|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

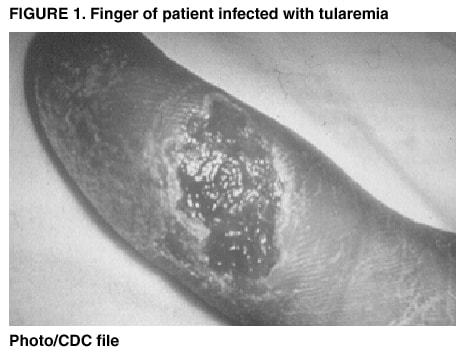

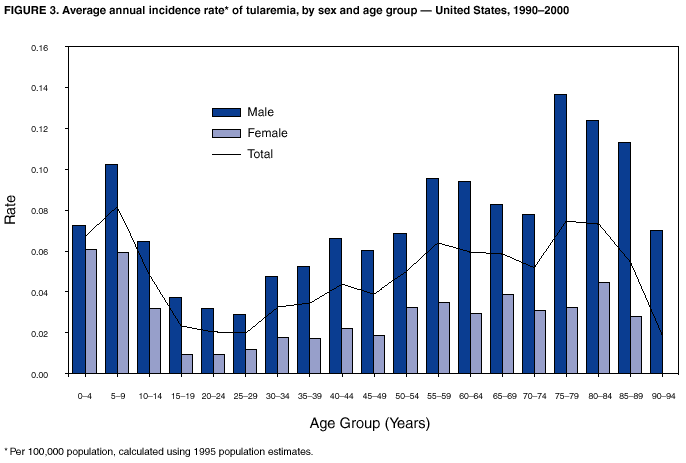

Persons using assistive technology might not be able to fully access information in this file. For assistance, please send e-mail to: mmwrq@cdc.gov. Type 508 Accommodation and the title of the report in the subject line of e-mail. Tularemia --- United States, 1990--2000Tularemia is a zoonotic disease caused by the gram-negative coccobacillus Francisella tularensis. Known also as "rabbit fever" and "deer fly fever," tularemia was first described in the United States in 1911 and has been reported from all states except Hawaii. Tularemia was removed from the list of nationally notifiable diseases in 1994, but increased concern about potential use of F. tularensis as a biological weapon led to its reinstatement in 2000. This report summarizes tularemia cases reported to CDC during 1990--2000, which indicate a low level of natural transmission. Understanding the epidemiology of tularemia in the United States enables clinicians and public health practitioners to recognize unusual patterns of disease occurrence that might signal an outbreak or a bioterrorism event. Tularemia characteristically presents as an acute febrile illness. Various clinical manifestations can occur depending on the route of infection and host response, including an ulcer at the site of cutaneous or mucous membrane inoculation (Figure 1), pharyngitis, ocular lesions, regional lymphadenopathy, and pneumonia. A diagnosis of tularemia can be laboratory-confirmed by culture of F. tularensis from clinical specimens or by a fourfold titer change of serum antibodies against F. tularensis. Presumptive diagnosis can be made by detecting F. tularensis antigens with fluorescent assays or by a single elevated antibody level (1). For purposes of national surveillance, confirmed and probable tularemia cases are defined as clinically compatible illness with confirmatory or presumptive laboratory evidence of F. tularensis infection, respectively. Before September 1996, because of ambiguity in the case definition, some cases of tularemia might have been considered confirmed by fluorescent assay alone. Case status is determined at the state level. For the purposes of this report, any case reported to CDC was assumed to have laboratory evidence of infection. Similar results were obtained when the analysis was limited to cases with documented confirmed or probable status. During 1990--2000, a total of 1,368 cases of tularemia were reported to CDC from 44 states, averaging 124 cases (range: 86--193) per year; 807 cases (59%) were reported as confirmed and 85 cases (6%) were reported as probable; the status of 476 cases is unknown. Most (91%) unclassified cases were reported during 1990--1992; all cases during 1990--1991 and 54% of cases from 1992 were not classified. The number of cases reported annually did not decrease substantially during the lapse in status as a notifiable disease during 1995--1999, but an increase in reporting occurred during 2000, when notifiable status was restored. Four states accounted for 56% of all reported tularemia cases: Arkansas (315 cases [23%]), Missouri (265 cases [19%]), South Dakota (96 cases [7%]), and Oklahoma (90 cases [7%]). County of residence was available for 1,357 reported cases. Among the 3,143 U.S. counties, 543 (17.3%) reported at least one case during 1990--2000. The counties with the highest number of reported cases were located throughout Arkansas and Missouri, in the eastern parts of Oklahoma and Kansas, in southern South Dakota and Montana, and in Dukes County, Massachusetts (the island of Martha's Vineyard) (Figure 2). During 1990--2000, the average annual incidence of tularemia reported using 1995 population estimates was highest in persons aged 5--9 years and in persons aged >75 years (Figure 3). Males had a higher incidence in all age categories. Incidence was highest among American Indians/Alaska Natives (0.5 per 100,000), compared with 0.04 per 100,000 among whites and <0.01 per 100,000 among blacks and Asians/Pacific Islanders. Of the 936 cases reported with date of onset, 654 cases (70%) reported onset during May--August, but cases were reported in all months of the year. Reported by: E Hayes, MD, S Marshall, MPH, D Dennis, MD, Div of Vector-borne Infectious Diseases, National Center for Infectious Diseases; K Feldman, DVM, EIS Officer, CDC. Editorial Note:The number of tularemia cases reported annually has decreased substantially since the first half of the 1900s. The incidence was highest in 1939, when 2,291 cases were reported (2) and remained high throughout the 1940s. The number of cases declined substantially in the 1950s and 1960s to the relatively constant number of cases reported since that time. In the United States, most persons with tularemia acquire the infection from arthropod bites, particularly tick bites, or from contact with infected mammals, particularly rabbits. Historically, most cases of tularemia occurred in summer, related to arthropod bites, and in winter, related to hunters coming into contact with infected rabbit carcasses. In recent years, a seasonal increase in incidence has occurred only in the late spring and summer months, when arthropod bites are most common. Outbreaks of tularemia in the United States have been associated with muskrat handling (3), tick bites (4,5), deerfly bites (6), and lawn mowing or cutting brush (7). Sporadic cases in the United States have been associated with contaminated drinking water (8) and various laboratory exposures (9). Outbreaks of pneumonic tularemia, particularly in low-incidence areas, should prompt consideration of bioterrorism (10). The high incidence of tularemia among males and among children aged <10 years might be associated with increased opportunity for exposure to infected ticks or animals, less use of personal protective measures against tick bites, or diagnostic or reporting bias. The high incidence among American Indians/Alaska Natives might be associated with their increased risk for exposure; outbreaks of tularemia have been reported on reservations in Montana and South Dakota, where a high prevalence of tularemia infection was found in ticks and dogs (4,5). The findings in this report are subject to several limitations, including underreporting and the lack of documented laboratory confirmation for all cases. Surveillance for tularemia could be improved by documenting laboratory confirmation of diagnosis and by including additional data (e.g., clinical presentation, exposure history, and outcome). Following a dramatic decline in the second half of the 20th century, the incidence of tularemia in the United States remains low. The epidemiologic characteristics described in this report provide a background against which unusual patterns of disease occurrence, including bioterrorism events, may be recognized more quickly. AcknowledgementThis report was based on data contributed by state and local health departments. References

Figure 1  Return to top. Figure 2  Return to top. Figure 3  Return to top.

Disclaimer All MMWR HTML versions of articles are electronic conversions from ASCII text into HTML. This conversion may have resulted in character translation or format errors in the HTML version. Users should not rely on this HTML document, but are referred to the electronic PDF version and/or the original MMWR paper copy for the official text, figures, and tables. An original paper copy of this issue can be obtained from the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office (GPO), Washington, DC 20402-9371; telephone: (202) 512-1800. Contact GPO for current prices. **Questions or messages regarding errors in formatting should be addressed to mmwrq@cdc.gov.Page converted: 3/7/2002 |

|||||||||

This page last reviewed 3/7/2002

|