced to prevent delays in the alarm and response of emergency units.

Discussion: There was a significant delay in alerting fire units to this residential fire. The first report of a fire was received by the private alarm company (located in another state) who called the residence and verified the fire alarm prior to reporting it to the local emergency communications center. The alarm company called the non-emergency line for the emergency communications center and reported an alarm at a local residence. Per the local communications center protocol, the report of an alarm has a lesser priority than a confirmed emergency such as a fire. The call was put on hold due to the large volume of emergency calls with a higher priority. This situation resulted in a processing time of over 7 minutes. There were additional staff available (2 dispatchers were asleep at the dispatch center during this period) at the communications center but they were not utilized until a second alarm was requested and only then was one of them awakened to assist.

Private alarm monitoring companies should be thoroughly trained to receive and redirect the emergency call to the appropriate agency in the quickest time possible. Private alarm companies must have staff who are trained to be able to verify an alarm signal at a residence and report it correctly to local fire department and/or emergency communications center under 90 seconds.1 Emergency communications centers need to develop SOP’s and/or SOG’s on procedures for increased call volume periods and matching resources with needs.

Recommendation #2: Fire departments should ensure that adequate numbers of staff are available to immediately respond to emergency incidents.

Discussion: NFPA 1710 Standard for the Organization and Deployment of Fire Suppression Operations, Emergency Medical Operations, and Special Operations to the Public by Career Fire Departments (2004 Edition) contains recommended guidelines for minimum staffing of career fire departments.2

NFPA 1710 § 5.2.2 (Staffing) states the following: “On-duty fire suppression personnel shall be comprised of the numbers necessary for fire-fighting performance relative to the expected fire-fighting conditions. These numbers shall be determined through task analyses that take the following factors into consideration:

- Life hazard to the populace protected

- Provisions of safe and effective fire-fighting performance conditions for the fire fighters

- Potential property loss

- Nature, configuration, hazards, and internal protection of the properties involved

- Types of fireground tactics and evolutions employed as standard procedure, type of apparatus used, and results expected to be obtained at the fire scene.”

The NFPA standard states that both engine and truck companies shall be staffed with a minimum of four on-duty personnel. The standard also states that in jurisdictions with tactical hazards, high hazard occupancies, high incident frequencies, geographical restrictions, or other pertinent factors identified by the authority having jurisdiction, these companies shall be staffed with a minimum of five or six on-duty members. Jurisdictions where fire companies deploy quint apparatus designed to operate as either an engine company or a ladder company should also follow these same staffing guidelines.

NFPA 1710 also states that the fire department’s fire suppression resources shall be deployed to provide for the arrival of an engine company within a 4-minute response time and/or the initial full alarm assignment within an 8-minute response time to 90 percent of the incidents. The initial full alarm assignment shall provide for the following:

- Establishment of incident command outside of the hazard area for the overall coordination and direction of the initial full alarm assignment. A minimum of one individual shall be dedicated to this task.

- Establishment of an uninterrupted water supply of a minimum 1520 L/min (400 gpm) for 30 minutes. Supply line(s) shall be maintained by an operator who shall ensure uninterrupted water flow application.

- Establishment of an effective water flow application rate of 1140 L/min (300 gpm) from two handlines, each of which shall have a minimum of 380 L/min (100 gpm). Each attack and backup line shall be operated by a minimum of two individuals to effectively and safely maintain the line.

- Provision of one support person for each attack and backup line deployed to provide hydrant hookup and to assist in line lays, utility control, and forcible entry.

- A minimum of one victim search and rescue team shall be part of the initial full alarm assignment. Each search and rescue team shall consist of a minimum of two individuals.

- A minimum of one ventilation team shall be part of the initial full alarm assignment. Each ventilation team shall consist of a minimum of two individuals.

- If an aerial device is used in operations, one person shall function as an aerial operator who shall maintain primary control of the aerial device at all times.

- Establishment of an Incident Rapid Intervention Crew (IRIC) that shall consist of a minimum of two properly equipped and trained individuals.

Due to staffing and manpower limitations within the department, the small size of the initial responding crews at this incident could not appropriately and safely respond to the necessary fireground operations–e.g. incident command, scene size-up, water supply, ventilation, search-and-rescue, and a staged Rapid Intervention Crew (RIC).

Recommendation # 3: Fire departments should ensure that interior search crews are protected by a staffed hose line.

Discussion: Fire departments should develop SOPs to ensure that a charged hoseline is either advanced with the search and rescue crew or is operated by another fire fighter providing the team with protection while entering hazardous or potentially hazardous areas containing fire. A fire fighter is taking a substantial risk when entering a burning structure without a charged hoseline or protection from one. The only justification for risking a fire fighter’s life is when the location of an occupant is known by sight or sound to be within a few feet of the entry point to the structure or area on fire.3 According to Dunn, the most important fire fighting operation at a structure fire is stretching the first attack hoseline to the fire. 4, 5 A properly positioned and functional fire attack line saves the most lives during a fire. 5 “It confines the fire and reduces property damage. Searches will proceed quickly, rescues will be accomplished under less threat, sufficient personnel will be available for laddering, ventilation will be effective, and overhaul above the fire room will be unimpeded.” 4

In this instance, the initial crew made a fast attack and darkened down the fire within just a few seconds using tank water. They then requested a thermal imaging camera to conduct a primary search for the two trapped civilians. The nozzle was left 3-5’ inside the front door (unstaffed), while two search crews searched deeper inside the structure. The initial knockdown was not sufficient to control the interior fire seated in a bedroom and while the crews were searching the interior, conditions deteriorated rapidly to a heavy fire involvement trapping two fire fighters. A staffed hoseline with the search team could have cooled the hot gas layer leading to the rollover noticed by the E73 crew as well as finding and attacking the seat of the fire. Cooling the hot gas layer would have interrupted, and likely delayed the development of extreme fire behavior that trapped the victims.

Recommendation #4: Ensure that firefighters understand the influence of positive pressure ventilation on fire behavior and can effectively apply ventilation tactics.

Discussion: It is critical that fire fighters understand the influence of ventilation on fire behavior and the fire environment. Increasing ventilation to a ventilation controlled fire will result in increased heat release rate and may result in extreme fire behavior such as ventilation induced flashover or backdraft. However, effective tactical ventilation coordinated with fire attack can significantly reduce the potential for extreme fire behavior and increase tenability. 6, 7

Positive pressure ventilation is an extremely powerful tool that can rapidly clear smoke filled areas of the building. However, if used without considering the influence of ventilation on fire behavior, it can cause extreme fire behavior even more quickly. The following criteria should be met for safe and effective use of positive pressure ventilation:7, 8

- Firefighters understand the use of PPV and are skilled in its use

- Victims or firefighters are not between the fire and the exhaust opening

- The required tools are available for creating exhaust openings

- Location and extent of the fire is known. This is not an absolute requirement, but influences the most appropriate location for the exhaust opening

- Ventilation is coordinated with fire attack. This requires communication with personnel at the outlet, inlet, interior working positions, and command.

- A charged hoseline is in place for fire control

- Backdraft conditions are not present

- Ventilation openings can be controlled and an adequate exhaust (preferably 2 to 3 times the size of the inlet) opening is provided

- Positive control of the blower (the ability to start and stop positive pressure immediately)

Safety and effectiveness of fireground operations can be improved if the following considerations are addressed in the selection and implementation of ventilation strategies and tactics: 8

- Base ventilation decision-making on an understanding of fire dynamics.

- Recognize and address the influence of both sides of the ventilation equation: Smoke and Air

- Anticipate the impact of unplanned ventilation due to fire effects

- Integrate fire control and ventilation strategies.

In this incident, positive pressure was applied at the door on Side-A with the only exhaust opening being the large window in the living room which had broken out prior to the arrival of the first company. This potentially placed the search teams between the fire (in the bedrooms and hallway) and the exhaust opening (in the living room). In addition, no fire control action was being taken during the search as the hoseline deployed by E70 was unstaffed. Application of positive pressure without an adequate opening (in this case the opening may have been marginally adequate, but in a non optimal location) results in increased air supply to the fire, turbulence, and mixing of hot smoke (fuel) and air which can result in a fire gas ignition or ventilation induced flashover. It is not recommended to initiate positive pressure ventilation after firefighters enter the building.8 If used post fire control, fire fighters should be withdrawn to a safe (uninvolved) area or out of the building while it is pressurized. If used in positive pressure attack, the building should be pressurized and the effectiveness of ventilation verified by observation prior to entry. 8

In an experiment conducted by NIST using a PPV fan in a furnished room fire, the fire reached its peak burning rate and the flow was forced away from the entrance (PPV location) 60 to 90 seconds after the fan was turned on. The fan also caused a 60% increase in the burning rate, which increases the heat release rate; however; the corridor temperatures were much cooler than comparable temperatures in a naturally ventilated experiment. This reinforces the importance of creating a ventilation opening as close to the seat of the fire a possible to allow the products of combustion to be released to the exterior of the structure so that advancing members will not get caught in between the PPV and the exhaust opening. From the NIST experiment with proper exhaust size and location, fire fighters advancing inside the structure should wait 60 to 120 seconds to allow the flows to stabilize before entering a structure.9

Recommendation # 5: Fire departments should ensure that staffed back-up hoselines are utilized to protect the means of egress for the primary attack and search crews.

Discussion: Back-up lines are not used to attack fire in another area or for exposure control. They are deployed, charged, and on stand-by in the same general area to back-up an attack line.10 In this incident a backup line was not pulled by the second in crew and there was no hose line protection beyond 3-5 feet inside the front door. Once the fire conditions intensified, there was no way to control the fire spread and allow fire fighters a safe egress path. If a back-up line had been in place, it is possible that the fire build up could have been controlled and egress for the fire fighters maintained even though the initial attack handline was not in operation.

Recommendation # 6: Fire departments should develop and implement (S.O.P.’s) to ensure that incident command is properly established, transferred and maintained.

Discussion: Among the most important duties of the first officer on the scene is conducting an initial size-up of the incident. This information lays the foundation for the entire operation. It determines the number of fire fighters and the amount of apparatus and equipment needed to control the blaze, assists in determining the most effective point of fire extinguishment attack, the most effective method of venting heat and smoke, and whether the attack should be offensive or defensive. 11

In this incident, due to the limited number of staff and the confirmed entrapments, the initial IC made a fast attack on the fire to attempt a rescue. He transferred command over the radio to the next arriving apparatus. The next arriving apparatus was an engine being used by another company because their engine, Engine 73, was out of service. The IC was observed looking at the next arriving engine, Engine 74, at the time he passed command. However, transfer of command was never established. Subsequent tasks, such as primary search, hose line advancement, and positive pressure ventilation were performed without coordination or direction, and without proper safeguards and precautions in place. Positive pressure ventilation requires good fireground discipline, coordination and tactics. 11

Recommendation #7: Fire departments should ensure that a Rapid Intervention Crew is established to respond to fire fighters in emergency situations.

Discussion: A rapid intervention crew (RIC) should be available for the rescue of members operating at emergency incidents. The team should report to the officer in command and remain at the command post until an intervention is required to rescue a fire fighter(s) or civilians. The RIC should have all tools necessary to complete the job (e.g., a search rope, first-aid kit, and a resuscitator) to use if a fire fighter becomes injured. Many fire fighters who die from smoke inhalation, from a flashover, or from being caught or trapped by fire actually become disoriented first. They are lost in smoke and their SCBAs run out of air, or they cannot find their way out through the smoke, become trapped, and then fire or smoke kills them. The primary contributing factor, however, is disorientation. The RIC’s only assignment should be to prepare for a rapid deployment to complete any emergency search or rescue when ordered by the IC. The RIC allows the suppression crews the opportunity to regroup and take a roll call instead of performing rescue operations. A RIC should preplan a rescue operation by finding out fire structure information (i.e., construction materials, layout, entry/egress routes, etc.), crew location and assignments, and monitor radio traffic. When the RIC enters to perform a search and rescue, they should have full cylinders on their SCBAs and be physically prepared. When a RIC is used in an emergency situation, an additional RIC should be put into place in case an additional emergency situation arises.12

In this incident, a rapid intervention crew was not in place to assist the two fire fighters once command realized they were missing. Crews were sent in to search for the missing fire fighters, but were not formally assigned as a Rapid Intervention Crew and were placed in service in an uncoordinated fashion to search and recover the fire fighters. The first arriving fire fighters engaged the fire and attempted to rescue the trapped civilian occupants. The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), Respiratory Protection Standard, 1910.134 13 commonly referred to as the “2-in-2 out” rule, and NFPA 1500 allow for fire fighters to enter an immediately dangerous to life and health (IDLH) atmosphere without the benefit of a rapid intervention crew when there is a reasonable belief that a life can be saved. In this incident, later arriving crews went to work at the task level with no formal RIC established.

Recommendation #8: Fire departments should implement joint training on response protocols with mutual aid departments.

Discussion: Mutual aid companies should train together and not wait until an incident occurs to attempt to integrate the participating departments into a functional team. Differences in equipment and procedures need to be identified and resolved before an emergency occurs when lives may be at stake. Procedures and protocols that are jointly developed, and have the support of the majority of participating departments, will greatly enhance overall safety and efficiency on the fireground. Once methods and procedures are agreed upon, training protocols must be developed and joint-training sessions conducted to relay appropriate information to all affected department members.14

Fire departments should develop and establish good working relationships with surrounding departments so that reciprocal assistance and mutual aid is readily available when emergency situations escalate beyond response capabilities. During this incident, the first responding mutual aid department was cancelled due to E73 being cleared from a call close to the incident. When the mutual aid companies arrived on the scene, there was little coordination and communication between the two departments which led to some operational confusion, although fire fighters from the mutual aid department played key roles in recovering the missing fire fighters. Coordination of fireground efforts would have been enhanced if protocol planning, communication procedures (such as radio frequency/channel selection), and training had taken place among mutual aid departments.

Recommendation #9: The National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) should consider developing more comprehensive training requirements for fire behavior to be required in NFPA 1001 Standard for Fire Fighter Professional Qualifications and NFPA 1021 Standard for Fire Officer Professional Qualifications and states, municipalities, and authorities having jurisdiction should ensure that fire fighters within their district are trained to these requirements.

Structural fires frequently display indicators and warning signs of rapid fire development such as flashover, backdraft, and fire gas ignition for which many fire fighters and officers may not been sufficiently trained to recognize or understand. It is imperative that fire fighters and officers develop the understanding and skills necessary to identify and interpret the indicators so that they can anticipate the potential for extreme fire behavior and communicate their findings to the incident commander immediately. 11, 15 This requires comprehensive training in fire behavior (theory) and practical application inclusive of realistic live fire training. 6, 11, 16

NFPA 1001 Standard for Fire Fighter Professional Qualifications 17and NFPA 1021 Standard for Fire Officer Professional Qualifications 18 were developed to ensure that fire fighters and officers had the skills necessary to perform their job. Currently these qualifications do not include the need for a sound understanding of the physical, chemical, and thermal behavior of fire and do not make a connection between fire dynamics and the influence of tactical operations (positive pressure ventilation) and external factors (wind). Standard setting agencies, states, municipalities, and authorities having jurisdiction should develop curriculum so that fire fighters and officers receive training on how to recognize and interpret fire behavior indicators and anticipate fire development. An example of a recognized course in fire behavior is the United States Fire Academy (USFA) course “Fire Behavior in a Single-Family Occupancy”. 19 The National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) also provide an annual fire conference which includes seminars and presentations that cover various aspects of fire dynamics.20

REFERENCES

- NFPA [2007]. NFPA 72: National fire alarm code. Quincy, MA: National Fire Protection Association.

- NFPA [2004]. NFPA 1710 Standard for the Organization and Deployment of Fire Suppression Operations, Emergency Medical Operations, and Special Operations to the Public by Career Fire Departments. 2004 Edition. Quincy, MA: National Fire Protection Association.

- Firetactics.com [2007]. Model SOP Standard operating procedurepdf iconexternal icon. http://www.firetactics.com/Model%20SOP%20Standard%20Operating%20Procedure.pdf Date accessed: Mar 2009

- Dunn V [1992]. Safety and Survival on the Fire Ground. Saddle Brook, NJ: Fire Engineering Books and Videos.

- Dunn v [1999]. Command and control of fires and Emergencies. Saddle Brook, NJ: Fire Engineering Books and Videos.

- Hartin E [2005]. Why compartment fire behavior training (CFBT) is importantexternal icon. http://www.firehouse.com/article/10510694/Why-is-Compartment-Fire-Behavior-Training-CFBT-Important Date accessed: Mar 2009 (Link Updated 1/8/2013)

- Svensson, S. [2000]. Fire ventilation. Karlstad, Sweden: Raddningsverket

- Garcia, K., Kaufman, R., Schelble, R. [2006]. Positive pressure attack for ventilation and firefighting. Tulsa, OK:Penn Well.

- NIST [2005]. Effect of positive pressure ventilation on a room fireexternal icon. http://fire.nist.gov/bfrlpubs/fire05/art018.html Date accessed: Mar 2009

- NFPA [2008]. Engine company fireground operations. Quincy, MA: National Fire Protection Association.

- International Fire Service Training Association [2008]. Essentials of fire fighting. 5th ed. Stillwater, OK: Oklahoma State University, Fire Protection Publications.

- NFPA [2007]. NFPA 1500: Standard on fire department occupational safety and health program. Quincy, MA: National Fire Protection Association.

- OSHA Respiratory Standardexternal icon1910.134(g)(4) [https://www.osha.gov/pls/oshaweb/owadisp.show_document?p_table=STANDARDS&p_id=12716]. Date accessed: September 2008.

- Sealy CL [2003]. Multi-company training: Part 1. Firehouse, February 2003 Issue.

- Firetactics.com [2007]. Rapid fire phenomenonpdf iconexternal icon. http://www.firetactics.com/RAPID%20FIRE%20PHENOMENA%202007.pdf Date accessed: Jan 2009

- Firetactics.com [1999]. Realistic live fire training to deal safely with flashover and backdraughtpdf iconexternal icon. Http://www.firetactics.com/RAPID%20FIRE%20PHENomena%202007.pdf Date accessed: Mar 2009

- NFPA [2008]. NFPA 1001: Standard for Firefighter Professional Qualifications. 2008 ed. Quincy, MA: National Fire Protection Association.

- NFPA [2008]. NFPA 1021: Standard for Fire Officer Professional Qualifications. 2003 ed. Quincy, MA: National Fire Protection Association.

- USFA [2009]. Fire Behavior in a Single-Family Occupancy. http://www.usfa.dhs.gov/applications/nfacsd/display.jsp?cc=F356 Date accessed: Feb 2009 (Link no longer available 1/8/2013)

- NIST [2009]. Building and Fire Research Annual Fire Conference. http://www.bfrl.nist.gov/info/fireconf/ Date accessed: Feb 2009 (Link no longer available 12/6/2012)

INVESTIGATOR INFORMATION

This incident was investigated by Jay Tarley, Safety and Occupational Health Specialist, Scott Jackson, Occupational Nurse Practitioner, and Timothy Merinar, General Engineer, Surveillance and Field Investigations Branch, Division of Safety Research, NIOSH. The primary author of this report was Jay Tarley. Stephen Miles assisted with writing the recommendations for this report. Expert technical review was provided by Battalion Chief Edward Hartin, Gresham Fire and Emergency Services. Battalion Chief Hartin also constructed the incident timeline, Appendix A.

ADDITIONAL INFORMATION

The County Fire Protection District conducted a separate investigation of this incident. Their investigation report will be available at: http://www.cccfpd.org/press/documents/MICHELE%20LODD%20REPORT%207.17.08.pdf (Link no longer available 1/8/2013)

NIST has produced a DVD set titled: Positive Pressure Ventilation Research: Videos & Reports by Stephen Kerber and Daniel Madrzykowski, April 2008. The set focuses on fire service PPV tactics to improve fire fighter safety.

photos and Diagrams

|

|

|

Figure 3. Hoseline locations from E70. |

|

|

Photo 1. Flames exiting window on A-Side from rapid fire development.

|

Appendix A

The following timeline was constructed by integrating data from the County Fire Protection District’s Report and estimations of time to complete tactical operations.

| Fire Behavior Indicators & Conditions |

Time

|

Response & Fireground Operations

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

0134 |

|

|||

|

|

0135

|

|

||

|

|

0136

|

|

||

|

|

0137

|

|

||

|

0138

|

|

|||

|

0139

|

|

|||

|

0140

|

|

|||

|

0141

|

|

|||

|

0142

|

|

|||

|

0143

|

|

|||

|

0144

|

|

|||

| The female occupant exited the house and called 911 on her cell phone to report the fire (observation by bystanders). |

0145

|

|

||

|

The female occupant reentered the house in an attempt to rescue her husband (observation by bystanders). |

0146

|

|

||

|

0147

|

|

|||

|

0148

|

|

|||

|

0149

|

|

|||

| E70 reports smoke showing from one block out. |

0150

|

|

||

| Smoke and flame showing from the door and living room window on Side-A. |

0151

|

|

||

| Smoke and flame pushing from the door and window, the couch in the living room was on fire (observed by E73 FF). |

0152

|

|

||

| Steam and light colored/white smoke showing from the building. |

0153

|

E70 advanced 3 to 5-feet into the living room and knocked down visible fire. E73 hand stretched a 5-inch supply line 200-feet to a hydrant. |

||

|

0154

|

|

|||

|

0155

|

|

|||

|

Heavy smoke showing from Side-B (observed by E73 FF returning from the hydrant). Just inside the door, the smoke was thick and temperature was high (observed by E73). |

0156

|

E73 officer directed E70 engineer to place a blower at the door on Side-A. E73 entered the residence and started a right hand search (without a hoseline). E73 engineer shut off the natural gas service, but was unable to shut off the electrical service. |

||

| Thick black/gray smoke pushing from the window of Bedroom 1 on Side-A and a large volume of fire from Side-B (observed by E69). |

0157

|

|

||

|

Temperature and visibility increase noticeably as E73 reaches the kitchen. Rollover extends from the hallway into the living room (observed by E73). Smoke conditions negligible in the living room (observed by E69). |

0158

|

E73 locates an unresponsive female victim in the kitchen and removes her to the doorway on Side-A. E73 officer briefly operated the nozzle of the initial hoseline (approximately 5-feet inside the doorway) to knock down the flames extending from the hallway into the living room. After retrieving his flashlight from the kitchen, the E73 officer moved the blower 90o to allow the victim to be removed from the porch. After the victim was removed the blower was repositioned. |

||

|

0159

|

|

|||

|

Bedroom window on Side-A, which had been cracked and venting smoke, failed suddenly (glass blew out onto the lawn) with a large volume of fire pushing from the window for 10-15 seconds. (Observed by E73 FF who was performing patient assessment on Side-A). Sudden increase in flaming combustion from the bedroom windows on Side-A and Side-B (captured on video by Q76 FF). Fire fighters reported that the rapid fire progress sounded like a tire exploding (possibly failure of the window on Side-A). |

0200

|

E73 officer reentered through the door on Side-A to attack the fire in the hallway using the hoseline originally deployed by E70 crew. The E70 engineer pulled a second 150-foot 1 3/4-inch hoseline to the door on Side-A. |

||

|

0201

|

Vertical ventilation being performed by E69 (observed by Q76). Q76 advanced the second 1 3/4-inch hoseline into the building. E73 officer exited with his low air alarm sounding after handing the initial hoseline off to Q76. E73 officer expressed concern to his fire fighter that E70 would be low on air as well. |

|||

|

0202

|

|

|||

|

Light smoke exited from the vertical ventilation opening and a small volume of flame was visible from the area of the gable vent on Side-B (observed by E69). Poor visibility and high temperature with flames at the ceiling (rollover) in the hallway with a large volume of fire in Bedrooms 1 and 2 (observed by Q76). |

0203

|

|

||

|

0204

|

E69 completed a 6-foot x 6-foot ventilation opening in the roof but was unable to breach the original roof/ceiling to vent the interior of the building. E73 officer reported to BC7 and asked about the status of E70, expressing concern that they would be out of air. BC7 again attempted to locate E70, asking other crews and via radio on the assigned tactical channel as well as unassigned channels. |

|||

|

0205

|

|

|||

| Following a loud “pop”, a large volume of fire began to push from the vertical ventilation opening with a flame length of 8-foot-10-foot (observed by E69). |

0206

|

|

||

|

0207

|

|

|||

|

0208

|

|

|||

| No significant release of smoke was observed from the windows on Side-C (observed by E69). |

0209

|

E69 attempted horizontal ventilation on Side-C, removing screens and breaking out several panes of glass. |

||

|

0210

|

|

|||

|

Flames visible from the window of Bedroom 2 and gable vent on Side-B (observed by E69). Flames observed in the attic through a small opening in the tongue and groove ceiling (observed by Q76). |

0211

|

Q76 applied water into the attic through a hole in the ceiling without significant effect. |

||

|

0212

|

Command (face-to-face) assigns E69 to continue primary search for the male occupant. Search is initiated by E69 fire fighter and engineer (officer is changing air cylinder). |

|||

|

0213

|

E69 relieves Q76 on the second 1 3/4-inch hoseline and extends the line towards the kitchen. Command assigns Q76 to search for E70 around the exterior of the building after replacing their air cylinders. |

|||

| Minimal heat and smoke in the living room and kitchen (observed by E69). |

0214

|

E69 locates the male occupant in the kitchen (deceased). Command advises E69 to defer removal of the body and to continue the search for E70. |

||

|

0215

|

E69 walks through the interior in an effort to locate E70 and used first 1 3/4-inch hoseline (now in the hallway) to knock down flames in the closet of Bedroom 2. |

|||

|

0216

|

E69 reports to Command that E70 is not inside the building. Command directs E69 to conduct another search. The tone & urgency in the IC’s voice indicates a problem. |

|||

|

Large volume of fire in the attic with flames extending 10-feet to 15-feet out of the Side-B gable vent (observed by Q76). Smoke in the hallway and bedrooms had banked down to approximately 3-feet from the ceiling, with good visibility below that level (observed by E69). |

0217

|

|

||

|

0218

|

|

|||

|

0219

|

|

|||

|

0220

|

|

|||

|

0221

|

|

|||

| Visibility on the interior decreased as the volume of smoke increased and level of the upper layer dropped (observed by E69). |

0222

|

E69 engineer located Victim #1 on the right side of the bed (facepiece on and low air alarm ringing slowly). E69 attempted to remove the casualty but was unable to do so due to low air and fatigue. Note: Bell was not heard until victim was moved supine. Command assigned Q76 to assist in the search for E70. |

||

|

0223

|

FF76 hears “bedroom” then locates Victim #1 in Bedroom #2. |

|||

| Flames increased on the wall between Bedrooms 1 and 2. |

0224

|

FF76 yells for assistance. Additional personnel including E68 officer assisted in removal of the fire fighter casualty to the living room and then to the yard on Side-A. |

||

|

0225

|

|

|||

|

0226

|

|

|||

|

0227

|

|

|||

|

0228

|

Victim #1 was removed from the residential structure. Initial medical assessment indicated that the member was deceased. |

|||

|

0229

|

|

|||

|

0230

|

BC64 and Q76 officer initiated a search for the second member of E70. |

|||

|

0231

|

|

|||

|

0232

|

Victim #2 was located in Bedroom 2 by the Q76 officer. BC64 and E72 operated the 1 3/4-inch hoseline that was in the hallway to control the remaining fire in Bedroom 2 and assisted with removing Victim #2. |

|||

|

0233

|

|

|||

|

0234

|

|

|||

|

0235

|

Male civilian victim was removed from the building and defensive firefighting operations initiated to extinguish the remaining fire. |

|

The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH), an institute within the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), is the federal agency responsible for conducting research and making recommendations for the prevention of work-related injury and illness. In fiscal year 1998, the Congress appropriated funds to NIOSH to conduct a fire fighter initiative. NIOSH initiated the Fire Fighter Fatality Investigation and Prevention Program to examine deaths of fire fighters in the line of duty so that fire departments, fire fighters, fire service organizations, safety experts and researchers could learn from these incidents. The primary goal of these investigations is for NIOSH to make recommendations to prevent similar occurrences. These NIOSH investigations are intended to reduce or prevent future fire fighter deaths and are completely separate from the rulemaking, enforcement and inspection activities of any other federal or state agency. Under its program, NIOSH investigators interview persons with knowledge of the incident and review available records to develop a description of the conditions and circumstances leading to the deaths in order to provide a context for the agency’s recommendations. The NIOSH summary of these conditions and circumstances in its reports is not intended as a legal statement of facts. This summary, as well as the conclusions and recommendations made by NIOSH, should not be used for the purpose of litigation or the adjudication of any claim. For further information, visit the program website at www.cdc.gov/niosh/fire or call toll free 1-800-CDC-INFO (1-800-232-4636).

|

This page was last updated on 03/27/09.

The clock symbol indicates known times taken from dispatch center recordings and response data. The times are rounded off to the nearest minute.

The clock symbol indicates known times taken from dispatch center recordings and response data. The times are rounded off to the nearest minute.