|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

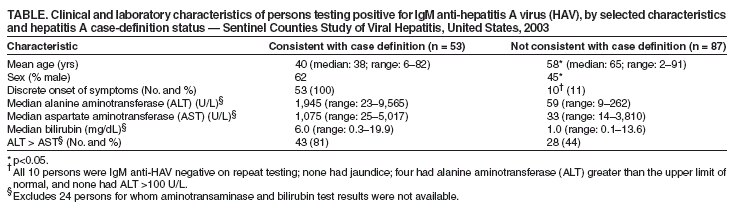

Persons using assistive technology might not be able to fully access information in this file. For assistance, please send e-mail to: mmwrq@cdc.gov. Type 508 Accommodation and the title of the report in the subject line of e-mail. Positive Test Results for Acute Hepatitis A Virus Infection Among Persons With No Recent History of Acute Hepatitis --- United States, 2002--2004Hepatitis A is a nationally reportable condition, and the surveillance case definition* includes both clinical criteria and serologic confirmation (1). State health departments and CDC have investigated persons with positive serologic tests for acute hepatitis A virus (HAV) infection (i.e., IgM anti-HAV) whose illness was not consistent with the clinical criteria of the hepatitis A case definition. Test results indicating acute HAV infection among persons who do not have clinical or epidemiologic features consistent with hepatitis A are a concern for state and local health departments because of the need to assess whether contacts need postexposure immunoprophylaxis. This report summarizes results of three such investigations, which suggested that most of the positive tests did not represent recent acute HAV infections. To improve the predictive value of a positive IgM anti-HAV test, clinicians should limit laboratory testing for acute HAV infection to persons with clinical findings typical of hepatitis A or to persons who have been exposed to settings where HAV transmission is suspected. ConnecticutThe Connecticut Department of Public Health investigated 127 IgM anti-HAV positive test results reported during January 2002--April 2003 via telephone interviews conducted with patients and health-care providers; 108 persons had illness consistent with the clinical and laboratory criteria of the CDC case definition for acute hepatitis A. The median age among these 108 persons was 41 years (range: 6--86 years); 60 (56%) were males. Among 19 persons who had illness that did not meet the case definition for hepatitis A, median age was 48 years (range: 28--88 years); 10 (53%) were females. None of the 19 persons reported recent exposure to a person with hepatitis A, and all either were asymptomatic (nine patients) or had a clinical presentation that was not consistent with hepatitis A (10). Three had elevated ALT concentrations (range: 61--300 units per liter [U/L]. Serologic testing for these persons was performed at one of eight clinical laboratories by using one of three licensed IgM anti-HAV test kits. No single brand of testing kit or lot number was used for all the tests. Three of the 19 persons had a previously reported positive IgM anti-HAV test result 4--59 months before the most recently reported test and did not have illness that met the case definition at the time of the previous report. Two patients had no record of having the test ordered, and the reason for testing was unknown for the remaining 17 patients. AlaskaA total of 27 cases of hepatitis A that were consistent with the CDC case definition were reported to the Alaska Division of Public Health during 2002--2004. Medical records of 10 additional persons who had positive tests for IgM anti-HAV reported but did not have illness consistent with the hepatitis A case definition were reviewed to identify the reason testing was conducted. The median age of these 10 patients was 60 years (range: 9--77 years). Seven persons had abnormal serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) concentrations, indicating likely liver injury or disease. However, six did not have an illness with acute onset and were considered unlikely to have hepatitis A. The seventh person had an illness with acute onset with elevated ALT but had acetaminophen toxicity diagnosed. The remaining three patients were asymptomatic; one had no written indication for testing, and two were tested to assess the need for, or response to, hepatitis A vaccination. Among these 10 persons, testing was conducted in one of four clinical laboratories by using one of three licensed test formats from one of two manufacturers. One person had been reported previously (in 2000) as having a positive IgM anti-HAV test result.† Sentinel Counties Study of Viral Hepatitis --- United States, 2003The Sentinel Counties Study is a population-based surveillance system conducted by CDC in six U.S. counties (Denver, Colorado; Jefferson, Alabama; Tacoma-Pierce, Washington; Pinellas, Florida; San Francisco, California; and Multnomah, Oregon); the overall age group and racial/ethnic composition in these counties is similar to that of the U.S. population (2). Reports of viral hepatitis are accepted from health-care providers and clinical laboratories. Health departments requested assistance in determining whether persons who tested IgM anti-HAV positive but did not have illness that met the clinical criteria for the case definition of hepatitis A had recent acute HAV infection. In response, CDC and the participating city and county health departments obtained epidemiologic and clinical data and either 1) the same diagnostic blood specimen previously collected for testing in the commercial laboratory or 2) a specimen drawn within 6 weeks of illness onset from all consenting persons reported in the surveillance areas during 2003 who had a positive IgM anti-HAV test result, regardless of whether they had illness consistent with the case definition for hepatitis A. Of 140 persons reported to have a positive IgM anti-HAV test result during 2003, a total of 87 (62%) did not have illness that met the case definition for hepatitis A or any other type of viral hepatitis, and 53 (38%) had illness consistent with the case definition. The 87 persons were not clustered in one county or in a single period; no more than seven were reported from any single county during a single month. Clinical laboratories, rather than health-care providers, were the sole source of the report for 50 (57%) of these persons, compared with 23 (43%) of those whose illness met the case definition (p<0.05). The 87 persons who did not have illness meeting the hepatitis A case definition were significantly older and more likely to be female (p<0.05), compared with persons whose illness was consistent with the case definition (Table). As expected, fewer persons who did not have illness meeting the case definition had discrete onset of symptoms or laboratory evidence of liver injury; however, because these criteria are included in the case definition for hepatitis A, tests of statistical significance for differences between the two groups were not performed. Of these 87 persons, 31 (36%) had sera available for repeat serologic testing at CDC. Of these 31 persons, two (6%) tested positive for IgM anti-HAV. One of 14 with ALT above the upper limit of normal (i.e., 30--50 U/L, depending on the clinical laboratory) was IgM anti-HAV positive on repeat testing. Of 25 specimens available from persons with no symptoms of HAV infection for HAV nucleic acid detection and sequence analysis, one (4%) specimen from a man aged 77 years had detectable HAV RNA, compared with 34 (66%) of 51 specimens from persons with both clinical and laboratory evidence of hepatitis A. On repeat testing of the same specimen, the man tested IgM anti-HAV negative. No hepatitis A cases were reported among contacts of persons whose illness did not meet the case definition. Reported by: ZF Dembek, PhD, JL Hadler, MD, Connecticut Dept of Public Health. L Castrodale, DVM, B Funk, MD, Alaska Div of Public Health. AE Fiore, MD, K Openo, MPH, K Boaz, MPH, T Vogt, PhD, P George, MPH, W Kuhnert, PhD, D Ricotta, MT (ASCP), O Nainan, PhD, IT Williams, PhD, BP Bell, MD, Div of Viral Hepatitis, National Center for Infectious Diseases, CDC. Editorial Note:Health departments have previously noted positive IgM anti-HAV tests among persons who do not have illness meeting the case definition for hepatitis A (CDC, unpublished data, 2001--2005); however, this report is the first to describe the clinical and epidemiologic characteristics of these persons. Findings in this report indicate that persons who are unlikely to have acute viral hepatitis should not be tested for IgM anti-HAV and that the use of IgM anti-HAV as a screening tool or as part of testing panels used in the workup of nonacute liver function abnormalities should be discouraged. Health departments should continue to apply clinical criteria in the case definition when conducting hepatitis A surveillance and determining whether postexposure immunoprophylaxis is needed for contacts. Postexposure immunoprophylaxis for contacts is unlikely to be indicated for persons whose illness does not meet the case definition, unless recent exposure to a person with acute HAV infection has occurred. A positive IgM anti-HAV test result in a person without typical symptoms of hepatitis A might indicate asymptomatic acute HAV infection, previous HAV infection with prolonged presence of IgM anti-HAV, or a false-positive test result. HAV infection can manifest a broad clinical spectrum, ranging from asymptomatic infection to typical hepatitis with fever and jaundice. Although an estimated 70% of children aged <6 years with HAV infection are asymptomatic, older children and adults usually have symptoms, and 70% are jaundiced (3,4). Studies conducted during hepatitis A outbreaks or among family members exposed to HAV indicate that HAV infection can cause asymptomatic infection with or without abnormal liver tests, primarily among young children (5). In Connecticut and Alaska, four persons had previously been reported with IgM anti-HAV positive test results. A prolonged presence of IgM anti-HAV after acute hepatitis A has been reported previously. In one study, IgM anti-HAV was observed in eight (14%) of 59 persons with hepatitis A for >200 days after onset (6); another study revealed that two of 15 patients with hepatitis A had detectable IgM anti-HAV >30 months after onset (7). HAV RNA can be detected for a mean of 79 days after the peak ALT and remains detectable in 40% of persons with acute hepatitis A for 70--127 days after the peak ALT (8). One person in the Sentinel Counties Study had detectable HAV RNA without recent symptoms of hepatitis. The finding that the same specimen was retested and determined to be negative for IgM anti-HAV suggests a false-positive HAV RNA (possibly from HAV RNA contamination of the clinical specimen), rather than acute asymptomatic HAV infection. HAV RNA tests are not yet licensed and will not provide results that are timely enough to help decisions about postexposure immunoprophylaxis. Although a prolonged positive test after a recent acute infection is a possible explanation for some persons with positive IgM anti-HAV but no recent signs or symptoms of hepatitis, most persons with positive anti-HAV test results in Connecticut, Alaska, and the Sentinel Counties Study were older adults without typical risk for infection, and most who were retested were determined to be IgM anti-HAV negative. None were reported to have transmitted infection to others. These data suggest that IgM anti-HAV positive tests in older persons without typical symptoms of hepatitis are more likely 1) false-positive test results or 2) the result of HAV infection that occurred months to years previously, rather than more recent HAV infection, which requires consideration of postexposure immunoprophylaxis for contacts. Testing of persons with no clinical symptoms of acute viral hepatitis, and among populations with a low prevalence of acute HAV infection, lowers the predictive value of the IgM anti-HAV test. Diagnostic tests for viral hepatitis, including licensed IgM anti-HAV tests, are highly sensitive and specific when used on specimens from persons with acute hepatitis. However, their use among persons without symptoms of hepatitis A can lead to IgM anti-HAV test results that are false positive for acute HAV infection or of no clinical importance. This might be occurring with use of laboratory test panels that include routine testing for IgM anti-HAV without requiring a specific order for the test (i.e., "reflex testing") among persons who are not being evaluated for possible acute hepatitis (e.g., persons with liver function test abnormalities or persons being screened for hepatitis C). The findings in this report are subject to at least two limitations. First, serum specimens from patients in Connecticut or Alaska who did not have illness meeting the case definition were not available for additional testing, and specimens were available from only 31 of 87 patients identified in the Sentinel Counties Study. Second, the reason for IgM anti-HAV testing for most patients whose illness did not meet the case definition was not available. Providing immune globulin is not recommended for contacts of IgM anti-HAV positive persons when the date that these persons might have been infectious is unknown (because no defined symptom onset is known), even for those patients who repeatedly test IgM anti-HAV positive. Clinicians and public health officials who receive reports of persons who are IgM anti-HAV positive in the absence of symptoms of viral hepatitis or history of recent contact with a hepatitis A patient should consider seeking additional information when making decisions about the need for postexposure immunoprophylaxis among contacts. Acute HAV infection is unlikely in persons who have received 1 or more doses of hepatitis A vaccine >1 month before symptom onset (3). Testing the patient for total anti-HAV and retesting for IgM anti-HAV might be helpful. Persons with acute HAV infection will test total anti-HAV positive; if the total anti-HAV test is negative, acute HAV infection is unlikely. Retesting the same or another serum specimen, preferably by using a different test format, might indicate that the person is IgM anti-HAV negative. Published guidelines for the workup of abnormal liver enzyme tests among asymptomatic patients do not include IgM anti-HAV testing (9). Health-care providers should limit use of IgM anti-HAV testing to persons with evidence of clinical hepatitis or to those who have had recent exposure to an HAV-infected person. Persons who are IgM anti-HAV positive but who do not have illness consistent with the case definition for hepatitis A should not be reported to CDC. References

* An acute illness with discrete onset of symptoms (e.g., fatigue, abdominal pain, loss of appetite, intermittent nausea, and vomiting) and jaundice or elevated serum aminotransferase levels. Confirmation requires serologic testing that demonstrates the presence of IgM antibody to hepatitis A virus (anti-HAV), or by identifying recent exposure to a confirmed hepatitis A case. † More detailed clinical and epidemiologic information for these cases is available at http://www.epi.hss.state.ak.us/bulletins/docs/b2005_03.pdf.

Table  Return to top.

Disclaimer All MMWR HTML versions of articles are electronic conversions from ASCII text into HTML. This conversion may have resulted in character translation or format errors in the HTML version. Users should not rely on this HTML document, but are referred to the electronic PDF version and/or the original MMWR paper copy for the official text, figures, and tables. An original paper copy of this issue can be obtained from the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office (GPO), Washington, DC 20402-9371; telephone: (202) 512-1800. Contact GPO for current prices. **Questions or messages regarding errors in formatting should be addressed to mmwrq@cdc.gov.Date last reviewed: 5/12/2005 |

|||||||||

|